Visa CEO Charlie Scharf: Moving at the speed of money

While overhyped cryptocurrencies like bitcoin grab all the attention, Visa CEO Charlie Scharf has quietly put a $6.8 trillion stranglehold on the world's commercial transactions. The future of payments? Surprise! It's already here

Sitting inconspicuously among the Pentagon contractors and trade associations in a western suburb of Washington, DC, is a low-slung building protected by landscaped berms and a fence topped by razor wire. The exterior walls are a patchwork of whites, greys and greens to confuse passersby trying to judge its size from a distance. A 24-foot-deep moat provides a last line of defence against anybody trying to crash a vehicle through its walls.

But while this fortress could easily pass as an outpost of some shadowy three-letter spy agency, it’s actually home to something far more mundane—and far more powerful. This is the nerve centre of Visa, the global credit card company. Walk through a biometric security scanner into its data centre—as I did recently—through a room dominated by huge video screens and past ranks of EMC data storage units holding petabytes of information ready for instant recall, and you’ll find a single IBM Z-class mainframe, like the black monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s science-fiction classic 2001, quietly crunching up to 100 billion computations every second. Almost every time somebody swipes a Visa card anywhere in the world, the transaction flows through here or a sister facility in Colorado. The company instantly checks 500 variables, from the customer’s location to his spending habits to the location of the merchant, and spits out a thumbs-up or -down on whether to allow the charge to go through. It’s the sort of centralised, big iron processing that Silicon Valley was supposed to obliterate years ago with peer-to-peer networks and cheap internet-connected devices.

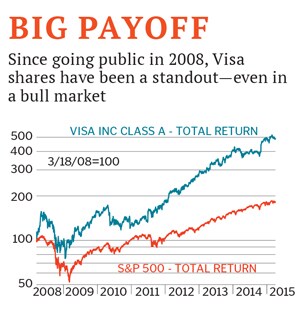

Yet Visa endures. And grows. The credit processing company, which started 57 years ago as a non-profit association of banks, went public on the eve of the financial crisis in 2008 and sailed through it with a 390 percent total shareholder return over the past six years, landing as No 263 on Forbes’s 2015 Global 2000 list of the world’s largest companies.

It is also one of the planet’s most prodigious cash machines. Visa had 60 percent operating profit margins on revenues of $12.7 billion last year and cash flow of more than $7 billion (dwarfing capital expenditures of $500 million). Visa handled 100 billion purchases worth $6.8 trillion, according to The Nilson Report, which tracks the credit card industry. That’s double the amount of rival MasterCard and 14 times that of American Express. For perspective, Visa thinks there are another $11 trillion in cash and cheque transactions in the world each year that could go electronic. And Visa’s transaction volume has been growing steadily at 10 percent a year since the IPO. Nonetheless, there are threats. Retailers have won billions of dollars in anti-trust suits accusing the company of helping banks keep fees—which can clip as much as 2.75 percent off a merchant’s revenue—too high. Customers love the easy credit but loathe interest rates that can top 20 percent. West Coast venture capitalists see Visa as an oligopolistic dinosaur and are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into rivals that use bitcoin. Meanwhile, banks, which collect the bulk of the fees from merchants, are warily eyeing Visa’s efforts to bypass them and forge direct relationships with retailers by offering one-click internet transactions and providing data on consumer behaviour that only Visa possesses.

None of which seems to faze Visa’s chief executive, Charlie Scharf. In time, he says, would-be Visa disruptors all discover—just as internet upstarts PayPal, Square and Uber did—that it is simply easier and more economical to work with his leviathan than fight it. “They don’t do what we do,” says Scharf, 50, who was a long-time lieutenant to JPMorgan Chase chief Jamie Dimon and took charge at Visa in 2012. “They don’t have the network we have.”

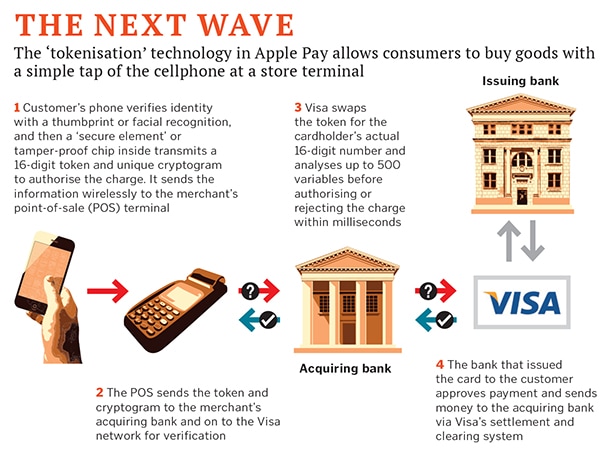

He’s already rushing to embrace what comes next: Providing the back end for smartphone-based payment systems such as Apple Pay and similar setups for Samsung and other mobile devices. Scharf’s technical team spent more than a year working with Apple before the launch of Apple Pay last October. The plan: Grab billions of dollars more in fees each year by making Visa the payment method of choice for everything—right down to $1 hamburgers at McDonald’s and three-block taxi rides in Singapore—with the ultimate goal of replacing cash itself.

“It took us 50 years to get to 36 million merchants globally,” says James McCarthy, executive vice president in charge of innovation and a former IBM executive who joined Visa in 1999. “Now,” he says, holding his iPhone in the air, “we’ve got 7 billion of these.”

Scharf interned at his father’s offices at Shearson Lehman Bros in New York from the age of 13 and landed a job as Jamie Dimon’s personal assistant during his senior year at Johns Hopkins. Instead of leaving for Wall Street after graduation in 1987, he joined Dimon at a Baltimore lending outfit known as Commercial Credit, run by an ambitious banker named Sanford I. “Sandy” Weill. For the next two decades, he accompanied Weill and Dimon on a journey through the evolving financial marketplace as Weill bought Shearson, Salomon Smith Barney, Travelers insurance and ultimately, in 1998, Citigroup.

After Dimon and Weill fell out in the late 1990s, in 2000, Scharf followed Dimon to Bank One in Chicago, where the two became closer (Scharf and his boss even shared a guitar instructor). He was named chief financial officer at 35 and then joined JPMorgan Chase as head of retail financial services, including mortgages, when it bought Bank One in 2004. Scharf guided JP Morgan’s retail and mortgage business through the financial crisis—the big bank took federal bailout funds only “because we were asked,” Dimon later said—but quit that job in 2011 to run JPMorgan’s $10 billion private equity arm. Dimon says Scharf came to him looking for a change after years in the same retail job. “What else could I do?” says Dimon, now JPMorgan Chase’s chairman and CEO.

He described his long-time lieutenant as “very diligent, very bright, very honest”, who has “an ability to handle lots of complex things, relate to lots of people”.

All of which is proving useful in Visa’s C-suite. The company has roots in BankAmericard, which San Francisco-based Bank of America rolled out in 1958 as the first credit card available to middle-class consumers and smaller merchants who lacked their own private charge cards.

Originally a simple paper card with a $300 credit limit, BankAmericard was vulnerable to fraud. Merchants literally flipped through telephone-book-size volumes to check the validity of card numbers. Bank of America spun out what became Visa in 1970, and three years later, Visa unveiled the first electronic authorisation system, called BASE I. It followed with BASE II in 1974, an electronic system for clearing and settling transactions among the banks that issue cards to consumers and “acquiring banks”, which represent merchants.

Now Visa sits at the centre of a global network of more than 1,500 banks linked by 1.5 million miles of secure fibre-optic lines, serving as a sort of intelligent switch for deciding whether to move money to pay for each transaction. It also scouts for fraud and helps settle disputes over charges. Visa doesn’t reap the reward of those usurious 20 percent interest fees or even the vast majority of the 2.75 percent charged to merchants. Instead it has to be content collecting 8 to 20 basis points, or hundredths of a percent, off of each transaction.

At the heart of the system is that 16-digit number embossed on the plastic bulging your wallet. When a customer swipes a card or cellphone at a merchant’s point-of-sale terminal, that information is transported to one of Visa’s data centres. Within milliseconds, its computers use a constantly evolving set of algorithms to determine whether the purchase fits the customer’s buying profile—or whether it’s likely to be fraudulent or exceed the bank’s credit limit.

But there’s a somewhat fatal flaw to all of this. With access to a credit card number, plus a few other easily obtainable details, fraudsters gain full control of an account’s purchasing power and can encode magnetic strips on blank plastic cards (Amazon.com will sell you a magnetic card reader/writer for $17). Worldwide, credit card fraud is estimated to have topped $14 billion last year, according to The Nilson Report, with banks and merchants bearing most of the cost.

To protect accounts, you need to keep those 16-digit numbers private, restricting access to those within Visa’s secure network. There are existing solutions: European card issuers have used difficult-to-copy microchips and personal identification numbers to protect transactions for years, but US merchants have resisted paying for the setup.

Systems like Apple Pay, which operate with software-based encryption known as “tokenisation,” promise an alternative, one with more security yet without the complication of punching a pin into a keyboard. Instead of using the customer’s actual 16-digit credit card number, a phone equipped with Apple Pay transmits a dummy number, a software “token”, as it’s known, which alerts the computer terminal at the retailer’s checkout counter to request another vital piece of information from a chip in the phone: A cryptogram, or a long string of randomly generated numbers, that only Visa’s computers can verify. Transactions can be further protected by biometric security like thumbprint scanners and even facial recognition. If a hacker somehow cloned a customer’s phone, Visa’s computers would detect that it was being used in two places at once and shut down the account.

“Tokenisation is the enabler,” says Scharf. “Whether they’re big tickets or small tickets, we like it all.”

Scharf joined Microsoft’s board last year, and he’s bingeing on talent like Rajat Taneja, 50, who once ran Microsoft’s ecommerce platform. Scharf recruited Taneja away from Electronic Arts in 2013 to run Visa’s sprawling technology division. Working out of Visa’s industrial-chic offices overlooking San Francisco Bay, Taneja will hire 2,000 software engineers and developers, including 1,000 in the US to create software and tools for online and mobile purchases this year, on top of the 6,000 employees he now oversees. He also oversees the once unthinkable process of opening up Visa’s network to outside developers working on the next generation of mobile apps. The company has already released a set of application programme interfaces, or APIS, to simplify transactions and speed the adoption of Visa Checkout, an encrypted, standardised version of Amazon’s one-click payment system for websites.

“We’re telling [developers], ‘Please dream, please build new applications’,” says Taneja.

Scharf recognises the potential threat from new electronic payment systems, most famously bitcoin, which replaces Visa’s sprawling computer network with a single registry maintained by many computers, where payments are transferred from one account to another with a simple journal entry. No one owns bitcoin; it’s just a platform created by an anonymous coding genius (or a group of geniuses) working under the name “Satoshi Nakamoto”. Venture capitalists, excited by the buzz around the new currency, have poured more than $300 million into businesses that enable bitcoin transactions or use its underlying currency. “I don’t stay awake at night worrying about bitcoin,” says Scharf.

Under Scharf, Visa is experimenting with alternative payment systems. It was an early investor in Square, which allows small merchants to process card transactions on their cellphones. Visa also reportedly put a few million dollars into LoopPay, which developed an ingenious method for generating a wireless version of a credit card’s magnetic strip. Within six months, Visa’s investment doubled in value, as Samsung scooped up LoopPay to install in its phones.

Now, Visa is working with automakers to embed tokenisation into cars, turning them, in essence, into rolling credit cards. Consumers will be able to query their onboard navigation system about the nearest pizza joint, order a large pie with bacon and onions, and pay for it in the drive-through via a secure bluetooth connection linked to the car’s unique vehicle identification number.

There’s another huge opportunity to all this technology, one the company is only starting to leverage: Personal data. Every time you swipe your card, Visa collects a tranche of information deep enough to drown an NSA agent: Spending habits, travel history and, with the addition of GPS-enabled devices, exact locations. The company knows more about the habits, hobbies, tastes and trends of the world’s consumers than any organisation on earth. “Visa has the most data—it’s the single-biggest advantage they have,” says Matt Harris, a managing director with Bain Ventures. Lately it has been tapping that vast trove of information to help member merchants. In 2011, Visa and clothing retailer Gap announced Mobile 4 U, for example, a service that allows Gap to fire text messages to consumers alerting them to deals when they are near a Gap store. Only Visa has all the data necessary to tell a retailer that a loyal, big-spending customer is nearby and possibly open to a discount offer, a potential gold mine for marketers. Of course, location-based marketing might strike some people as creepy, so Scharf says Visa will allow such programmes only on an opt-in basis.

Visa’s urge to help retailers isn’t totally altruistic: The company’s relationship with merchants remains strained, and Visa is looking to do more than just gin up additional transactions. Retailers have won billions of dollars in anti-trust suits against Visa and MasterCard, accusing them of helping banks keep fees too high with rules that prohibited them from encouraging customers to use cash or less expensive debit cards. As part of the settlement, Visa and MasterCard dropped those rules, but the two are still being sued by holdouts, including Walmart, which are seeking billions more.

“There is and there has been price competition in the business,” says Scharf. “People have choices.”

Perhaps the biggest problem for Visa is one that’s been part of the company since it was formed: Visa doesn’t issue Visa cards, and that’s unlikely to change anytime soon. “They don’t have any direct relationships with cardholders or any direct physical relationships with merchants,” says Harris.

Which means Visa can’t charge higher fees for providing rewards to consumers, say, or forge direct relationships with retailers unless it enlists an acquiring bank as an ally. Despite Scharf’s ambitions, he remains, ultimately, a vassal of the banks.

Scharf was forced to confront this weakness shortly after taking charge at Visa when JPMorgan Chase, the largest issuer of Visa cards, threatened to move its business to MasterCard unless Visa set up a private-label version of its processing network for the bank under a ten-year contract that reportedly includes lower fees. Scharf folded in this contest against his former boss, Dimon. Pressed to discuss Visa’s relationship with merchants and banks, Scharf says: “We understand who our clients are.”

For the time being, Scharf will have to remain content to boost revenue based on increasing the number of transactions it processes rather than increasing its cut. Visa’s greatest growth is likely to come in emerging markets, where cash dominates (and fees tend to be higher). China, so far, is off limits, with its $6.9 trillion credit card business held by the state-controlled UnionPay System, but Chinese officials plan to open up the processing side of the business to foreign companies.

Africa, too, represents a big opportunity. Developers there came up with a clever way to move money via prepaid cellphones, and Visa adapted its existing mechanism for paying refunds into a worldwide cash-transfer system.

Elsewhere in the developing world, Visa has used its analytics to help retailers identify bottlenecks, like the grocer in Indonesia who increased sales by accepting electronic payments for small transactions and thus sped customers through the checkout line.

Meanwhile, sales and earnings should climb steadily for some time. Deutsche Bank estimates Visa’s revenue will grow by another 11 percent next year to $15.4 billion as earnings per share, buoyed by a $5 billion stock buyback programme, rise 15 percent. At some point, Scharf will have to negotiate the purchase of Visa’s European operation, which is still owned by member banks, under a put option that could cost $10 billion, but for now, Visa gets fee income from Europe anyway. Besides, that’s just loose change to a company with ambitions as big as Visa’s. “The Visa story is not a two-year story or a five-year story,” Scharf says. “We have the opportunity to grow this company for decades to come.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)