Is India ready for home schooling?

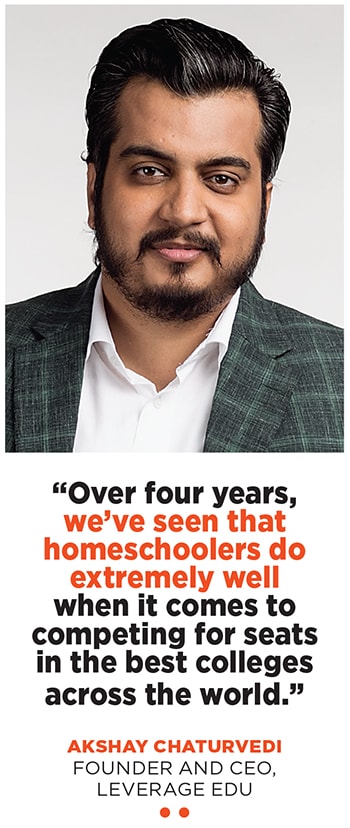

Concerns over a monotonous, formal education system coupled with edtech's innovative approaches bolster the homeschooling proposition over traditional schooling. But is India ready for it?

Amrutha Joshi Amdekar with her son Agastya (10) during a fun homeschooling session at their Mumbai residence

Amrutha Joshi Amdekar with her son Agastya (10) during a fun homeschooling session at their Mumbai residenceImage: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India

When Harshita Arora was introduced to computer science in Class 7 in 2015, she started exploring the subject beyond the specified CBSE syllabus. Her teachers at Pinewood School, Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh were supportive, and introduced her to coding even when the syllabus didn’t account for it. Curious to know more, she started researching and developed a passion for programming. “The internet was a relatively new concept for me. I’d come back from school and spend all my time trying to learn more about coding. It was fascinating to see this whole world of builders who were using their programming skills to build great companies,” she says.

By the time Arora was 15, she realised that she wanted to create an application, and that school was a constraint on the time she needed. “I knew what my goal was and that schooling wouldn’t help me achieve that. I started looking for alternatives online and was introduced to the concept of homeschooling,” she says. She started reaching out to parents who were homeschooling their children to know more about the possibilities.

Her parents, however, didn’t see it as a viable option. “They wanted me to complete school, go to college, and get a job like everyone else. They worried that if my plans for developing an application failed, it would be difficult to get admitted to colleges in India as homeschooling doesn’t have any legal status,” she explains. With Elon Musk as her role model, Arora was confident that the formal education system will only be a roadblock. After multiple discussions and introducing her parents to some successfully homeschooled children, they agreed.

With the internet as her teacher, Arora started homeschooling in 2016. A year later, she started developing a cryptocurrency tracker application to track prices of 1,000-plus cryptocurrencies from over 19 exchanges, and in January 2018 launched Crypto Price Tracker. “After a series of unexpected successes with the app, Redwood City Ventures acquired it in March 2018. That opened up an array of opportunities for me. I came to San Francisco and have since co-founded AtoB—a technology startup in the Bay Area.”

Arora is one of the select few children who achieved success by choosing a rather unconventional alternative to schooling. There are more like her. In 2010 and 2016, Sahal Kaushik and Malvika Joshi, two homeschooled children, came into the limelight when they were admitted to the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), respectively.

Supriya Joshi, Malvika’s mother, who started homeschooling her two daughters in 2003, is one of the pioneers of advocating homeschooling in India. She says initially her approach towards education was looked down upon; it was only after the academic success of her older daughter that people around her became curious about homeschooling, “It’s surprising to see how the success of homeschooling is more important to parents than understanding what it stands for,” says Joshi.

Homeschooling, an alternative approach to education, is a way of learning outside the defined parameters of school education and puts the parents/guardians in charge of their child’s all-round development. What and how to teach is determined by the parents who might not follow the curriculum of any education board. Parents either choose not to enrol their children in schools or—as is most prevalent in India—when a school’s approach doesn’t align with a child’s needs, they pull their children out of school.

Reliable research on homeschooling, its rising prevalence or outcomes is sparse. While there are no estimates of the number of homeschooled children in India, the cities of Mumbai, Pune, Bengaluru and Hyderabad seem to have most of the homeschooling communities.

Harshita Arora’s homeschooling helped her focus on coding, leading her to San Francisco where she co-founded a startup

Harshita Arora’s homeschooling helped her focus on coding, leading her to San Francisco where she co-founded a startupWhy Homeschool?

In India, the concept initially catered to specially-abled children who needed more parental support. But with the rise of concerns over a stringent education system, parents like Joshi started experimenting with the approach. Other reasons include concerns about bullying, child abuse, inefficient teaching practices and children wanting to build careers outside of academics.

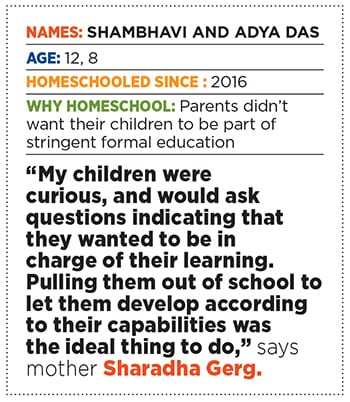

“I have questioned schooling since I was a child, but back then people didn’t pay heed to my concerns. The questions resurged when I had children; they were curious about the world around them, and we noticed that even after enrolling them in the best of schools, their emotional intelligence wasn’t being acknowledged,” says Sharadha Gerg (36), who has been homeschooling her two daughters since 2015. “My elder daughter would ask why she can’t study subjects in-depth… why does she have to stop after understanding the basics. These questions indicated that she wanted to be in charge of her own learning, and so pulling them out of school to let them develop according to their capabilities was the ideal thing to do.”

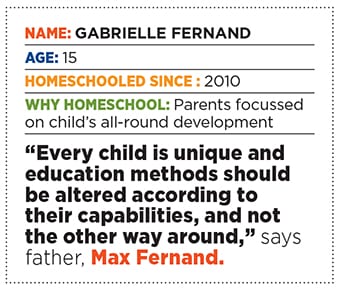

Max Fernand is another homeschooling parent in Mumbai who says schools do not acknowledge individual brilliance. “A typical classroom is filled with 60 students. One teacher cannot do justice to a room full of unique children,” he says. Having homeschooled both his children, Fernand highlights its perks. “My daughter reads history and science as per CBSE, mathematics as per US curriculum and English from another curriculum. So one can merge the best aspects of various curricula to suit a child’s aptitude.”

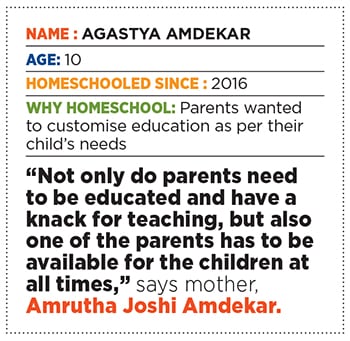

The Covid-19 pandemic has made parents more curious about homeschooling. “I get calls from a number of parents exploring homeschooling,” says Amrutha Joshi Amdekar, who has been homeschooling her 10-year-old son for the last four years. “I know a couple of parents who started homeschooling as a response to the increase in the time they could make for children. They started educating them by introducing several unexplored aspects of learning, which they were proud to post on social media,” she says, adding that as life goes back to normal, these parents might enrol their children in schools again.

Amdekar emphasises that homeschooling is a demanding “job” that needs an adult’s complete attention. “Not only do parents need to be educated and have a knack for teaching in a way that their kids understand, but also because one of the parents has to be available for the children at all times,” she says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

_20220316022208_102x77.jpg)