Watch Out for Counterfeit Goods

Yes, you can make money on art and collectibles. But so can forgers and thieves

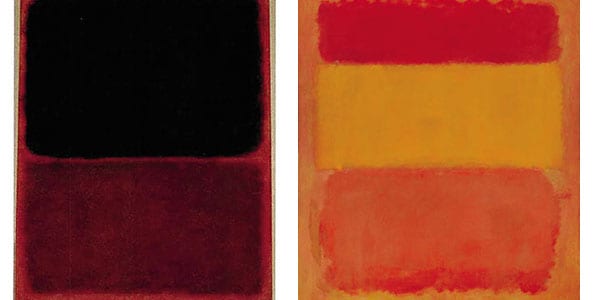

Photo / Christie’s Auction House (Right)

Can you distinguish the work of genius from its poor imitation? Hint: The red paint is a red flag. (The fake is on the left.)

When Domenico De Sole, who had recently retired as chief executive of Gucci, and his wife, Eleanore, visited the Knoedler Gallery in Manhattan in 2004, the gallery’s longtime president told them an intriguing tale about a Mark Rothko painting it had for sale. With the help of a now-deceased art dealer who knew Rothko, in the late 1950s a Swiss collector had purchased the 50-by-40-inch work, featuring two stacked rectangles painted in different mixes of red and black, directly from the artist. Now the collector had died, and his son was selling. While the son insisted on anonymity, Knoedler president Ann Freedman assured the De Soles that she knew him personally and that various experts, including a leading Rothko scholar and Rothko’s own son, Christo- pher, had authenticated the work.

The story was fiction and the painting a fake—or so the De Soles, who bought it for $8.3 million, allege in a lawsuit filed in federal court against Knoedler and Freedman. Theirs is just one of six suits brought by former patrons of the gallery, a respected part of the New York art scene for 165 years. These collectors claim that between 2000 and 2007 they paid millions for forgeries passed off as the works of abstract expressionists Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, among others. Knoedler closed abruptly at the end of 2011, shortly before Belgian hedge fund manager Pierre Lagrange brought the first suit—over a supposed Pollock he bought for $17 million.

The moral: Don’t worry just about buying on eBay. Even if you’re working with an established dealer or raising your paddle at a swank auction house, you can get stuck with counterfeit or stolen goods. Yet, too often buyers fail to take basic steps to protect themselves, lawyers and art experts say.

‘‘Sophisticated businesspeople would never do a business deal without asking questions, but somehow when they are buying art or collectibles, their common sense flies out of their head,” says Patty Gerstenblith, a professor at DePaul University College of Law and director of its Center for Art, Museum & Cultural Heritage Law.

Buying fine art and collectibles can sometimes pay off handsomely. According to ‘The Wealth Report 2013’ from Knight Frank, a London-based property firm, as a group, nine classes of collectibles, including classic cars, coins, stamps, fine art and fine wine, all outperformed equities in the decade ending September 30, 2012. The flip side of this is that thieves and forgers have more than ever to gain, too.

In May, Glafira Rosales, the Long Island art dealer who supplied the paintings to Knoedler, was charged with tax fraud for failing to report to the Internal Revenue Service and hiding in a Spanish bank at least $12.5 million from the sale of bogus works, which she falsely claimed had been owned by the deceased Swiss collector whose son was selling—much the same story Ann Freedman told Knoedler’s customers. While the charges only cover Rosales’ 2006-08 tax returns, the government alleges she has been passing off fakes since the late 1990s. She is being held without bail, and prosecutors say she’s a flight risk. Her lawyer did not reply to a request for comment.

Freedman, who was fired by Knoedler in 2009, now runs her own gallery. Despite the civil suits, she has not been charged by the government with any wrongdoing and sent this statement through her lawyer: “These paintings were exhibited in museums around the world and heralded as masterworks. The personal vendettas and professional jealously behind the attacks on the works and on my reputation should be obvious.”

Lawyers for the purchasers who claim to have been taken said their clients had no comment or did not respond to Forbes’ emails. Perhaps it’s not surprising that most wealthy collectors are reluctant to publicly discuss being duped.

Not all are reticent, however. William I Koch, the billionaire coal and petroleum magnate, has been on a nearly decade long legal crusade designed—or so he testified in federal court in April—to “shine a bright light on these fakers and the resellers of these fakes” in the collectible wine world. During that same testimony Koch described himself as “stupid” and “bloody naive” when he bought counterfeit trophy wine in 1988 and again in 2005.

The first time, Koch purchased four bottles that purportedly belonged to Thomas Jefferson. He discovered that fake in 2005 when he was asked to display one of his bottles at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and curators asked him to check the provenance. (For the record, the Forbes family was also famously duped in the Jefferson bottles scam.) Then, at an October 2005 Zachys auction, using a consultant as his buyer, he shelled out $3.7 million for 2,669 bottles of wine—a haul that turned out to include 24 fakes, one of them a 1921 Château Pétrus, for which he paid $29,500.

Koch became suspicious four months after the auction and ultimately brought in wine expert William Edgerton to inspect his collection. Coincidentally, Edgerton had been hired four years earlier by one-time-billionaire and serial entrepreneur Eric Greenberg and had singled out 108 bottles with questionable authenticity in Greenberg’s collection. Now two of the bottles with the labels Edgerton used to mark possible fakes had found their way into Koch’s collection via the Zachys auction, which consisted entirely of bottles consigned by Greenberg.

Greenberg offered a full refund of the $355,810 Koch paid for the 24 alleged duds. But Koch sued instead and finally tasted victory (his first, in his crusade) in April, when a Manhattan federal jury found he had been defrauded by Greenberg. It awarded Koch $12 million in punitive damages. Greenberg denies intentionally deceiving Koch and is seeking to have the award over-turned or reduced.

Koch’s punitive damages win is highly unusual. More often, neither judges nor juries show a lot of sympathy for collectors who get taken, Gerstenblith warns. “They think it’s one wealthy person defying another wealthy person,” she says.

Indeed, art and collectible buyers can’t routinely rely on any branch of government to protect them. Even if it did miss Bernie Madoff’s fraud, at least the Securities & Exchange Commission is supposed to watch out for stock investors.

So in the absence of a self-deputised sheriff like Koch, collectors are on their own. And hiring a “consultant” (as Koch had for his 2005 wine purchase) is no guarantee, particularly if that consultant’s compensation is tied to what you buy, reducing his or her incentive to squelch suspect purchases.

In fact, Lagrange, De Soles and Nicholas Taubman, the former US ambassador to Romania who sued Knoedler in May over an allegedly phony Clyford Still painting he bought for $4.3 million, had all retained art consultants to advise them. Those experts, like their clients, had simply relied on the gallery’s representations about the history of the paintings.

Taubman alleges Knoedler had a warning that something might be amiss. According to his suit, Jack Levy, former co-chairman of mergers and acquisitions at Goldman Sachs, wisely conditioned his own 2001 $2 million purchase from Knoedler of a supposed Pollock on a favourable review of its provenance and authenticity by the New York-based International Foundation for Art Research, an independent research service. Among other things, that organisation questioned the fact that the painting did not appear in Pollock’s catalogue raisonné. (That’s a comprehensive list of all the known works of an artist prepared by a recognised expert. A work that isn’t included in the catalogue may still be authentic but warrants special scrutiny.)

In 2003, Levy got a refund from Knoedler, which apparently procured the work for $750,000 from the now-in-custody Rosales. After repaying Levy, Knoedler officials, including Freedman, tried to show their faith in the work by investing in it personally.

Touching. Except there was more they could have done to investigate—such as calling in forensic experts. According to several of the suits against Knoedler, paint purported to have been used by Robert Motherwell, Still, Rothko and Pollock contained red pigment that was not commercially produced until several years after the dates on the paintings.

With collectibles there may also be experts and technology available to spot a fake. For rare coins you can consult the Professional Coin Grading Service or the Numismatic Guarantee Corp. The Professional Sports Authenticator evaluates baseball memorabilia—everything from cards to bats and uniforms.

Where there’s no independent third-party authenticator, ask a lot of questions, starting with, “Where did you get it?” Be especially careful on eBay, says Gregory J Rohan, president of Dallas-based Heritage Auctions, the world’s largest auctioneer of collectibles. An eBay regular, Rohan once shelled out for a counterfeit Paloma Picasso silver baby rattle on the site.

Ebay is also a source of mer-chandise for fraudsters. Irving Scheib of Bonsall, California, bought a 19th-century baseball glove on eBay for $750, made up a story that it was a family heirloom obtained directly from Babe Ruth—complete with provenance letters—and consigned it to a Nevada sports memorabilia broker for $200,000. The broker, in turn, sold it to a Long Island buyer, who asked Scheib to notarise the forged provenance letters. When Scheib refused, the buyer returned the glove, whereupon Scheib tried to sell it again—this time to an undercover US government investigator. In December, a Manhattan federal judge sentenced Scheib to two years of probation, during which time he is prohibited from selling memorabilia.

An eBay spokesperson declined to comment but referred Forbes to the company’s code of conduct, which prohibits selling counterfeits, and its buyer protection programme (a dispute resolution process that eBay hosts).

Traditional auction houses

perform their own due diligence, but it’s “unrealistic to expect them to be able to do extensive research” on each item, warns Jo Backer Laird, who spent 10 years as general counsel for Christie’s auction house before joining the law firm Patterson Belknap in New York. The auctioneers artfully limit their liability: The “terms and conditions of sale” in the back of a catalogue typically state the auction house only warrants the brief description of the item in boldface or italics, not all the other information printed. That limited warranty should cover the fact that a painting is indeed by a particular artist. The bigger problem: To enforce that warranty a buyer must generally sue within four years of a purchase, and many people don’t discover they’ve bought a fake until they go to sell the item or lend it to a museum. For fraud claims the clock starts to run only when you become, or should have become, aware of the fraud. Depending on the state, the statute of limitations may be as short as two years. And fraud is hard to prove.

By law, auction houses are also required to provide clear title. One source they check is The Art Loss Register, a service that lists 300,000 valuables owners have reported stolen. Individual buyers can check the register, too, for a $95 fee.

Problem is, not everything stolen is listed. Consider the dinosaur skeleton that was auctioned by Heritage last year.

According to documents in a federal court case quaintly titled United States of America v One Tyrannosaurus Bataar Skeleton, the man who consigned the museum-quality skeleton to Heritage indicated on customs documents that the country of origin for the 8-foot-high, 24-foot-long fossil was Great Britain, when, according to paleontologists, T bataar only lived in the Mongolian desert. The May 20, 2012, New York auction was interrupted by an announcement from a lawyer that his client, the president of Mongolia, had gotten a temporary restraining order from a Texas state court judge prohibiting the sale. Heritage went ahead with the auction but made the sale contingent on resolution of the court proceedings and has co-operated with the feds.

No money ever changed hands between Heritage and the victorious bidder—who was ready to spend $1.05 million to display the skeleton in the lobby of an office building that he owned, Rohan says. The consigner of the skeleton has pleaded guilty to helping to smuggle numerous dinosaur remains into the US and is out on $100,000 bail, awaiting sentencing.

As for the T bataar, he’s been repatriated to his homeland.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)