USA Colleges at Risk

Parents and students spend vast amounts of time and money trying to find a school that is the right fit academically and socially. They’d be wise to pay more attention to colleges’ financial health

In late June, nearly two months after most incoming freshmen had sent in their deposit cheques securing places at hundreds of colleges across America, Long Island University’s Post campus, nestled in the wealthy New York City suburb of Brookville, New York, was testing a new approach in its efforts to fill up the 250 or so empty seats it had in its class of 2017.

The week of June 24 was ‘Express Decision Week’ at LIU. High school seniors were invited to walk into Post’s Mullarkey Hall any time from 9 am to 7 pm, transcript, SAT scores and personal statement in hand, and LIU’s admissions officers promised to make an acceptance decision on the spot. All application fees would be waived, and registration for fall classes would be immediate. An identical event was being held simultaneously at LIU’s Brooklyn campus.

Post’s aggressive marketing ploy is eerily reminiscent of the on-the-spot low-doc-mortgage approvals that occurred during the heady days leading up to the housing crisis. But the product here is a bit less tangible than a loan that secures a house. These admissions officers are selling the promise of a better life through post-secondary-school learning.

LIU isn’t alone. Mount Saint Mary College in Newburgh, New York and Centenary College in Hackettstown, New Jersey offer similar same-day, on-the-spot admissions events. According to Jackie Nealon, Long Island University’s vice president of enrolment, LIU takes it a step further in the spring and sends admissions officers into Long Island high schools to admit students on location—the academic version of a house call.

If LIU sounds a bit desperate, it is. From a financial standpoint LIU is suffering from a host of ills common to hundreds of colleges today. According to the most recent financial data, LIU has supplied to the Department of Education, its Post campus has been running at an operating deficit for three years. Its core expenses, or those essential for education activities, have been greater than its core revenues. Like many other schools, Post is a tuition junkie, with nearly 90 percent of its core annual revenues derived from tuition and fees.

This year Post raised its tuition and fees by 3.5 percent to $34,005, yet it offers steep tuition discounts to nearly every incoming freshman. In fact, a quick click over to its website shows the deals available. If your kid is an A student with an SAT score of about 1300 out of 1600, expect at least a $20,000 rebate per year.

This seeming paradox of raising prices while simultaneously offering deep discounts is a way of life among middling and lower quality colleges in the market for higher education. It’s a symptom of a deeply troubled system where the cachet of elite institutions like Harvard and Yale has led thousands of non-elite schools to employ a strategy where higher prices and deeper discounts are more effective than cutting prices and tightening discounts. According to the National Association of College & University Business Officers, the so-called tuition discount rate has risen for the sixth straight year and is now averaging 45 percent. In some ways colleges oper- ate like prestige-seeking liquor brands. In other ways they are more like Macy’s offering regular sales days, only quietly.

LIU’s Post campus has a puny endowment of $43 million, or about $6,000 per each of its 7,000 enrolled students. (That compares to $2 million per student at Princeton.) Its admissions yield was last reported to be 17 percent—meaning fewer than two out of every 10 high school seniors it accepts choose to attend.

Of course, LIU’s precarious financial position says little about the quality of the education it offers—LIU doesn’t rank among Forbes Top Colleges but tends to fare well in rankings of regional schools. However, judged as an ongoing business, Long Island University would appear to be severely troubled, struggling year to year to pay its bills. Indeed, LIU recently hired a new president who is restructuring its operations.

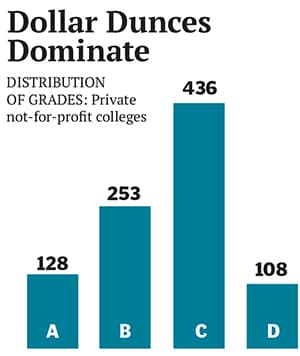

According to Forbes’s new Financial Grades, which analyses the balance sheets and operational strength of private not-for-profit colleges, Long Island University’s Post campus gets a grade of D.

LIU is by no means alone. Some 107 other schools earn a D—including well-regarded institutions like Ohio’s Wittenberg University—according to our analysis, and more than half of the 925 colleges we graded on financial fitness would be considered C students or worse (see ‘Behind the Grades’, p 85).

The prognosis is ominous in part because institutions of higher education operate in an extremely difficult business environment today. Imagine, if you will, running a company that sells a commodity product, where pricing is opaque and you have hundreds of competitors all clamouring after the same shrinking customer base—which, by the way, happens itself to be in financial distress.

Then consider that one of your other chief revenue drivers, subsidies and grants from federal and state governments, has either been cut back or eliminated. Add to this an evaporating competitive moat being stormed by newly minted for-profit businesses and cheap online alternatives.

“This environment is so competitive. Frankly, it’s a horror that we’ve largely inflicted on ourselves as a community,” says David Maxwell, president of Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, referring to the ongoing behind-the-scenes price/rebate wars. “In many ways it’s [a business] that’s dependent on the decision- making behaviour of 17-year-olds.”

Drake, which has an enrolment of 5,300 and was founded in 1881, faced insolvency a little more than a decade ago after most of its senior management had left. But after taking over in 1999, Maxwell cut expensive underenrolled programmes like graduate level nursing and redirected resources into high-demand offerings like its undergraduate pharmacy major. For the last eight years, Drake has shown small operating profits, and its endowment has grown to $169 million from $104 million in 1999. While Drake is still largely tuition-dependent, it earns a C+ for financial health among private colleges.

But managers like Maxwell are the exception. By far the biggest problem at most colleges is that they are governed in a way that flies in the face of sound business practices. The vast majority of colleges in the US are bloated with personnel and programmes that make little economic sense.

Almost all colleges have noble mission statements, but few have pervasive cultures or are able to focus employees on core competencies the way great companies like Coke, IBM and Wells Fargo do. Most colleges and universities try to be all things to all people.

“When I was CEO of a business, if we had a product that wasn’t selling, we took it of the shelf, and there was no question. We focussed on what the market demanded,” says Robert Dickeson, the former president of the University of Northern Colorado and author of Prioritizing Academic Programs and Services (John Wiley & Sons, 2010). “Higher education operates in a much different culture, and the decisions have usually been about serving more people and adding more programmes. Unfortunately, there hasn’t been a corresponding cutting of programmes or majors that no longer work. They operate this way out of a fear of having to cut people or some other dimension that isn’t rational.”

That way of doing business was tolerable when the market of high school graduates was expanding, as it was from 1990 to 2010. However, a study financed by the College Board and ACT shows that the production of high school graduates has fallen from its 3.4 million peak in 2011 to a current 3.2 million—and is likely to stay there until 2020. This ugly demographic fact, plus the decline in household wealth brought on by the Great Recession, has exacerbated the problem.

Amit Mrig, president of Denver research firm Academic Impressions, blames inept leadership across the board. “There is a denial bubble in higher education,” says Mrig, citing a study showing that 74 percent of college presidents state that their institutions cannot sustain additional budget cuts without negatively impacting quality.

University presidents must placate multiple factions outside of their boards of trustees, including faculty, and too often inaction is the easiest path. “One difference between the for-profit world and higher education is that you find numerous instances where the same people make the same budgeting and planning mistakes repeatedly and are not held accountable in any way,” says financial consultant Larry Goldstein of Campus Strategies in Crimora, Virginia.

When university presidents do step up and act more like corporate managers, they can face the kind of backlash R Owen Williams did at Kentucky’s Transylvania University. Williams cut his teeth on Wall Street over a 24-year career at Salomon Brothers, Goldman Sachs and finally as chairman of Bear Stearns Asia. After deciding on a career switch and earning a master’s degree in law and a PhD in history from Yale, he was hired in the summer of 2010 to run the Lexington, Kentucky liberal arts college. By most accounts Williams was succeeding. Enrolment had risen by 20 percent, and the 233-year-old school had begun construction of a new athletics complex.

However, in May 2013, Williams was socked with a “no confidence” vote from the college’s faculty. Apparently the professors didn’t like his no-nonsense approach to management and in a 35-page document described him as being “dismissive and disrespectful”. What really upset them was that Williams deferred a decision to award tenure to two professors.

Williams’s strategies had unanimous support from Transylvania’s board of trustees, and, according to Forbes’s financial health ratings, the small college earns a relatively impressive grade of A–. Nonetheless, Williams felt compelled to announce that he would resign after the 2013–14 academic year.

Some of higher education’s problems go beyond management. Even the metrics of higher education lead to inefficiencies. Today standard academic achievement, for example, is measured by credit hours, or ‘seat time’, which can run $1,300 per hour at schools like New York University. Undergraduates know that they need 120 credits to get a bachelor’s degree.

However, consultants like Dickeson argue that competency should be measured instead of hours. Online-only Western Governors University has been offering accelerated, self-paced degrees for 14 years. Last month the University of Wisconsin got approval from its regional accreditation organisation to offer similar competency-based degrees to undergraduates.

No one expects change to come rapidly to higher education. “A large number of institutions continue to operate in a triage mode,” says veteran college-bond issuer Fred Prager of investment banking firm Prager & Co. “They will remain reactive, with everything being a crisis. It’s very tough for them to pause and get even to a point of mendability.” That doesn’t mean consumers of higher education need to be in the dark. Combining Forbes’s Top College ratings with its new Financial Grades can help you home in on not just the best schools for the buck but also those that are likely to be around for many years to come.

Lucie Lapovsky, former VP of finance at Baltimore’s Goucher College and a higher-ed financial consultant, cautions against ignoring the financial health of the colleges you choose: “Visible signs of financial stress can include fewer classes offered less frequently, more classes taught by adjunct professors, less money for clubs and cutbacks in the upkeep of campus facilities.”

Financial woes are also the leading cause of accreditation suspensions. Indeed, more than a dozen schools among our C- and D- rated colleges are already facing some kind of accreditation inquiry. The last thing you want is for Junior’s college to lose its accreditation. When that happens the feds pull financial aid, enrolment plummets and the lights get turned out.

Behind the Grades

If colleges and universities were traded like stocks based on their listed tuition prices, higher education would be a short-seller’s paradise. College pricing is perversely inefficient—blue chips and penny stocks tend to be priced in the same narrow range. Except for a small number of elite institutions that don’t need to engage in discounting, listed tuition rates rarely represent actual fair values or real transaction prices. And they almost never reflect the underlying financial well-being of a college. To do that we created the Forbes College Financial Grades, which measure the fiscal soundness of more than 900 four-year, private, not-for-profit schools with more than 500 students (public schools are excluded). For the purposes of our analysis we used the two most recent fiscal years available from the Department of Education—2011 and 2010. The grades measure financial fitness as determined by nine components broken into three categories.

- Balance Sheet Health (40%): As determined by looking at endowment assets per full-time equivalent (15%), expendable assets (assets that can be sold in a pinch) to debt, otherwise known as a college’s viability ratio (10%) and a similar measure known as the primary reserve ratio (15%). Primary reserve measures how long a college could survive if it had to sell assets to cover its expenses. Schools like Pomona and Swarthmore are so asset-rich, for example, that they could cover expenses for 10 years without collecting a penny in tuition. Other well-known schools like Carnegie Mellon and Syracuse have primary ratios of about 1.0, meaning they could last about a year.

- Operational Soundness (35%): A blend of return on assets (10%), core operating margins (10%) and perhaps most important, tuition and fees as a percentage of core revenues (15%). Tuition dependency is the most serious risk facing middling colleges today.

- Admissions Yield (10%): The percentage of accepted students who choose to enroll tells not only how much demand there is from a specific school’s target customers but also gives an indication of the effectiveness of its admissions staff.

- Freshmen Receiving Institutional Grants (7.5%): The most desperate schools use ‘merit aid’ as a tool to lure more than 90% of incoming freshmen.

- Instructional Expenses per Full-Time Student (7.5%): Struggling schools tend to skimp in this area.

—MS

Schools of Deception

Some colleges will do anything to improve their ranking

By Abram Brown

Sometime in 2004, Richard C Vos, the admission dean at Claremont McKenna College, a highly regarded liberal arts school outside Los Angeles, developed a novel way to meet the school president’s demands to improve the quality of incoming classes. He would simply lie.

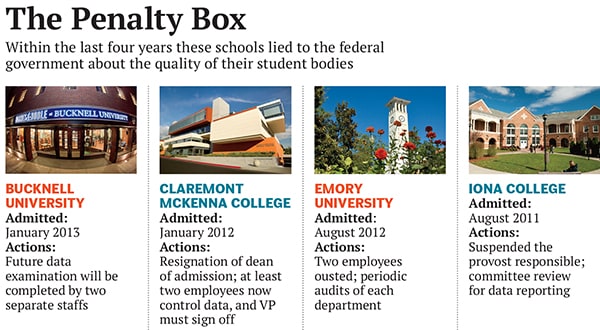

Over the next seven years, Vos provided falsified data—the numbers behind our ranking of Claremont McKenna in America’s Top Colleges— to the Education Department and others, artificially increasing SAT and ACT scores and lowering the admission rate, providing the illusion, if not the reality, that better students were coming to Claremont McKenna.

He got away with it thanks to a disturbing lack of oversight; he was trusted to hand-calculate the data and submit it without review. What had made this long-time employee break bad? “He felt the same pressure to deliver as any executive does,” Claremont McKenna spokesman Max Benavidez says. (Vos, who resigned in January 2012, couldn’t be reached for comment.)

Just as an analyst’s upgrade can spark a rally in a specific stock, a college’s move up the rankings usually results in a financial windfall.

“There’s institutional pressure at colleges to achieve at all levels, and that includes rankings,” says Troy Onink, a college planning expert and Forbes contributor, “It’s a hypercompetitive world for the best students and for that tuition revenue.”

Claremont McKenna isn’t the only top college that lied. Bucknell University doctored SAT results from 2006 to 2012; Emory University provided numbers for admitted students rather than enrolled ones for more than a decade; and Iona College lied about acceptance and graduation rates, SAT scores and alumni giving for nine years starting in 2002.

All have since fessed up and claim to have instituted better practices. As a penalty for their dishonesty—and an acknowledgment of the growing scope of the problem—we are removing the four institutions from our list of the country’s best schools for two years.

Are there other cheaters out there? If there are, they also will be taken off the list. Stay tuned. We will be watching.

For full list of THE America's Top Colleges click here

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)