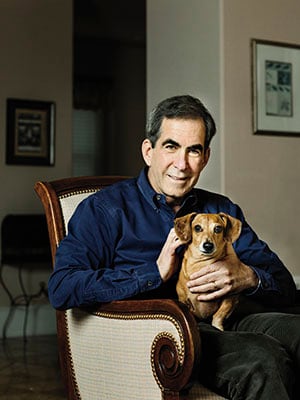

This Wall Street guy has your back

Allan Roth has an idea that could save you a bundle: Charging by the hour, rather than nicking a percentage of your assets

Allan Roth’s day job is mundane: He’s one of the country’s 285,000 (per Cerulli Associates) financial advisors. On the side, he’s a fanatic. He campaigns against the forces of darkness that lurk on Wall Street.

Roth has picked fights with: A former SEC enforcement director, a rulemaking group for municipal bond brokers, a disciplinary board that went too easy on a fee gouger and a professional journal that published a statistically bogus defence of active fund management.

He won no friends in his own profession by satirising its marketing (he had his dachshund apply for, and secure, a plaque awarded for being one of ‘America’s Top Financial Planners’). If in some hideaway the life insurance industry maintains an enemies list, Roth must be near the top, given his loud denunciations of indexed annuities, which offer the illusion of riskless participation in the stock market.

Quixotic? Yes, but these squabbles are worth understanding. They are part of a larger battle over who manages the nation’s personal savings ($7.4 trillion just in IRAs) and how those wealth managers get paid.

The US Department of Labor has just issued a controversial rule that requires advisors on retirement accounts to act like “fiduciaries” rather than salesmen. If it isn’t blocked by Congress, Wall Street will probably cope by doing more of what it has been doing anyway: Reduce its reliance on sales commissions and substitute an income stream from percentage annual fees. At Wealth Logic, Roth’s solo-manager shop in Colorado Springs, Colorado, there are neither commissions nor asset fees. His subversive theory is that money managers should charge by the hour.

In the past year, Roth estimates, he has advised 100 clients on a combined asset pool of $1 billion. A typical engagement has the clock ticking for between 10 and 25 hours, at $450 per hour. So a $10 million account might run up a $8,000 tab the first year.

After that clients may come back for smaller doses of help if their circumstances change. Or maybe they’re ready to maintain a portfolio on their own, with an ongoing management cost of $0. “The goal is for me to get fired,” says Roth.

Contrast this frugal style with the 0.6 percent to 1 percent annual fee that would be the norm elsewhere. On a $10 million account at either a giant brokerage or a boutique investment house, the investor would probably be paying at least $60,000. That doesn’t include the expense ratios embedded in the investment products chosen by the advisor. Include them and the cost might balloon to two or three times that $60,000, year in and year out.

Roth, 58, took up financial counselling 12 years ago after a career in corporate finance. He does no prospecting and no proselytising. Clients either come to him presold on the virtues of passive investing or they get turned away. They are spread across the country. A lot of them have never met him.

The first order of business is a financial plan spelling out allocations, safe spending levels in retirement, and advice on mortgages, pensions, estate plans, college savings and the conversion of pretax to aftertax IRAs.

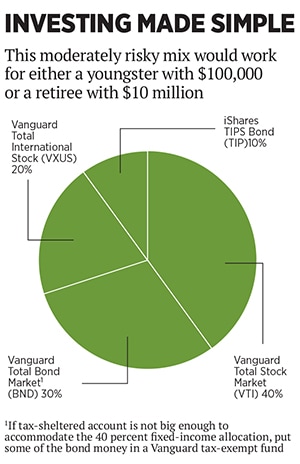

Then there is a cleaning of the stables. The objective is to replace messy and expensive investments with simple and cheap ones. The transition can be tricky. Do we want to get out of this overpriced stock fund badly enough to pay the capital gains taxes? What about that godawful annuity with the stiff exit fee if you leave too soon? “My business is the complexity of moving toward simplicity,” Roth says.

Most investment advisors would wince at this portfolio because it would be hard to justify a $60,000 fee for implementing it. And so they come up with things like the Endowment Fund, a complex fund of hedge funds with fees layered upon fees. During its heyday, Endowment was much favoured by financial advisors at Merrill Lynch. The fund disappointed, and people wanted out. But the operators invoked a clause permitting them to limit redemptions.

Roth got into a confrontation over this with Gary Lynch, the former head of enforcement for the Securities & Exchange Commission, now an executive with Merrill Lynch parent Bank of America. Roth thought Merrill should offer compensation to one of his clients. Lynch disagreed.

Roth lost that battle. (Merrill Lynch declines to comment.) You can learn from it. Hedge funds are just mutual funds with a few special features (stiff fees, low liquidity and murky disclosure). So buy mutual funds instead, he says.

Does your advisor have you in a collection of individual tax-exempt bonds? Be wary of that “income” number on your statement, Roth warns. You may have bought some premium-priced bonds that appear to be yielding 4 percent but are in fact delivering only half of that. The lower, honest number is called the “yield to worst”. It incorporates both the coupon income and the erosion of capital.

Using the inflated 4 percent number, a money manager can make a 1 percent annual fee look like it’s eating up only a fourth of your income. In truth it’s eating half.

Under an edict from the SEC, Lynch’s old agency, mutual funds are compelled to reveal the lower yield number. Roth has tried, in vain, to get the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board to extend this rule to brokers managing portfolios of individual bonds. There’s a lesson to draw from the dispute. Put your muni allocation in a Vanguard fund, where the fee is low (0.12 percent a year) and the correct yield number easy to find.

In olden times, stockbrokers, paid exclusively via sales commissions, could boost their income with excessive trading. The modern breed, getting paid by asset-based fees, has different temptations. Should you pay off your mortgage? Refuse a low-ball pension buyout? Delay social security? The asset-fee advisor might hesitate to answer yes, since each would reduce your investment assets subject to the percentage fee.

Whatever its merits, the hourly fee arrangement is a rarity today. Money managers are reluctant to give up the easy income that comes off a client with a large account and simple finances. Investors are reluctant to break off from an advisor who has served them for years. “Inertia is a powerful force,” says Roth.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)