The Wealth Wizards: Investment Tips from the Money Masters

We live in an era when immediacy and short-term thinking often trump the foundational wisdom that makes a difference in one’s financial life. Our 19 money masters share some timeless insights

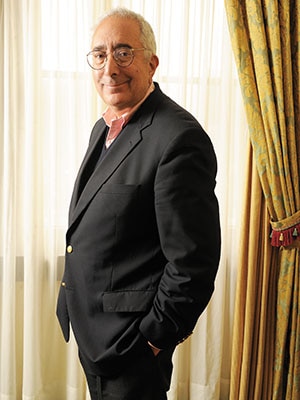

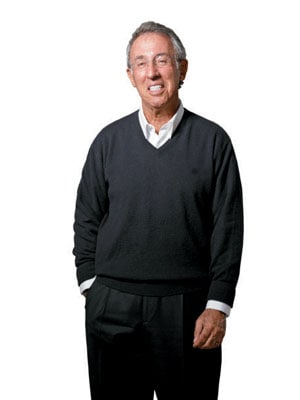

Ben Stein

Ben Stein

AUTHOR, ACTOR, FINANCIAL COMMENTATOR

In his latest book, How to Really Ruin Your Financial Life and Portfolio (Wiley, 2012), former game show host Ben Stein plays devil’s advocate by guiding readers into surefire ways to commit financial hara-kiri. “Pay No Attention at All to Taxes” is the title of Chapter 17.

But Stein’s contrary approach to financial advice belies a lifetime of financial smarts and wealth accumulation. For example, he still owns Berkshire Hathaway common stock he bought in 1983, when it sold for about $1,300 per share (it now trades for more than $171,000).

According to Stein, the best money advice he ever got came from his father, Herbert Stein, a Nixon Administration economist who lived his life with extreme financial prudence.

“I love real estate, but once, before I was about to buy an estate on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, my father warned me never to move into the neighbourhood of poverty,” says Stein, 68. Stein’s father wasn’t talking about this Chesapeake Bay enclave per se but was referring to taking on too much risk in any one deal. “It boils down to not having a meaningful amount of unsecured debt. It’s poison,” says Stein, who owns 12 homes.

As for getting rich, Stein advises to start young, buy stock index funds in the form of ETFs and reinvest the dividends. He also likes variable annuities, provided they are low cost.

“To me money in abundance is paradise and power and love. In scarcity it is terror and guilt.”

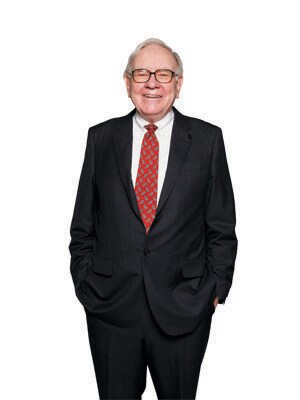

CEO, BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY

Do you have enough cash yet? Warren Buffett, the third-richest person in the world, says that he had all the money he needed by age 25, when his net worth reached $200,000.

“Money has given me the independence to do what I love daily. Beyond that it has no real utility for me but enormous utility for others. That is why I’m giving it away,” says Buffett, 82.

Indeed, Warren Buffett has joined pal Bill Gates and 112 other billionaires in The Giving Pledge, a rarefied group that has committed to giving the bulk of their fortunes to charity. So far Buffett has dispensed with more than $17 billion.

When asked what the best money advice he ever got was, it’s no surprise that Buffett turned to his holy bible, The Intelligent Investor, written in 1949 by value god Benjamin Graham.

“Chapters 8 and 20 have been the bedrock of my investing activities for more than 60 years,” he says. “I suggest that all investors read those chapters and reread them every time the market has been especially strong or weak.”

Here’s the Twitter-generation version of what is contained in those two chapters:

Don’t let the mood swings of Mr Market coax you into speculating, selling in panic or trying to time the market.

Only after careful analysis of a company’s ongoing business and its prospects for future earnings should you consider buying it and then only if its current price incorporates a significant “margin of safety”.

It boils down to avoiding losses by owning only stocks selling well below your calculation of their fair or intrinsic value. After that, the key is to keep your emotions in check and be patient.

AUTHOR, BLOGGER

“The best money advice I ever got is, ironically, the worst money advice I ever got,” exclaims Ramit Sethi, 30, personal finance guru, blogger and author of the bestselling book I Will Teach You to Be Rich (Workman, 2009). “Stop spending money on lattes.”

Sethi tried to save money by trimming little expenses like coffee, but it was hard. “We feel guilty, we overspend like we overeat and we think, ‘Okay, this month I am going to cut back.’ ”

“This taught me that money is not about willpower. Willpower is a depleting resource. We should focus on setting up systems, automating behaviours we want to happen.”

Sethi’s self-help shtick involves getting twenty- and thirty-somethings—of whom he has 500,000 online followers—to put as much of their financial life on autopilot as possible, setting up automatic deductions for 401(k) [pension contribution] plans, student-loan repayments, credit card bills. He even came up with a way to force himself to go to the gym.

“I realised I needed to put my gym clothes right near the floor with the shoes right there, so when I got out of bed my feet hit the shoes. Once I did that, my gym attendance went up.”

If you want to get rich, don’t focus on the minutiae. “Instead, get five or 10 big wins right, and you won’t have to worry about lattes.” Here are three: Invest early, get your asset allocation right and, above all, negotiate your salary.

Images From top: Getty Images, David Yellen / Corbis

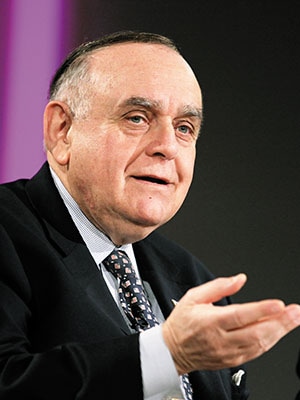

Leon Black

FOUNDER, APOLLO GLOBAL MANAGEMENT

Just before he graduated from Harvard Business School in 1975, private equity titan Leon Black’s father passed away, and he inherited $75,000 in life insurance money.

“I got involved trading commodities. I went into copper. I went into cattle, sugar, soybeans,” says Black, 61. “I’d never made this much money so quickly. At one point, I was up $600,000 to $700,000. I said ‘Boy, isn’t this a fabulous thing? This is fun, and this is easy!’ ”

Then prices plummeted, and for three days he was unable to sell. He lost all but $25,000 of his original capital. “There I was, a Harvard Business School graduate, and I lost two-thirds of my inheritance,” says Black. The money lessons were abundant. “Know what you are doing, avoid get-rich-quick schemes, do your homework, don’t bet the ranch,” says Black, now worth $4.3 billion. “I felt pretty silly.”

It’s impossible to overemphasise the importance of starting on the right track—Black worked early at Drexel Burnham Lambert with junk bond wizard Michael Milken. “Start your career in a place where there is a lot of action, a lot of smart people who understand risk and reward, and work hard. Learn to be patient, and learn to be opportunistic.”

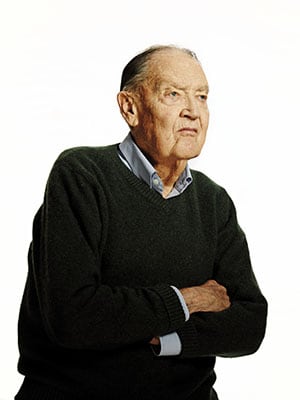

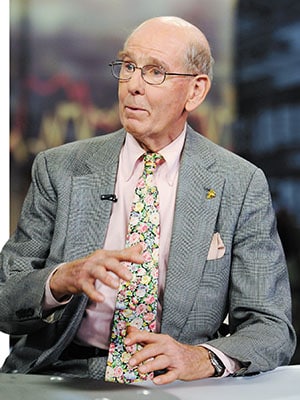

Burton Malkiel

ECONOMIST, RINCETON UNIVERSITY

“While there are some Warren Buffetts in the world,” says Princeton economist Burton Malkiel, “identifying one is like finding a needle in a haystack. I say buy the haystack.” Malkiel is referring to the get-rich-slowly strategy of regularly investing from a young age in a portfolio of broad, globally diversified stock index funds, easily accomplished using ETFs. “The only thing I’m absolutely 100 percent sure of is that the lower the fee I pay to the purveyor of the investment service, the more there is going to be for me. And that’s why index funds work.”

Still, the efficient-markets dean and author of the classic book A Random Walk Down Wall Street admits that his best investment return ever came from picking a single stock—precisely what he preaches against doing.

Says Malkiel, 80: “I had gotten out of the Army with $2,000, and my father told me to invest it.” Malkiel had been a finance officer and had worked on early IBM computers. Using a bit of what would later become known as Peter Lynch “buy what you know” stock picking, he put all $2,000 into IBM in 1958. “Today it’s worth almost $500,000,” he says, but is quick to add, “It was the wrong thing to do, because a friend at the time urged me to put the money into a blue-chip stock like Eastman Kodak. Had I done so I would have lost all my money.”

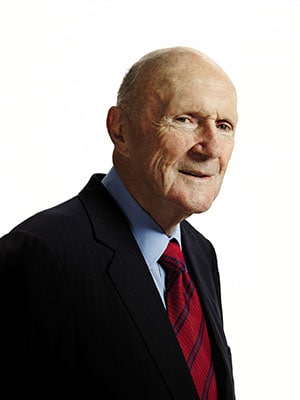

FOUNDER, OMEGA ADVISORS

“My dad would tell me there are more horses’ asses than there are horses,” says billionaire hedge fund manager Cooperman, 70. It’s the kind of advice that frames the sceptical “go against the crowd” mind of value investors like Cooperman. He likes out-of-favour stocks and ones that are underpriced relative to market multiples, book value and private market values. It works: His $8 billion Omega Advisors has been logging an average annual return of 13 percent since its inception in 1991.

Advice for getting rich?

“It takes hard work, a passion for what you do and luck.” And, indeed, it was an act of defiance and then luck that caused the Bronx-born Cooperman to discover his passion and skill as an investor. As a young man Cooperman’s parents pressured him into leaving New York’s Hunter College to enroll in dental school. After paying tuition and purchasing all of the necessary tools, he decided he hated it and quit after only eight days, returning to Hunter to finish his degree. “It was an embarrassing and very traumatic time in my life,” he recalls.

In order to fulfill graduation requirements, he took economics classes as electives. He got As, and this led to Columbia Business School, which led to Goldman Sachs in 1967. “I found what I was interested in and never looked back,” he says.

With a net worth of $2.5 billion, Cooperman recently joined Bill Gates and Warren Buffett in pledging to give more than half of his fortune to charity. “Money enables you to put bread on the table at first, but it also enables you to give back in a big way.”

Images From top: Michael Prince / Corbis Outline, John Abott / Corbis, Getty Images

Kelly Phillips Erb

TAX LAWYER AND BLOGGER

“The best money advice that I ever got was not to be afraid to spend it, which I know is weird, because most of the time people say you need to save,” says tax lawyer Kelly Phillips Erb. “But sometimes to make money you have to spend it, whether that’s paying for college, buying a house, buying a good stock or investing in a business.”

Erb knows whereof she speaks. At 40, with three kids, she still owes $140,000 on student loans for her two law degrees but doesn’t regret taking on the debt. She practises law with her husband in the Philadelphia suburbs and blogs as Taxgirl. In eight years of writing, she’s built a reputation as a voice of common sense and someone who can explain taxes in plain English.

“Don’t let the tax tail wag the dog.” In other words, you should think about taxes when you invest, but “don’t be so paralysed by the tax consequences that you miss out’’. That goes for selling, too—don’t keep holding an asset you should get rid of just because you hate paying capital gains tax.

Money is “necessary, but that doesn’t mean it should always be first”.

FOUNDER, THE VANGUARD GROUP

In 1949, Jack Bogle was a Princeton student working a summer job as a runner at a Philadelphia brokerage firm when an older runner took him aside and said, “Bogle, I want to give you the best stock market advice that you ever had in your life: Nobody knows nothing.” And it was the best advice, since it served as the “quasi-inspiration” for his creation of the first stock market index mutual fund in 1975. “If nobody knows nothing, you own everything,’’ he reasoned.

The index fund and the 84-year-old Bogle’s unwavering commitment to low-cost, long-term index investing helped Vanguard grow into the world’s largest mutual fund company. The twin ideas are also at the heart of his advice for young investors who want to get rich: Save early and regularly through a 401(k) or IRA, and put most of your money in a low-cost stock index fund. That way, he says, you benefit from “the magic of compounding returns” without having them “destroyed or severely eroded by the tyranny of compounding costs.”

Bogle, who grew up poor in the Depression, says he thinks about money as existing on three levels: Enough for a “decent living”, enough for “the pursuit of happiness” and a final level of even greater wealth “that should not be about flagrant and conspicuous consumption” but about helping those less fortunate. “Our Founding Fathers would have been appalled at the gross excesses of today’s society.”

FOUNDER, LEARNVEST

“The best piece of money advice I’ve ever been given is to look at every single one of my expenditures and to not think about it in today’s dollars but in future dollars. So, for example, if I’m buying something that costs $300, what’s the opportunity cost of not having that $300 in my retirement account? Maybe it’s $20,000,’’ says Alexa von Tobel, the 29-year-old founder of LearnVest, a personal finance advice site that recently became a registered investment advisor with the SEC.

“I want to live big when I’m older, and I’m willing to sacrifice a lot of these mundane things today that I would have spent it on otherwise,’’ adds von Tobel, who dropped out of Harvard Business School in 2009 to launch her company. She started by aiming at millennial women but found older folks and men (now 30 percent of users) were relating to LearnVest’s content, which is sprinkled with inspirational first-person accounts.

“The best thing you can do with your money in your 20s is to not make mistakes.” The big ones: Too much credit card debt and paying bills late. Screw those up and you might not be able to get a mortgage—or a job.

“Money is a tool that allows you to live your richest life. … If you want to be a painter. If you want to have lots of kids. … Whatever it may be. We only get to do this once, so you really want to focus on the things that you care about.”

BEHAVIOURAL ECONOMIST, DUKE UNIVERSITY

Ariely is probably the most important economist on the planet who has no formal training in economics. Rather, the 46-year-old American-born Israeli received his doctorate in psychology—and he concentrates on studying how people actually behave (irrationally) rather than how traditional economists would prefer them to behave (perfectly rationally).

That simple insight—and the complex, counter-intuitive implications—is the basis of both his academic research and his 2008 bestselling book, Predictably Irrational. “The key to being rich is saving and saving early,” Ariely says. The problem is that saving is a long-term behaviour and “in the whole repertoire of human behaviour, there are almost no behaviours in which we take the long-term future into account: Smoking, overeating, unprotected sex”.

Since saving is so hard, Ariely thinks we should rigorously audit our spending—and try to calculate how happy that spending really makes us. “We don’t always know … and because of this we need to experiment with more things. Imagine that one year you try an expensive vacation and one year you try the cheap vacation. Then you ask, ‘Does it matter which one? Does it change my happiness?’

“The other approach, of course, if you can’t save money, is to be really nice to your kids.”

CHAIRMAN, THIRD AVENUE MANAGEMENT

Contrarian value-investing legend Marty Whitman likes to compare equity investing to the study of abnormal psychology: “You’re trying to figure out what the masses think are going to happen to the securities’ prices. Stock markets can be capricious.” That’s why Whitman has always felt most comfortable investing in the most out-of-favour sectors of the stock market and has often gone after the bargain-priced debt of troubled companies going through bankruptcy restructuring. “You can buy things at 10 or 20 cents on the dollar.”

But Whitman’s affinity for debt securities doesn’t extend to leverage when it comes to the average investor. “If you are going to be a passive, minority investor, don’t do it with borrowed money,” he says. “Bubbles are bound to occur, and you can’t insulate yourself from those events if you have large amounts of borrowings.”

Given that 42 percent of his flagship $2.7 billion Third Avenue Value fund is devoted to foreign equities like South Korean steelmaker Posco, it’s not surprising that Whitman advises those looking to build wealth to first invest in a good, well-rounded education.

“The greatest courses that I ever took, and that had the most influence on my life and career success, were demography and Russian history,” says Whitman, 88, who served in the Pacific during World War II and graduated from Syracuse University in 1949. Population flows, politics and social interactions are often guiding lights for global investors. Whitman is currently worried about Europe but continues his bullish stance on Hong Kong. “Understanding global flows takes more than being an expert in financial accounting,” he says.

BARON CAPITAL

When it comes to the trappings of a successful Wall Street career, growth-stock mutual fund magnate Ron Baron of $18 billion Baron Funds doesn’t shy from flaunting it. Just before the financial crisis he famously spent $103 million for a 40-acre oceanfront estate in East Hampton, New York. He’s also booked celebrity acts like Celine Dion, Elton John and Jon Bon Jovi for company conferences and claims the best seats when he attends matches played by Manchester United, the soccer team in which his funds own a big chunk.

But Baron, 70, who hails from Bruce Springsteen’s stomping ground in New Jersey, insists that attaining the good life takes hard work. “I subscribe to [Malcolm Gladwell’s] theory that you need 10,000 hours practising to be good at anything,” he says. “There are no shortcuts.”

Early in his career Baron logged long hours at Wall Street brokerages like Herzfeld & Stern, but he admits at least one simple piece of advice gave him an edge.

Says Baron, “I had been involved in short sales for a couple years, and the managing partner, a senior trader, called me in. He said ‘Ron, you’re a very good analyst, but you’re wasting your time on short sales; show me the short sellers’ yachts.’ ”

Baron took the advice, went long, and the Dow has appreciated 19-fold since.

Images : David Yellen / Corbis

Larry Kotlikoff

ECONOMIST, BOSTON UNIVERSITY

Larry Kotlikoff learnt his most valuable financial lesson—to diversify—while a young associate professor at Yale from a cartoon taped to his colleague James Tobin’s office door. Tobin had just won the 1981 Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on the relationship of different financial markets and risk, which he summarised for reporters as: “Don’t put your eggs in one basket”—inspiring next-day headlines and the cartoon.

Kotlikoff thinks investors should learn from behavioural economics research that shows how psychologically painful people find it to reduce their standard of living. When it comes to risky investments, use only assets above what is needed to support your current lifestyle, he says. “It’s like gambling at the casino. Leave your wallet at home and don’t spend your winnings until you’ve left the casino.”

Kotlikoff, 62, has incorporated the same behavioural insight into his ESPlanner software, which helps users calculate the optimum amount to spend and save so they won’t feel deprived in retirement or unnecessarily strapped right now. He’s a fan of inflation-indexed annuities as a way to smooth consumption. The ultimate goal? Before you die, spend any money you’re not leaving to heirs or charity. The title of one of his 16 books says it all: Spend ’Til the End.

“Money to me is security and fun, but it’s not really happiness.”

FINANCE PROFESSOR, COLUMBIA BUSINESS SCHOOL

Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen pounds nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.

Renowned value investing professor Bruce Greenwald has committed those words—referring to David Copperfield’s feckless optimist Wilkins Micawber—to memory. Micawber lives beyond his means and ends up in debtors’ prison. For a college professor who consults regularly with the world’s top hedge fund managers and is often referred to as the “guru to Wall Street gurus”, remembering to keep one’s spending in check isn’t always so easy.

Greenwald, 67, has two constructive pieces of advice for those seeking to become truly wealthy. “First, you have to be very concentrated, develop an expertise like many entrepreneurs do.” For investors it means being willing to take concentrated positions. He notes that in Warren Buffett’s early years he developed an expertise analysing insurance companies.

“Secondly, you have to get your hands on somebody else’s money,” he says bluntly. “You need some kind of safe leverage, not borrowed money to be called.”

“To me money is absolutely irrelevant,” exclaims Greenwald loudly, with a chuckle. Living among academic colleagues, Greenwald says, he avoids ostentatious displays of wealth and heeds Micawber’s Principle. At his parents’ direction he carefully adjusted his standard of living when he first became a professor in 1973 and now earns so much from his various consulting gigs that he has no need for the money and gives most of it away.

CHIEF EXECUTIVE, STARWOOD CAPITAL GROUP

“Pay attention to the big themes, because that’s what will help you earn 10 times your money,” says real estate mogul Barry Sternlicht, who initially built his hotel empire by scooping up the commercial loans of distressed savings and loans at crisis-related government auctions in the early 1990s. But, warns Sternlicht, “if you focus too much on the micro, then you can be obliterated by the macro and vice versa”.

Recently Sternlicht, 52, has been taking advantage of another big fire sale and recovery theme, as his Starwood Property Trust REIT bought one of the largest managers of distressed commercial real estate, LNR Property LLC, for $1 billion in January.

Sternlicht, who earned a liberal arts degree from Brown University before getting his MBA from Harvard, claims that another key to success is to remember that “you don’t know anything ever” and that “you have to be willing to change your mind”. “As the facts change,” he says, “change your thesis. Don’t be a stubborn mule, or you’ll get killed.”

He mentions a Miami condo deal he recently passed on. “I wanted desperately to be in Miami, then my staffers told me that there are 130 projects under construction. So I changed my mind.”

Another important tactic has been to study outliers, rather than eliminate them, as the statistically minded might recommend. “You can learn everything that there is to know about the industry or the player from the company that is performing better or worse.”

Images From top: Michael Prince for Forbes, Mathew Furman for Forbes, Getty Images

Robert Shiller

ECONOMIST, YALE UNIVERSITY

Robert Shiller, perhaps best known for co-inventing the Case-Shiller Home Price Index, says the American dream of building wealth through homeownership is a fallacy. “I’ve documented that home prices in real terms didn’t increase from 1890 to 1990,” he says. “That was the bubble thinking, but it’s still fresh in our minds.”

How do you get rich, then?

“Go into finance or a related field. It’s a lifetime decision,” advises Shiller. “Finance is the technology for making things happen. Accountant, auditor, marketmaker … these are big occupations.” Shiller lectures his students that mathematics, astronomy, sociology are all very appealing, but there are no jobs in them.

Shiller says his thesis supervisor, MIT economist Franco Modigliani, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1985, taught him not to trust market efficiency because it was only a half-truth. He says Modigliani’s papers on how inflation distorts markets prompted him to invest all his money in the stock market in the early 1980s as Paul Volcker’s rate hikes kiboshed inflation and sent the stock market soaring.

Shiller tells his Yale students: “If you are wealthy that means you are powerful, and you have to care about others.” He then requires them to read Andrew Carnegie’s 1889 essay, ‘The Gospel of Wealth’, which instructs the rich to recirculate their wealth through philanthropy.

ECONOMIST, A GARY SHILLING & CO

“Play in your own sandbox,” says economist and longtime Forbes columnist Gary Shilling, known for his prescient predictions of the demise of the housing bubble and for riding long bonds for three decades of the most profitable bond bull market in history. “The biggest mistake people make is when they get stars in their eyes about the killing someone else has made. That’s what fuelled the dotcom bubble and prompted people to own a half-dozen houses.”

Shilling, 76, likes to tell younger people the tale of the 1911 race to the South Pole between Great Britain’s Robert Falcon Scott and Norway’s Roald Amundsen.

The Norwegian adapted many techniques already in use by Inuit Eskimos in the Arctic, including sealskin clothing worn inside out so the hairs wicked away moisture and kept his men warm and dry. He used sled dogs and fed on seals and penguins along the way. By contrast, Scott bet on the superiority of ‘modern’ science. After all, Great Britain’s technology had been instrumental to its world dominance.

Says Shilling, “Scott used crawler tractors, which either sunk in the ice or were abandoned. He took Siberian ponies, which breathe and sweat through their skin. They promptly got ice sheets on them and died.” Norway planted its flag first with no casualties. The entire British team perished.

“The point is, not everyone is Nobel Prize quality,” says Shilling. “Don’t try to reinvent the wheel. Most of us will be better off in terms of what we can do for the world by just intelligently and efficiently applying what is already well known.”

FOUNDER, TIGER MANAGEMENT

“Hedge funds are the antithesis of baseball,” says Julian Robertson, 80, billionaire founder of one of the most successful hedge funds ever, Tiger Management. “In baseball, you can hit 40 home runs on a single-A-league team and never get paid a thing. But in a hedge fund you get paid on your batting average. So you go to the worst league you can find, where there’s the least competition.”

This rule has guided Robertson’s investing strategy and is a big reason he has found some of his best ideas “buying into forgotten markets”, which he thinks are mostly in emerging countries today. Says Robertson, “I suppose if I were younger, I would be investing in Africa.”

One emerging economy Robertson has a big stake in is New Zealand, where he owns vineyards, farmland and three world-class golf resorts.

Ironically, it was a rash decision in 1978 to take a sabbatical from the brokerage business and move to New Zealand to pen an autobiographical novel, his wife and two young children in tow, that resulted in starting Tiger. Two years later, Robertson gave up writing to return to Wall Street.

The best money advice he ever got came from his father, a textile executive in North Carolina, who advised him to save to build up capital and to move to New York City to train on Wall Street. Robertson also stresses the importance of understanding numbers. “Accounting was the course that helped me more than anything.”

AUTHOR

When Dick Bolles first published What Color Is Your Parachute? in 1970, he had no idea the outsize impact his career guide would have. “I never dreamt the job hunting problem was so widely faced. … The book would have sold 10 copies if you got the help you needed at school.” Instead, the job-seekers’ bible has gone through 42 annual editions, sold 10 million copies in 20 different languages and, in 1994, was named one of the 25 books that “have shaped readers’ lives” by the Library of Congress.

Bolles himself remains firmly on the job at 86, spending roughly four hours a day doing research and answering each and every one of the 6,000 emails and letters he receives each year. He regularly dispenses four pieces of advice.

Foremost: “Don’t make money the most important thing about finding a job.” Instead, weigh salary against a position’s responsibilities, location, working conditions and growth opportunities. “You might be willing to take a pay cut to get one of those other factors.”

Second, Bolles advises delaying talk of salary, vacation time or health benefits until it’s clear they want you. “Once the potential employer gets to know you better, they might in fact decide that you’re worth more than the average person.”

Bolles also stresses the importance of keeping a diary. A weekly record of accomplishments at your current job will make it easier to discuss your role, in detail, when hunting for a new one. And as a finishing move, he advocates being bold. “Somebody told me the best way to end an interview is to ask: ‘With all we’ve discussed, can you offer me this job?’ When I first heard that, I thought that’s kind of cheeky, putting the person right on the spot. Turned out it was exactly true.”

Images from Top: Mirjam Donath / Reuters, Getty Images, David Yellen for Forbes, Michele Clement for Forbes

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)