The Truth about Bain Capital

The house that Romney built has much more than an election-driven image problem. Just ask its investors

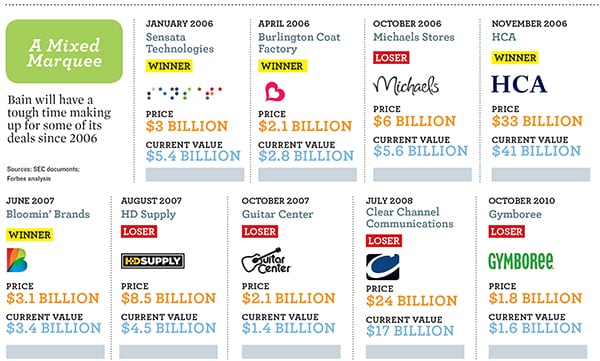

Among the private equity deals of this century, HCA stands among the very best. Bain Capital partnered with KKR and Merrill Lynch to buy the hospital chain for $33 billion in November 2006. Bain invested $1.2 billion for a 25 percent stake and recovered almost all its money with a trio of special dividends in 2010. The Boston firm pulled out another $457 million when HCA went public again in March 2011 and still owns shares worth almost $3 billion. Despite the financial crisis and periodic whiffs of scandal swirling around the for- profit hospital chain, HCA is worth 26 percent more today than it was seven years ago, and Bain investors have more than tripled their money.

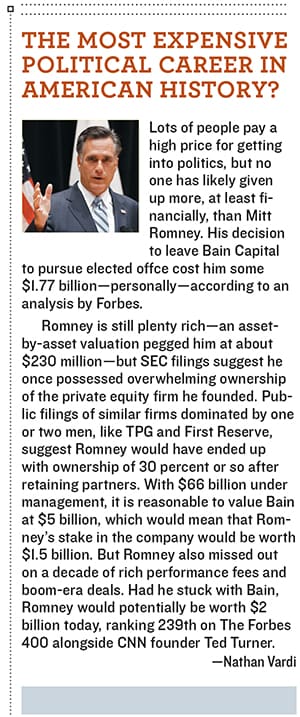

If only they could all turn out like HCA. But they haven’t. Not even close. Actually, few of Bain’s biggest deals since buying HCA have panned out so far, leaving it with a decidedly middling recent investment record far outstripped by its mythology. Bain Capital has endured more dissection, debate and criticism this year than any firm in the half-century-old history of private equity, owing to its founder, Grand Old Party (The Republican Party) presidential candidate Mitt Romney, who launched the firm in 1984. While the White House and Romney focus on Bain’s job-creation record, no one has gauged the firm using industry-standard metrics to see how well it has performed in its core mission: Making money for its partners and investors.

An exclusive analysis of the firm’s returns by Forbes reveals that despite the hype surrounding Bain, investors in the firm’s biggest funds, raised in 2006 and 2008, would have been better off in a simple stock index fund. While Bain churned out serious returns for partners and investors during Romney’s tenure, it’s that reputation, rather than results, that has carried Bain for the past decade. Stephen Pagliuca, managing director, Bain Capital, defends the firm’s record: “We are in the business of being long-term right.” Over the past three months, Forbes dug into the financial performance of every company Bain has invested in for the past decade, and the returns of its funds that raised some $42 billion in capital and commitments since Romney stopped working there in 1999. We also spoke to some of Bain’s competitors and analysts, to understand how the firm does business. What we found:

• • While funds raised through 2004 maintained the upper-quartile performance, returns for later funds—their biggest—have lagged as the company engineered multi-billion-dollar buyouts of fragile consumer-dependent companies like Toys “R” Us, Burlington Coat Factory and Guitar Center at the peak of the 2005-08 private bubble. Those investments may yet recover, but they speak to a culture where reverent faith in decades-old techniques, rooted in consulting, have not kept pace with a new age of dealmaking.

• • Bain exemplifies a worrisome trend for private equity as a whole. Megashops like Bain, with tens of billions to deploy and an insatiable need to buy, make profitable exits increasingly difficult. Mix in the meltdown and the tepid recovery, and you’ve got a toxic brew for investors, which include some of the nation’s largest pension funds.

Clear Channel Communications epitomises all three of these issues. Bain and buyout firm Thomas H Lee Partners bought the nation’s largest group of radio stations for $24 billion in July 2008, including $2.1 billion in equity, just in time to watch the advertising market collapse along with the US economy. Loaded with $21 billion in debt and a $1.5 billion annual interest tab, Clear Channel barely earns enough to cover its interest payments and capital expenditures. And even giving it an Ebitda multiple akin to the far more profitable Disney, for example, the company is worth perhaps 70 percent of what Bain paid for it. “It’s extremely, extremely levered—it was one of the last deals done during the bubble,” says Karen Klapper, a debt analyst with CreditSights. Her appraisal of Bain is the ultimate back- handed compliment: “They’re doing a good job managing their balance sheet and pushing out maturities so they don’t go into bankruptcy.”

Avoiding bankruptcy wasn’t the goal when 37-year-old Romney established Bain Capital in 1984. With the encouragement of Bill Bain, Romney and two other Bain & Co consultants set out to apply his mentor’s philosophy to private equity, making companies more valuable by increasing efficiency and finding new markets. Until his departure, Romney reportedly held all of Bain Capital’s stock and made a fortune by participating in the firm’s deals.

“It was eye-opening, the techniques they were using to grow businesses and make business get better,” says Pagliuca, whom Romney hired as a summer associate at Bain & Co in 1981. “The rationale was, this consulting work that worked so well with companies could be used for investments, too.” Romney built a team of dealmakers who mostly resembled him— young, many of them Harvard Business School graduates—who focussed on rigorous analysis instead of investment banking tricks like loading a target with debt so it could spit out a quick dividend.

For two decades it worked, spectacularly well. Bain Capital backed Staples, for example, after executives there determined that small businesses would patronise large stores carrying all their office supplies in one place. Staples returned 5.75 times Bain’s investment. Bain’s exits logged a staggering 173 percent annual internal rate of return through the end of 1999, when Romney stopped his day-to-day work to head the struggling Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City.

Romney sold his stake in the firm to his partners in 2002 during his successful run for governor of Massachusetts, though his presidential campaign has revealed Bain still provides a lucrative annual income stream from deals he invested in. The biggest asset he bequeathed, in retrospect: A track record that turned Bain Capital into a fund-raising machine, as pension funds, endowments and rich families sought to capture some of those dazzling returns. With management of the firm passed on to about a dozen long-serving MDs, Bain raised 10- and then 11-digit funds. In 2004, it launched the $3.5 billion Bain Capital Fund VIII; in 2006, the $8 billion Fund IX; in 2008, the $10.7 billion Fund X. On some of these funds Bain has reportedly had the moxie to demand—and get—a 30 percent slice of all profits, rather than the standard 20 percent.

Bain’s Fund VII, a quaint $2.5 billion, which started in 2001 just before Romney’s formal exit, was its only true success of the decade, returning $4.4 billion to investors for a solid 29 percent internal rate of return so far, according to PitchBook, a private equity monitoring service.

The three giant post-Romney funds, however, would be considered failures if liquidated right now, all succumbing to the traps too many other firms fell into: The huge sums raised made generating returns difficult and forced them to chase deals at nearly any cost, thus creating an asset bubble.

Fund VIII has generated an 11 percent IRR since 2004, placing it in the lower half of funds PitchBook tracks. Fund IX has returned 2.6 percent: In the upper half, says PitchBook, but badly trailing the S&P 500. And then there’s giant Fund X, which has invested $7 billion of the $10 billion-plus raised. It’s actually lost money, according to PitchBook: Specifically, –2 percent compared to a 14 percent return in the S&P over the same period. Even against private equity peers, Fund X ranks in the bottom quartile.

Bain’s model hasn’t changed. As in the Romney years, Bain assigns teams of analysts to study potential acquisitions, often for months, before mounting a takeover bid. If Bain wins, it has an internal group of 70 consultants who advise portfolio companies on everything from upgrading their computer systems to calculating the profitability of a two-for-one special on fast food. The problem is that the rest of the industry has caught up to Bain: Blackstone, Carlyle and nearly every other large firm now deploy internal consultants to effect change among their acquisitions.

“Bain Capital was very different 10 to 15 years ago, but other firms over time have copied that,” says Steven N Kaplan, a professor specialising in private equity at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. “The reason they were able to raise so much money in 2006, 2007, 2008 was because they performed so well in the past.”

“What they started to do was believe a bit too much in their ability to fix companies, and they started paying more,” adds a partner at a competing private equity firm who praises Bain’s management skills but says it couldn’t overcome high prices paid for companies like Clear Chan- nel, Guitar Center and Gymboree. “Those improvements don’t yield a lot of profit in a downturn.”

Bain Capital’s partners can obviously do the math. They’ve reportedly lowered their profit share back to 20 percent. And while they’ve been almost uniformly silent this year, mutely watching as their firm’s brand has been made synonymous with greed, Pagliuca and John Connaughton, another managing partner and a close pal of Romney’s, agreed to discuss their track record with Forbes, deal by deal. The two partners argue, their bubble-era purchases may have declined in value from the peak, but they will still generate solid returns for investors over time. Take Clear Channel: Bain’s financial moves have drawn a lawsuit from disgruntled investors who accuse Clear Channel of extracting a $650 million loan from its 89 percent-owned outdoor advertising business at a ‘sweetheart’ rate of 9.5 percent (Clear Channel bonds are currently trading with over a 20 percent yield, according to Bloomberg) and loading the unit with $2 billion in debt so it could upstream a dividend to its cash-strapped parent.

Bain executives declined to comment on pending litigation. But Connaughton says Clear Channel will pay off eventually because the company is gaining market share at the expense of its smaller competitors. Bain has guided it to add digital screens to its billboards and start an online broadcasting service, iHeartRadio, to expand the marketing reach of its 866 domestic radio stations. Revenue climbed to $6.2 billion in 2011 from $5.6 billion in 2009, and the company swung from a $3.7 billion loss to a $1.1 billion operating profit.

“We’ve been growing the profit line for the last three to four years quite successfully” despite a flat ad market, says Connaughton, who joined the firm in 1989 and is a former Bain & Co consultant and Harvard Business School grad. “Like any cyclical asset that goes through a down cycle, you have to ask yourself, ‘Is it a better asset than when you bought it?’ Clear Channel is.”

Bain and two other private equity firms bought Home Depot’s wholesale supply business for $8.5 billion in 2007, just as the housing market imploded. Sales fell 22 percent from 2009 to 2011, and the company expects to burn through $200 million in cash this year. At eight times cash flow it’s worth $4.5 billion.

Bain plunged into retail because the firm’s executives think they understand it better than most, thanks to their early success with Staples. The firm also likes restaurants, having quadrupled its money on the $1.5 billion buyout of Burger King in 2002. Now Bain owns Bloomin’ Brands, operator of Outback Steakhouse, Carrabba’s Italian Grill and other chains. It’s worth more than the $3.1 billion it paid in 2007, and Bain holds $1 billion in stock, a paper profit on its $874 million investment.

Connaughton said a team of Bain executives spent more than a year studying their latest restaurant acquisition, the Skylark chain in Japan, which they bought for $2.1 billion last year. Bain figured it could use strategies it honed at Domino’s Pizza, Burger King and Dunkin’ Donuts to upgrade Skylark’s marketing as well as an electronic tracking system that helps improve the quality of the food and service. Its executives will push Skylark to adopt some of the aggressive discounts and advertising campaigns Bain used to increase sales at its Domino’s Pizza operation in Japan.

“One of the best things we’ve done with a lot of the restaurant companies is drive differential growth through promotion,” Connaughton says. For every billion-dollar dud like Gymboree and Guitar Center you bring up to Pagliuca and Connaughton, they counter with something like Sensata Technologies, a maker of electronic sensors and controls Bain bought from Texas Instruments for $3 billion in 2006. The timing couldn’t have been worse: Three years later two of its biggest customers, GM and Chrysler, were in bankruptcy, and auto sales plunged. But Connaughton says Bain’s consulting model of private equity worked: They thought it could invest in new technology that increased the share of the electronics it put in each car. “We could put more controls and sensors in the cars,” he says, even if the overall market was flat.

Bain took Sensata public in March 2010 and since then has sold stock for $1.4 billion, more than returning the $985 million in equity it put in. It still holds shares worth $2.8 billion, and the company is worth $5.4 billion.

Bain loyalists also reject the charge that the firm has made money by slashing employment and paying itself debt-fuelled dividends. A close examination of the 40-odd companies it still holds a stake in, reveals that most have maintained or increased capital expenditures—even as they took on much higher levels of debt.

Pagliuca says he’s used to the intense scrutiny his firm is getting because of its famous founder: “The good news is this isn’t the first time one of our people has gone into public service,” says Pagliuca, who ran for US Senate in Massachusetts as a Democrat in 2009.

“You would have thought that if we had something like 1929, PE portfolios would have been wiped out,” he says. “But we expect our companies will de- liver strong returns to our investors.”

Bain Capital remains very much in the game. The talent is not fleeing for the exits, even after the election scrutiny. And they can still raise money, as evidenced by this year’s $2.3 billion Asian fund. But will Bain’s recent investors, who bought into the Romney-era track record and hype, earn more by owning companies like Clear Channel, Burlington Coat Factory and Toys “R” Us over the next five years rather than just riding the S&P? Especially once Bain’s fees are accounted for? Probably not.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)