The Secret Sauce in 5-Hour Energy

Manoj Bhargava, the mystery man behind 5-Hour Energy, has taken one of the stranger paths to billions in the annals of the American Dream

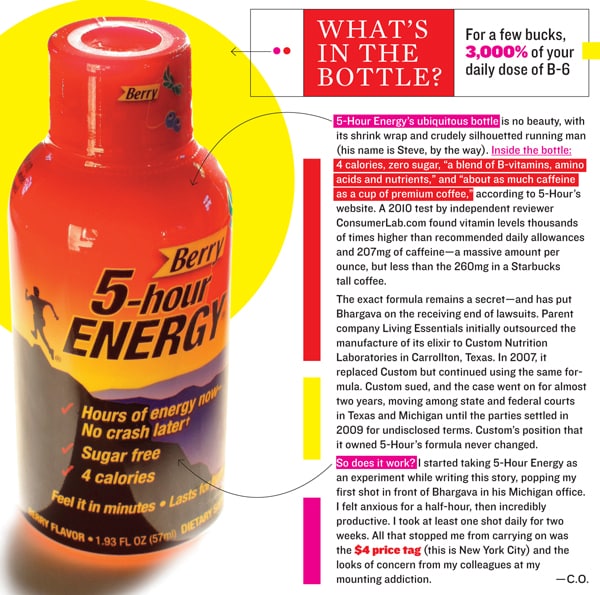

In one corner of Manoj Bhargava’s office is a cemetery of sorts. It’s a Formica bookcase, its shelves lined with hundreds of garishly coloured screw-top plastic bottles not much taller than shot glasses. Front and centre is a Cadillac-red bottle of 5-Hour Energy, the two-ounce caffeine and vitamin elixir that purports to keep you alert without crashing. In eight years 5-Hour has gone from nowhere to $1 billion in retail sales. Truckers swear by it. So do the traders in Oliver Stone’s 2010 sequel to Wall Street. So do hungover students. It’s $3 a bottle, and it has made Bhargava a fortune.

His company, Living Essentials, is the biggest player by far in the energy-shot market, and not because 5-Hour is so delicious. Chalky cough syrup is more like it. The reason Bhargava has won is that he plays tough. Sitting in that cemetery are a dozen or so neon copycats with names like 6-Hour Power and 8-Hour Energy. Each has been sued, bullied or kicked off the market by Living Essentials’ lawyers. In front of each are little placards with a skull and crossbones drawn in felt-tip pen. Bhargava points at the gravestone of one of his late competitors and says with a chuckle, “Rest in peace.”

The privately held Living Essentials doesn’t report revenue or profits, but a source with knowledge of its financials says the company grossed north of $600 million last year on that $1 billion at retail. The source says the company netted about $300 million. Checkout scan data from research firm SymphonyIRI say that 5-Hour has 90 percent of the energy-shot market. Its closest competitor, NVE Pharmaceuticals’ Stacker brand, has just over 3 percent.

Yet Bhargava, 58, is so under the radar that he barely registers on Web searches. His paper trail is thin, consisting primarily of more than 90 lawsuits. This is his first press interview. “I’m killing it right now,” he says, adjusting a black zip-up cardigan from behind the table of a soulless conference room in a beige low-rise building in a suburban business park in Farmington Hills, Michigan. “But you’ll Google me and find, like, some lawyer in Singapore.”

Vague and inscrutable is how Bhargava likes things. The names of 5-Hour’s parent company, Living Essentials LLC, and that company’s parent firm, Innovation Ventures, are purposely bland. “They were intended as placeholders, and they stuck,” he says, smiling.

Colleagues and acquaintances uniformly describe Bhargava as “humble,” and he seems proud of his frugal lifestyle: His ancient flip phone, his cheap office furniture, the modest two-storey home he shares with his wife and 20-year-old son. Yet, over vegetarian lasagna at Antonio’s, his favourite strip-mall Italian joint off Detroit’s Twelve-Mile Road, Bhargava says, apropos of nothing: “I’m probably the wealthiest Indian in America.”

The rise of 5-Hour began in the spring of 2003, when Bhargava found himself at a natural products trade show in Anaheim, California. At one booth the sales reps peddled a 16-ounce concoction claiming to boost productivity for hours. Bhargava took a swig. “For the next six or seven hours I was in great shape,” he says. “I thought, Wow, this is amazing. I can sell this.” Right away, though, he knew 16 ounces wouldn’t sell. He didn’t want to compete with Red Bull, at the time new to the market. Nor did he want to share fridge space with Coke or Pepsi. “I thought, If I’m tired, am I also thirsty? Is that like having a headache and a stomachache? It didn’t make any sense.” He glanced at the ingredients label and made a mental note.

Six months later his version was on the shelves, two ounces of caffeine-infused B vitamins such as niacin mixed with acids like taurine.

Bhargava’s team still had to convince stores and buyers alike that their product was safe. The initial job of getting 5-Hour Energy on the shelves went to Rise Meguiar, Living Essentials’ vice president of sales and the only woman on a team of 17. Health chain GNC was the first to bite, agreeing to stock 5-Hour in 1,200 of its stores in 2004. Slowly but surely, Walgreens, Rite Aid and regional chains like Sheetz followed.

“It was never an easy sell,” says Meguiar, who aimed from the start to get those little red bottles up at the cash register next to the gum and lighters. “Getting it next to the register isn’t hard. Keeping it there? Very hard. Anything that sells, the stores will try. To own that space is really hard.”

Meguiar’s greatest coup, one that now accounts for an estimated 15 percent of 5-Hour’s overall sales: The Walmart checkout aisle. The superstore sells all four 5-Hour flavours in every US store, plus 24-packs at Sam’s Club.

“What we did wasn’t rocket science,” says Bhargava. “It’s not the little bottle. It’s not the placement. It’s the product. You can con people one time, but nobody pays $3 twice.”

Bhargava was born in the prosperous city of Lucknow. His parents were well-off, with a villa surrounded by lush, award-winning gardens. They left for America in 1967, so his academic publisher father could get a PhD at Wharton. The family landed hard in West Philadelphia in a third-floor, $80-a-month walk-up with threadbare carpets on seedy 47th Street. They went from having servants in India to splitting one Coca-Cola four ways as a treat.

Teenaged Bhargava excelled at math. “It’s like in Good Will Hunting,” he says, raising a hand to mime Matt Damon’s chalkboard scrawl of algebraic equations in the film. “You see stuff or you don’t. I just see it.” He had no tuition money, but connived his way into interviews at competitive Philadelphia schools, offering to take math tests to prove himself.

Early on, he realised he didn’t much care what sort of business he was in as long as he was winning at it. At 17 Bhargava noticed that blocks of low-income homes in the roughest North Philly neighbourhoods were being razed and cleared. Bhargava bought a 1.5-tonne 1953 Chevy dump truck for $400 and started clearing out debris from the demolition. He’d find rats bigger than cats among the garbage and rubble. “The stench was mind-bending,” he says. He remembers hearing gunshots outside a crumbling house on crime-ridden Girard Avenue and learning an old man had been killed for $5. Still, Bhargava made $600 that summer—and resold the Chevy for $400. He didn’t care if the work was unglamorous. It was profitable.

He won a full scholarship to the Ivy League feeder Hill School before heading to college at Princeton in 1972. Bhargava lasted a year. The pretentious eating-club culture wasn’t really for him, and he didn’t find his math classes particularly challenging. “ ‘Annoyed’ would be a mild word for my parents’ reaction,” he says. He returned to Fort Wayne, Indiana, where his parents had settled and his father owned a plastics company. “There were no jobs; it was a disaster,” he says. “It was right before the oil embargo, the stagflation era.” He started reading books about a Hindu saint who’d spent his life on a spiritual quest. That, he thought, was something worthwhile. In 1974 he moved to India.

Bhargava says he spent his 20s travelling between monasteries owned and tended by an ashram called Hanslok. He and his fellow disciples weren’t monks, exactly. “It’s the closest Western word,” he says. “We didn’t have bowler haircuts or robes or bells.” It was more like a commune, he says, but without the drugs. He did his share of chores, helped run a printing press and worked construction for the ashram. Bhargava claims he spent those 12 years trying to master one technique: The stilling of the mind, often through meditation. He still considers himself a member of the Hanslok order and spends an hour a day in his Farmington Hills basement in contemplative silence.

Bhargava would return to the US periodically during his ashram years, working odd jobs before returning to India. For a few months, he drove a yellow cab in New York. When he moved back from India for good, it was to help with the family plastics business at his parents’ urging. He spent the next decade dabbling in RV armrests and beach-chair parts. He had no interest in plastics whatsoever but devoted himself to buying small, struggling regional outfits and turning them around. By 2001, Bhargava had expanded his Indiana PVC manufacturer from zero sales to $25 million (he eventually sold it to a private equity firm for $20 million in 2006). He decided to retire and moved to Michigan to be near his wife’s family. “Nobody moves on purpose to Detroit,” he says. His retirement lasted two months. He knew from his plastics success that the chemicals industry was ripe for exploiting. “Chemicals are really simple,” he says. “You mix a couple things together and sell it for more than the materials cost.”

Bhargava takes a shot of his creation every morning and another before his thrice-weekly tennis game. He shakes his head at the suggestion that taking shots infused with caffeine is at odds with his quest for inner stillness. “5-Hour Energy is not an energy drink, it’s a focus drink,” he says, turning one of the pomegranate-flavour bottles around in his hands. “But we can’t say that. The FDA doesn’t like the word ‘focus.’ I have no idea why.”

Bhargava claims to be the richest Indian in America—a title that officially belongs to Silicon Valley venture capitalist Vinod Khosla—but trying to untangle Bhargava’s business structure requires a 24-pack of 5-Hour Extra Strength. He could well be worth much more than Khosla’s $1.3 billion. Living Essentials’ closest comparable public company, energy drink giant Monster, trades at over 30 times earnings, making Bhargava easily a multi-billionaire on paper.

But Bhargava claims to have given away $1 billion in 2009, with a letter to Forbes from his attorney, David Lieberman of the Michigan firm Seyburn Kahn, to back him up. Tax returns of Bhargava’s US charity, the Rural India Supporting Trust, suggest a different narrative. Virtually the entire donation was in the form of a 45 percent stake in the privately held Living Essentials. Only a few million dollars was in cash.

Rural India then sold that 45 percent stake to Nevada 5, a private forprofit company. In exchange, Rural India got a note worth $623.6 million.

Bhargava’s accountant Paul Edwards of Plante Moran says his client is not a beneficial owner in Nevada 5—but another one of his associates says it is a vehicle for Bhargava’s philanthropy and affiliated with Innovation Ventures, the parent company of Living Essentials.

This kind of deal raises questions, says Roger Colinvaux, professor at Catholic University’s Columbus School of Law and an expert on tax and philanthropy. “If it were a private foundation, it would be prohibited from selling to a company related to a major donor.”

Rural India itself appears not to be giving much away. It lists total grants paid out in 2010 of just $4 million off a total asset base that by the end of that year had been stepped up to just over $1 billion. Bhargava can get away with this because he set up Rural India as something called a supporting organisation, or a group that financially supports other charities. Unlike a traditional private foundation, a supporting organisation has no mandated 5 percent minimum outlay, pays no excise taxes on investment income and has fewer self-dealing restrictions. Bhargava is not doing anything illegal here, just exploiting a loophole in the tax code many other big philanthropists have used as well.

Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley has been going after supporting organisations since 2002. “This structure permits a donor to donate assets to a charity, which then lends them back to the donor,” Grassley says. “This results in huge tax breaks for the donor with very little money actually going to those in need.”

The primary recipient of grants from the Rural India Supporting Trust is an organisation called the Hans Foundation, which works to improve the lives of India’s most needy.

Hans sends surgeons to combat epidemic levels of cataracts among the rural poor and devotes much-needed funds to women’s healthcare. A staff of 12 travels India looking for schools and hospitals to adopt rather than build from scratch. “We don’t do the work, but we have money,” Bhargava says.

Bhargava was originally vague and slightly taciturn when asked about the name of the foundation, describing Hans only as a former teacher, now dead. Only later, after much questioning, did he identify Hans as a guru called Shri Hans Ji Maharaj, spiritual leader of the Hanslok ashram where Bhargava spent those years pursuing a life of discipline as a monk. Bhargava talks of his monk days nonchalantly, accompanied by a characteristic dismissive shrug. “It’s a personal thing,” he says. “I don’t want to be a Jehovah’s Witness here proselytising.”

With 5-Hour now growing smoothly, Bhargava is on to the next thing—or three. He’s put most of the $100 million behind Stage 2 Innovations, a Detroit tech venture fund that’s already invested in clean engines, hydroponic farming and water desalination. To run Stage 2 Bhargava hired former Chrysler Group CEO Tom LaSorda, a barrel-chested auto industry veteran as gregarious as the slight, bespectacled Bhargava is reticent. Bhargava wooed LaSorda over a $12 plate of pasta under the dusty grapes hanging from the ceiling at Antonio’s.

“I said, ‘Hey, if you find any technology, bring it to me,’” says Bhargava. The fund’s first investment is in Hybrid60, a hydraulic engine technology that aims to increase fuel efficiency by 60 percent. LaSorda is testing it on trucks right now and eventually hopes to sell the technology to customers such as his billionaire buddy Roger Penske, who could retrofit his 225,000 rental trucks, the largest fleet in the US.

Across the room from their tester Penske truck LaSorda and Bhargava look approvingly at their other project: An indoor, software-controlled farm. Tiny basil plants are growing inside 12-foot-by-12-foot containers that look like giant tanning beds covered in tinfoil. Rows of lilac lights bathe the trays of basil, each pot fed the perfect amount of nutrients at the right pH level. It hums like an air-conditioning unit, a trickle of water barely audible. In two weeks each sapling will be exactly 8 inches tall. The hydroponic startup has set up 500 more of these farm fridges, which do the work of 500 acres of land, in another unused building Bhargava bought on Detroit’s outskirts. He thinks this invention could change agriculture in droughtprone Middle Eastern and African countries.

LaSorda says he has found himself having to explain who his mysterious partner is on more than one occasion. “The reaction I get is ‘Who’s this guy?’” LaSorda says. “Then I say, ‘The 5-Hour Energy guy,’ and they say, ‘Oh, sh**, he must be killing it.’ I say, ‘Yeah, he is.’”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)