The American dream is alive and well...

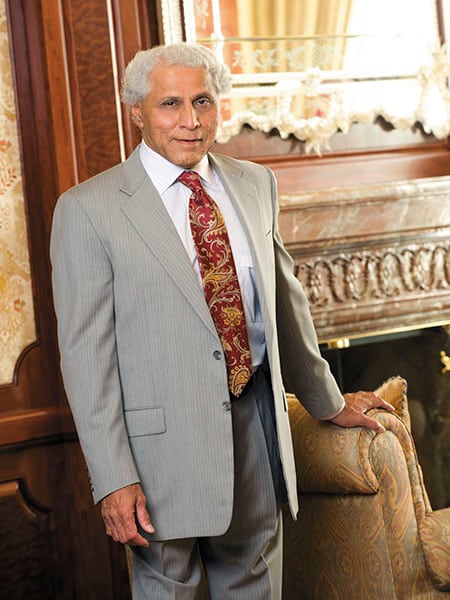

Thomas Peterffy was born in the basement of a Budapest hospital on September 30, 1944. His mother had been moved there because of a Soviet air raid. After the Soviets liberated Hungary from Nazi occupation, Hungary became a satellite state, labouring under a different kind of oppression: Communism. Peterffy and his family, descended from nobles, lost everything. “We were basically prisoners there,” he says. As a young man Peterffy dreamed about being free from that prison—in America.

At the age of 20 he hatched an escape plan. At the time Hungarians were allowed short-term visas to visit family in West Germany, and he took advantage of this. When his visa expired, like millions who have immigrated to the US illegally in recent years, he didn’t go back home. Instead he left for the US. Peterffy landed at John F Kennedy (JFK) International Airport in New York City in December 1965. He had no money and spoke no English. He had a single suitcase, which contained a change of clothes, a surveying handbook, a slide rule and a painting of an ancestor.

Peterffy went to Spanish Harlem, where other Hungarian immigrants had formed a small community, moving from one dingy apartment to another. He was happy, if not a bit afraid. “It was a big deal to leave home and my culture and my language,” he says. “But I believed that in America, I could truly reap what I sowed and that the measure of a man was his ability and determination to succeed. This was the land of boundless opportunity.”

Indeed it was. He got a job as a draftsman in a surveying firm. When his firm bought a computer, “nobody knew how to program it, so I volunteered to try,” he says. He caught on quickly and soon had a job as a programmer for a small Wall Street consulting firm, where he built trading models.

By the late 1970s Peterffy had saved $200,000 and founded a company that pioneered electronic stock trades, executing them before the exchanges were even digitised. In the 1990s he began to concentrate on the sell side of the business, founding Interactive Brokers Group, which has a market cap of $14 billion. Peterffy, 72, is now worth an estimated $12.6 billion.

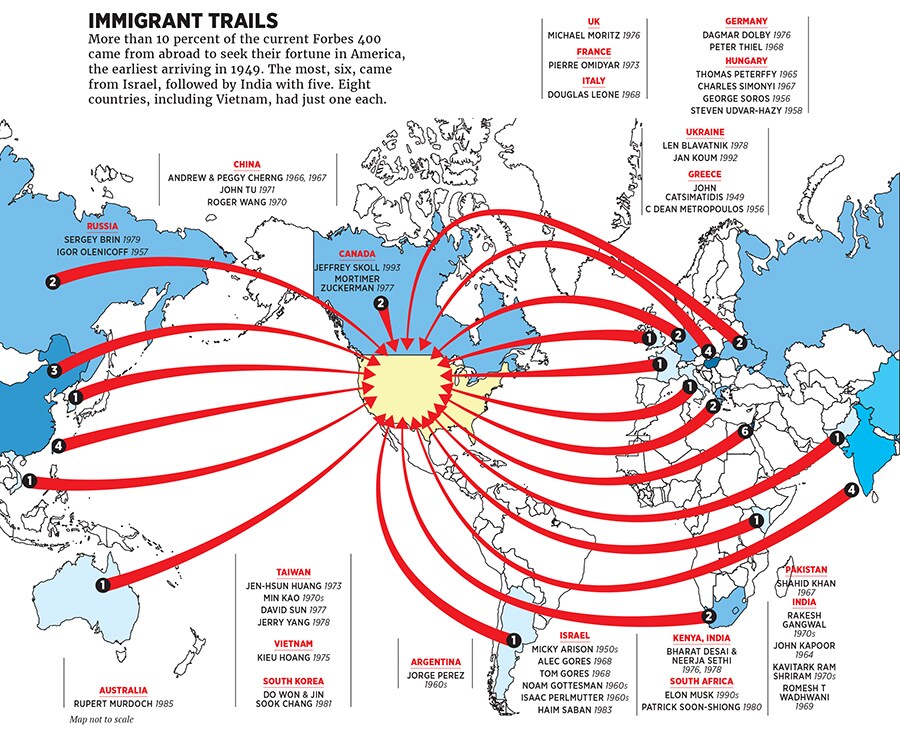

Thomas Peterffy embodies the American Dream. So does Google founder Sergey Brin ($37.5 billion). And eBay founder Pierre Omidyar ($8.1 billion). And Tesla and SpaceX founder Elon Musk ($11.6 billion). And Rupert Murdoch, George Soros, Jerry Yang, Micky Arison, Patrick Soon-Shiong, Jan Koum, Jeff Skoll, Jorge Perez, Peter Thiel. As well as a couple dozen others who also immigrated to the US, earned US citizenship—and then a spot on The Forbes 400.

Precisely 42 slots on The Forbes 400 belong to naturalised citizens who immigrated to America. That’s 10.5 percent of the list, a huge overperformance considering that naturalised citizens make up only 6 percent of the US population. (If you add noncitizens, about 13 percent of American residents are foreign born, but there is also a slew of noncitizen billionaires, such as Chobani Yogurt king Hamdi Ulukaya and WeWork founder Adam Neumann, who by dint of their passports don’t qualify for the 400 but still live, and create jobs, in the US.)

For all the political bombast about immigrants being an economic drain or a security threat, the pace of economic hypersuccess among immigrants is increasing. Go back 10 years and the number of immigrants on The Forbes 400 was 35. Twenty years ago it was 26 and 30 years ago 20. Not only is the American Dream thriving, as measured by the yardstick of entrepreneurial success, The Forbes 400, but it’s also never been stronger. The combined net worth of those 42 immigrant fortunes is $248 billion.

According to the Kauffman Foundation, immigrants are nearly twice as likely to start a new business than native-born Americans. The Partnership for a New American Economy, a nonpartisan group formed by Forbes 400 members Murdoch and Michael Bloomberg, reports that immigrants started 28 percent of all new businesses in the US in 2011, employ one out of every 10 American workers at privately owned businesses and generate $775 billion in revenue. Some of these businesses are small, of course, like restaurants and auto repair shops. But others aren’t: The National Foundation for American Policy, a nonpartisan research group, says that 44 of the 87 American tech companies valued at $1 billion or more were founded by immigrants, many of whom now rank among the richest people in America.

None of this should be a surprise. Thanks to technology, it’s never been easier to start a business of significance. And America’s perpetual entrepreneur class, for nearly a quarter-millennium, has been made up of immigrants.

Robert Morris left Liverpool at the age of 13, helped finance the American Revolution and signed the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Stephen Girard emigrated from France and started an American bank that underwrote most of the US government’s war loan during the War of 1812, saving the country from financial disaster. John Jacob Astor, a young musical-instrument maker from Germany, built a fortune in fur trading and real estate in the US, and became one of the country’s first great philanthropists. Fellow German Friederich Weyerhaeuser became an American timber mogul. Scotland-born Andrew Carnegie built one of the great fortunes in the US in the steel business and, like Astor, devoted his later life to giving it away. The founders of Procter & Gamble, Kraft and DuPont were all immigrants.

The very act of immigrating, exemplified by Peterffy, is entrepreneurial, a self-selected risk taken in an effort to better one’s circumstances. It’s a mind-set. “You leave everything you have and get on a plane,” says Forbes 400 member Shahid Khan. “You can handle change. You can handle risk. And you want to prove yourself.”

By and large the immigrants of The Forbes 400 fall into two baskets. Many, like Peterffy, came here to escape something. Sergey Brin’s family left Russia when he was six years old because of discrimination against his Jewish family. George Soros survived Nazi-occupied Hungary. Igor Olenicoff’s family was forced to leave the USSR after World War II because of their tsarist connections.

Others had enough privilege to live anywhere but saw America as the place of greater opportunity. Musk attended private schools in South Africa. Murdoch’s father was a knighted Australian newspaper publisher. Omidyar’s father was a surgeon.

Rich or poor, America’s entrepreneurial mind-set links them all. Americans-by-choice appreciate the opportunity and understand the corollary: That you can’t count on anyone giving you a break but instead need to make it yourself.

Do Won Chang and his wife, Jin Sook, arrived at Los Angeles International Airport on a Saturday in 1981 with not much more than a high school education the same year martial law was lifted in South Korea. He immediately scoured newspaper job listings, interviewed with a local coffee shop and by Monday was washing dishes and prepping meals on the morning shift. “I was making minimum wage. … It wasn’t enough to get by.” So he tacked on eight hours a day at a gas station and on top of that started a small office-cleaning business that kept him busy until midnight. Jin Sook worked as a hairdresser.

While pumping gas, Chang noticed that men in the garment business drove nice cars, inspiring him to take a job in a clothing store. Three years later, after he and Jin Sook saved $11,000, they opened a 900-square-foot apparel store called Fashion 21. First-year sales reached $700,000, and the couple began opening a new store every six months, eventually changing the chain’s name to Forever 21. They’re now worth $3 billion.

“I came here with almost nothing,” says Chang. “I’ll always have a grateful heart toward America for the opportunities that it’s provided me.”

For Shahid Khan, a Pakistani, the logical place to immigrate was the United Kingdom, “but the US was always the promised land for me.” In January 1967 Khan landed at JFK, his generation’s Ellis Island. His connecting flight to Chicago was diverted by a snowstorm, so the 16-year-old flew to St Louis instead and took a bus to Champaign, to the University of Illinois, where he was enrolled as an undergraduate. He had $500 in his pocket. Khan got a job working as a dishwasher at night after school for $1.20 an hour. “I was overjoyed. You just couldn’t get a job like that where I came from,” he says. “My immediate thought was, Wow, I can work. I can be my own man. I control my destiny.”

Khan eventually got a job as an engineering manager at Flex-N-Gate, an automotive manufacturer. A few years later, with $16,000 in savings and a Small Business Administration loan, he started his own company, which made bumpers for car manufacturers. He eventually bought out his old boss at Flex-N-Gate. His company now has $6.1 billion in revenues and employs around 12,000 people in the US. A plant he’s building in Detroit will employ up to 1,000 workers who will be paid $25 an hour. Khan is worth an estimated $6.9 billion.

He still immigrated to the UK in a small way: He bought the English Fulham soccer team. But lest anyone challenge his preference, he also owns that most American of billionaire assets: A National Football League franchise—the Jacksonville Jaguars.

America has another natural advantage that helps explain why so many immigrants are able to turn themselves into billionaires. The US educational system has traditionally been a beacon, drawing the smartest and most ambitious young self-starters from across the world. Over the past few decades the billionaire formula has been increasingly simple: Come to America for college, fall in love with the country and the opportunities (and perhaps a future spouse), and stay here after graduation, putting that education to use creating the innovations (and jobs) that yield Forbes 400 fortunes.

The number of college-educated immigrants in the US grew 78 percent from 2000 to 2014. Almost 30 percent of immigrants 25 or older now possess a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to the Migrant Policy Institute—a figure that almost exactly mirrors the percentage for native-born adults. And a disproportionate number of these immigrants study math, science and other STEM disciplines that fuel most modern fortunes. In 2011 three-quarters of the patents from the top 10 patent-producing universities in the nation had an immigrant inventor.

Romesh Wadhwani falls into that tradition. He attended India’s legendary IIT Bombay technical college but in 1969 came to America to pursue a PhD at Carnegie Mellon. He never left, founding Aspect Development, a software company, and Symphony Technology Group, a tech-focussed private equity firm, on his way to a $3 billion fortune.

“It would have been virtually impossible for me to have started my own company in India in those days. There was no support for entrepreneurs,” says Wadhwani. “There is a freedom in the US to dream big dreams, the freedom to achieve based purely on merit rather than family background or previous wealth or social status.”

Chinese-born Andrew Cherng observed a similar meritocracy when he arrived in Baldwin, Kansas in 1966 to attend Baker University on a math scholarship. He’d gone to high school in Japan and found “it was hard for Chinese to blend in with the Japanese.” A year later he met an incoming freshman from Burma named Peggy, whom he would later marry. “I didn’t have any personal possessions when I came,” says Cherng. “My drive came from being poor.”

In 1973 Cherng opened a restaurant, the Panda Inn, in California with his father, a master chef who had emigrated to join him. Ten years later he and his wife, Peggy, opened the first Panda Express in a mall in Glendale, California. Having earned a doctorate in electrical engineering and worked as an aerospace-software-development engineer, she incorporated systems that have turned it into a 1,900-store, quick-serve food chain, one of the largest in the US, with $2.4 billion in revenues. The Cherngs employ 30,000 people and have raised more than $100 million for charity. “In America nothing will stop you but yourself,” says Cherng.

Douglas Leone is another Forbes 400 member for whom an American education was a turning point. He was in middle school when he left Italy in 1968. His parents envisioned a life for him that included “upward mobility, something that wasn’t possible in Europe.” He wound up at Cornell and then earned postgraduate degrees from Columbia and MIT. “The American Dream is realised if you take advantage of the opportunity,” he says. “I used my education as a vehicle to put me in a position to do something.”

Leone worked sales jobs for the likes of Sun Microsystems and Hewlett-Packard before joining venture capital firm Sequoia Capital in 1988. He became managing partner in 1996. During his tenure Sequoia has invested in Google, YouTube, Zappos, LinkedIn and WhatsApp, and has played a role in the creation of countless jobs. “If I had to bet the over/under on one million jobs created by the companies we’ve been involved in, I’d bet the over,” he says.

Leone is now worth an estimated $2.7 billion. His immigrant experience, he says, has been invaluable. “Being an immigrant provides you with a drive, one that never goes away. I still feel it today,” he says. “Failure is not an option. I tell my kids that the only thing I can’t give them is desperation. And I apologise to them for that.” Spoken like someone who found quick success.

It should be noted, though, that in addition to the 42 immigrants, The Forbes 400 includes 57 people who are the children of immigrants, or 14 percent of the list (compared with 6 percent of US citizens over 18), pretty much shattering the image of America’s billionaire class as a bunch of blue bloods. That entrepreneurial hunger seems to continue for at least one generation. Sam Zell’s Jewish parents escaped Poland before the German invasion in World War II and came to the US. “My father used to say that in the United States the streets were paved with gold, and he never lost his appreciation for how lucky he was that he and his family were allowed to come here and prosper,” says Zell, who’s made $4.7 billion in private equity and real estate investing. “They worked very hard and were very patriotic and certainly instilled that in us.”

This election cycle’s immigrant- and refugee-bashing is a time-honoured tradition here, with each wave of newcomers taking its turn in the crosshairs of those who see them as job-stealing criminals. The Germans gave way to the Irish, the Asians to the Arabs, the Catholics to the Jews. These days the targets are Hispanics and Muslims. “We’ve gone through these various cycles over the years,” says Peter Spiro, a professor at Temple University who specialises in immigration law. “What’s meaningful is that we’ve always come out of them.”

What’s also meaningful is that despite all the hot air America, a land of immigrants, remains decidedly pro-immigrant. A 2016 Pew Research poll indicated 59 percent of Americans believe that immigrants “strengthen our country because of their hard work and talents” (33 percent believe immigrants “are a burden on our country”). Our citizens naturally intuit that any slight downward wage pressure for unskilled workers is more than overcome by all the growth and job creation that immigrants excel in.

But that dynamic could be challenged. The US has been toughening its visa requirements for skilled workers (the famous H-1B). The US has had the same visa and quota cap for skilled immigrant workers since 2004, even though demand for the visas has exceeded the mandated allotment.

In fact, the government has filled its quota within five days of opening it each year since 2014—at a time when a global economy means that many newly minted college graduates see more opportunity (or at least a fighting chance) in returning home.

As a result we’re increasingly drawing the world’s best and brightest, giving them access to our best knowledge—and then kicking them out, to compete with us from their original homeland.

So, what to do? Ask The Forbes 400 immigrants, including Peterffy, Khan, Wadhwani and Cherng. Even with their varied backgrounds, they agree on three broad principles.

First, educated and highly motivated immigrants should be encouraged, not discouraged, to come to the US (President Obama has championed a proposal to admit immigrant entrepreneurs more easily—raise $100,000 from qualified investors and get a “startup” visa—but it’s been bottled up in congressional partisan gridlock. A workaround proposal, not subject to congressional approval, was recently announced by the Department of Homeland Security and would grant temporary status to immigrants with an ownership stake and an “active and central role” in an American startup.)

Second, American borders should be more secure when it comes to illegal immigrants. And third, there should be a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants already in the US, which includes registering, paying taxes and following the law.

Perhaps this can help create some consensus, one that ensures that the American Dream stays exactly that. How fitting if it proved to be another billion-dollar innovation dreamed up by immigrants.

With reporting by Samantha Sharf, Grace Chung and Mrinalini Krishna.

Hacking the Visa Racket

America’s immigration system almost killed Instagram.

Back in 2009, frustrated with his inability to get a work visa, co-founder Mike Krieger, a Brazilian-born Stanford graduate who shaped Instagram’s product and vision, was on the verge of decamping for his homeland. At the 11th hour his paperwork came through, and Krieger, along with co-founder and CEO Kevin Systrom, began to build Instagram into a social media giant with half a billion users and up to $50 billion in enterprise value. The company has also created hundreds of US jobs.

Now a pair of entrepreneurs-turned-investors, Nitin Pachisia and Manan Mehta, are trying to ensure that fewer immigrant-led startups face an untimely death by lack of visa. Two years ago they founded Unshackled Ventures, an early-stage venture fund and mentorship programme with a clever, market-based solution to the visa challenge facing many foreign-born entrepreneurs: In exchange for equity, Unshackled not only provides cash but also acts as an employer and visa sponsor for founders.

Their idea resonated in tech circles, and in no time Unshackled raised some $5 million from some 80 A-listers like Laurene Powell Jobs, Jerry Yang and Bloomberg’s venture arm. A larger financing round is said to be in the works.

“While our national dialogue around immigrants deteriorates, Unshackled’s model showcases the kinds of conversations that we ought to be having—conversations about removing impediments to opportunity, investing in extraordinary intellectual capital and spurring innovations that will benefit all of us,” says Powell Jobs in an email. “Unshackled rightly understands that immigrants represent nothing but potential.”

Obtaining visas for skilled immigrants is hard enough for tech giants like Google or Facebook. This year the US Citizenship & Immigration Services received 233,000 requests for the 85,000 H-1B visas available for skilled workers within a week of opening for applications. Securing one of those visas is especially hard for startups, which often lack the financing or wherewithal to show the government they’ll be able to pay an immigrant worker for a sustained period.

Pachisia experienced the visa challenge firsthand. Born in India, he came to Silicon Valley to work at a Deloitte consulting practice focussed on startups. He later ran strategy and finance at Kno, a well-funded startup. But when he came up with an idea for his own ecommerce venture, he found he couldn’t leave his employer, which had sponsored his visa, and was forced to moonlight, working on the startup on nights and weekends.

Mehta, who met Pachisia at Kno, was born in the United States, so he didn’t face the same issue. But his co-founder in a separate startup did. The experience brought Mehta and Pachisia back together, determined to “hack” the visa challenge for talented immigrants. After brainstorming the idea for Unshackled in a Palo Alto coffee house, they tested the waters with a website, a Facebook post and some fliers at Hacker Dojo, a co-working space for startups. Less than two months later they launched Unshackled. Their goal is to fund startups that over time will help create 100,000 new jobs.

Unshackled is hardly alone in tackling the issue. In August President Obama proposed a new rule that would grant temporary work visas to immigrant entrepreneurs who received a minimum of $345,000 from private investors.

The plan is something of a workaround to the “startup visa”, which would give visas to immigrant entrepreneurs—an idea championed by techies and embraced by the White House but stuck in congressional limbo. The proposal would make it easier for Unshackled entrepreneurs to obtain a visa, freeing Mehta and Pachisia to focus on their roles as mentors and company builders. “This country has an obligation to continue to attract the best and the brightest, and it needs to give them a reason to stay,” says Mehta, echoing what passes as gospel in tech circles.

As of now Unshackled has funded 15 companies, with founders from more than a dozen countries. Nine have gone on to receive additional funding, including one that is at the prestigious Y Combinator programme. While no Unshackled company has hit it big yet, none has failed, either—losing your visa is a powerful motivator.

—Miguel Helft

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)