Private Equity Giant KKR Goes Gentle

The barbarians who made billions pioneering Wall Street’s hostile leveraged buyouts now want to be Main Street’s go-to investor

Scott C Nuttall, one of the heirs apparent of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR) and the head of its global capital and asset management division, leans back in his chair while dining on the 42nd floor of the firm’s midtown Manhattan headquarters and shares a dream. “Maybe someday you will have private equity as a choice on your 401(k) retirement plan,” he says, eyeballing a turkey sandwich served on a plate of fine china (the firm caters lunch for the entire company every day). “Today, if you are a retired school teacher in California you can invest with KKR by virtue of a pension plan, but if you are a corporate executive managing your 401(k), you cannot. There’s no product available.”

Nuttall, 40, is in a hurry to change that—and change KKR in the process. He’s leading the charge to open the storied private equity firm to everyone. Barbarians at the service of the masses. Already, for as little as $2,500, you can invest in a KKR mutual fund managed by the same team that runs global credit funds for some of the biggest institutional investors in the country. For $25,000, you can invest in a KKR fund that buys distressed debt.

That’s a far cry from the $10 million or more qualified investors once needed to get into one of the firm’s 19 buyout funds, where their money could be locked up for more than 10 years and net annual returns fluctuated from a 1 percent loss to a 39 percent gain.

They’ve evolved a long way already. Nine years after it tactically diversified away from a single-minded focus on leveraged buyouts, $29 billion of KKR’s $74 billion in assets fall outside its legacy private equity business. Nuttall’s group, the firm’s fastest-growing division, with $25 billion under management, includes a global corporate bond and credit business, a so-called fund of funds, which allows investors to put money into a diversified basket of hedge funds and a proprietary trading desk picked up from Goldman Sachs in 2011. Since its inception in 2004, one of KKR Asset Management’s important high-yield strategies has logged an average annual return of 10.8 percent versus 8.5 percent for its relevant benchmark.

The biggest challenge Nuttall faces is gaining acceptance among individual investors and their financial advisors. KKR has never courted the little guy. Traditionally, the firm raised most of its capital from multibillion-dollar pension funds, banks, insurance companies and endowments. These institutional investors could—and did—thrive despite delivering mediocre returns. After all, they were playing with other people’s money, often at a great remove. Retail-level financial advisors, however, live and die by the very personal trust they earn by generating decent returns on their clients’ nest eggs. It takes more than a new wrapper on an old business to win over brokers.

Which is why, on a cloudy day last November, you could find Nuttall and one of KKR’s billionaire founders, George Roberts (net worth: $3.7 billion), shoulder-to-shoulder with Chuck Schwab, the patron saint of retail investors, at the brokerage giant’s annual conference held in Chicago’s McCormick Place convention centre. Before a crowd of more than a thousand independent financial advisors, the trio took to the stage to spread the gospel of investing Main Street savings with Wall Street titans.

Roberts, the ‘R’ in KKR and the founder known for his intellect and aloofness, even spent time manning the firm’s booth on the convention hall floor, mingling with frontline brokers. Why woo hoi polloi? Because that’s where the money is: “There are huge pools of capital there,” marvels Roberts, 69. “I talked to one fellow who managed $800 million and another who managed $5 billion.”

Numbers like that add up fast. In all, there is about $2 trillion managed by independent registered investment advisors, and that number is growing at a 13 percent annual clip, according to Cerulli Associates, a Boston-based financial research firm.

The numbers become even more enticing when you look beyond advisors to mutual funds and exchange trade funds, which can also be purchased directly by individuals. According to McKinsey & Co, by 2015 there will be $13 trillion invested in these types of funds, and 13 percent of this money will flow into so-called alternative assets, a category that includes many areas where KKR has deep expertise: Private equity, junk bonds and real estate. That 13 percent is more than double the amount that was allocated to alternatives in 2010.

The money is vital to keep KKR well capitalised, as the big pension funds it relied on for decades dry up and are replaced by tens of millions of Americans managing their own retirements through 401(k)s. “The implications for alternative asset managers are staggering because the bulk of all their money has historically come from pensions that are now going away,” says Josh Lerner, who teaches investment banking at Harvard Business School. “Over the next five to 10 years, individual investors are going to be a very important source of capital for alternative asset managers, and you’ll see them rethinking their business models.”

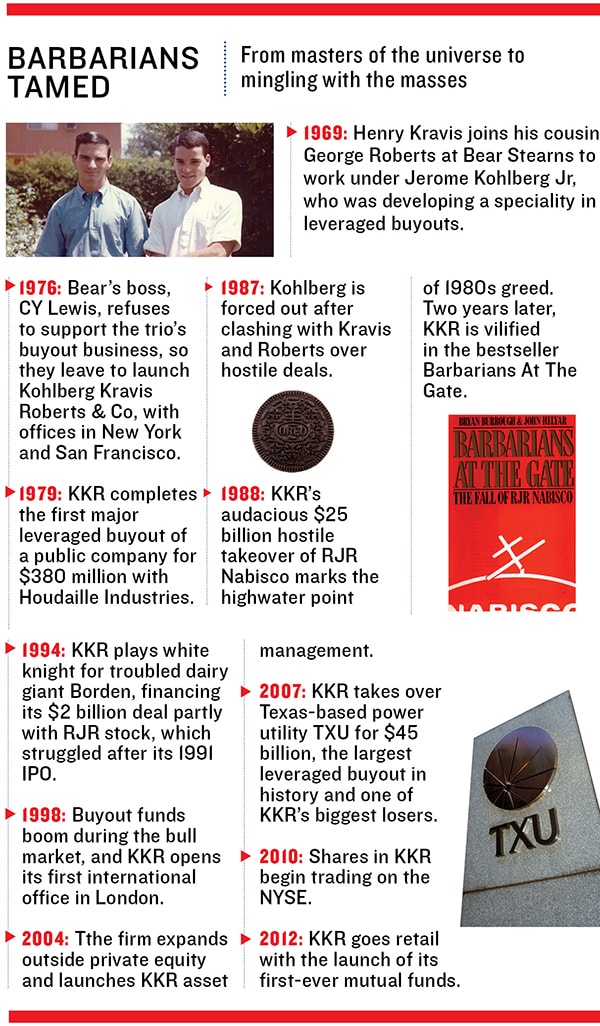

It’s all a long, long way from KKR’s roots. The firm was founded in 1976 by three Bear Stearns alumni: Jerome Kohlberg, who headed the corporate finance department at Bear, the brash Henry Kravis and his cousin Roberts, who were Kohlberg’s protégés. (Kravis was not interviewed for this article; Kohlberg was pushed out of the firm in 1987.) While at Bear, the three men pioneered friendly leveraged buyouts of public companies. The formula: Have management borrow money against the assets and cash flow of a company, and use that money to buy a controlling stake of it. The process left the companies weighted with crushing debt loads, which was thought to be good as it prevented management from embarking on wild spending sprees and ensured strict financial discipline (conversely, it also limited innovation and growth). Through a combination of cutting costs, selling assets and paying down debt, the now private firm could be brought public again, at a higher valuation, making a small (or large) fortune for the management team—and, of course, for Kohlberg, Kravis and Roberts.

KKR’s first fund was tiny—just $31 million, raised from Allstate Insurance, Citicorp Venture Capital and well-heeled individual investors—but it grew fast and made piles of money for its investors. In 1984, less than a decade after its founding, KKR raised its first $1 billion fund. By then, the firm was increasingly moving from friendly buyouts, to hostile ones, where new management would often strip the target company like a stolen car, sell off choice bits to the highest bidders and fire thousands of employees. In 1988, a year after Kohlberg left the firm, Kravis and Roberts engineered the ne plus ultra of hostile deals, the $25 billion highly leveraged hostile takeover of RJR Nabisco, immortalised in Barbarians at the Gate (Harper & Row, 1990). That deal generated nearly $1 billion in fees for KKR and its partners, but it proved less sweet for KKR investors, who squeaked out an 8.9 percent annual return in the fund that took RJR private. The takeover also resulted in the loss of at least 45,000 RJR Nabisco jobs. In all, during the 34 years between KKR’s founding and its IPO in 2010, the firm raised roughly $61 billion in capital, performed 185 buyouts, saw its portfolio companies shed tens of thousands of employees—and returned an average of 19 percent per year to its investors.

Now, the legendary raiders are donning the white hats. Besides the lure of trillions of dollars in fresh capital, the retail investment business holds another attraction for KKR and its shareholders—steady revenues from fees. In the case of KKR’s new junk bond mutual fund, the expense ratio is 1.31 percent. That’s puny compared to traditional private equity fees, but the firm can make up for it with massive volume: McKinsey & Co estimates that fees from alternative investments by mutual funds will surge to $25 billion in two years, up from $9 billion in 2010. “That’s $16 billion of revenues up for grabs,” says Nuttall.

And it’s the type of reliable revenue that Wall Street loves. Buyouts can be enormously profitable, but because the money is tied up for years, the returns are extremely uneven. In 2011, for example, KKR’s net income was $1.9 million on $724 million in revenues—a 0.3 percent profit margin. But, a year earlier, the firm made $333 million in profits on $435 million in revenues—a margin of 77 percent. Wall Street hates wild swings in earnings, and as a result KKR’s stock trades at an earnings multiple of around eight, far lower than the broader market. Compounding the sting: Steady-Freddy asset managers like T Rowe Price and BlackRock are awarded above-market multiples of around 20 times earnings.

“KKR and other private equity funds have a life cycle that’s lumpier than traditional mutual fund companies, which can constantly raise assets, generate fees, exist and grow for decades,” explains Robert Lee, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. To jumpstart its foray into the retail business, KKR is tapping its $6.5 billion balance sheet, including a $1.4 billion cash hoard, seeding its two mutual funds with $125 million, versus the typical $1 million seed at most mutual fund firms. But this is not a market that KKR can buy. Despite decades of experience and enormous Wall Street cred, it is a Main Street newbie. “They don’t have a manager with experience in a publicly traded mutual fund, but these guys are smart, so I’ll keep an eye on them,” says Brian Amidei, an investment advisor based in Palm Desert, California, with $600 million in assets. KKR has responded by recruiting Michael Gaviser from AllianceBernstein, who joined in November to build relationships with the likes of Fidelity and Pershing. “The things we’re doing in these new funds are things we’re already doing,” says Gaviser. “But now it’s structured in a wrapper for investors who want daily or quarterly liquidity.”

Roberts echoes the idea that KKR isn’t altering what he calls its “internal DNA”: “If you want to paint a picture of our firm, private equity will continue to be at the centre of it.” But he also admits that the makeover has been a long time coming. He distinctly remembers that in 2008, after the annual partners meeting, he gave attendees white T-shirts with two black circles on them, one tiny and one large. “The message was that the big black circle was our brain and the small black circle was what we were using of it,” says Roberts. The problem was KKR’s laser-like focus on leveraged buyouts was costing it huge opportunities. “If we went to see a company that didn’t want to do a private equity transaction we’d say, ‘Thank you very much,’ and we couldn’t do anything else with it,” Roberts says. The problem was so bad, Nuttall says, that KKR began maintaining a spreadsheet listing opportunities it had to turn down.

One still burns today. Williams Companies, a Tulsa, Oklahama Energy firm, was ready to be taken private by KKR’s private equity fund in 2002. But shortly before the announcement, Williams’ stock began to sink as one of its subsidiaries came under fire over shoddy energy trades. Instead of going private as planned, Steve Malcolm, Williams’ CEO, was calling KKR to help his company with at least $900 million in financing it required to avoid bankruptcy. In exchange, he offered KKR $2 billion in natural gas reserves and an 18-month secured note at 25 percent, plus warrants.

“We had to turn it down. It was very painful, but at the time KKR only had private equity funds and this was a credit investment,” Nuttall recalls.

“Ultimately, Warren Buffett made the investment along with a couple of hedge funds and generated something like a 30 percent or 40 percent return in 15 months.”

That’s not going to happen anymore. “We thought of ourselves as a private equity firm to that point,” says Nuttall, “when it became very clear that we are an investment firm.”

***********************

Debt-Equity Tango

KKR’s Indian arm wants to be present across the capital structure

By Shishir Prasad

KKR (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts) first came to Asia in 2005, and opened its India subsidiary, KKR India, four years later. While KKR is known for large buyouts in the US, the approach it has taken in building its Asia franchise is to hire a local team that can bring the best of KKR to that market while meeting the needs of the local market. The US-headquartered private equity behemoth has more than 80 companies in its portfolio and more than $60 billion of capital under its management. In India, its size is much more modest. Here, it has made around seven private equity investments and put little short of $1 billion to work.

In India, as in other Asian markets such as China and Vietnam, the KKR investments are for minority stakes in growing companies. In India, however, KKR is also focused on debt investments.

What’s a private equity company playing around with debt? Sanjay Nayar, CEO, KKR India, says he wants the firm to be present across the capital structure. That means if a company wants equity, debt or a mezzanine debt, KKR will provide it all. Nayar devised this approach because only offering a company an equity investment does not meet the need of many Indian promoters. “There are few buyouts in India. Good companies are not available for sale,” he says.

While this approach is not how KKR traditionally operates, Nayar and the KKR India team knew offering both debt and equity would work best in India. They understood that it was better for KKR to focus on providing various types of financing a company might need. “So we have done promoter lending, mezzanine debt, plain vanilla equity,” says Nayar. This approach of being debt-led also shows KKR as a solutions-provider to company owners. It may keep returns from being super-normal, as some critics of this approach say, but expectations for a debt investment are different from that of an equity investment.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)