How Jeff Skoll Plans to Tackle Poverty through Social Entrepreneurship

The former eBay president has put $1 billion behind a new kind of philanthropy, a brew that blends social entrepreneurship and the power of media to tackle poverty and any other problem that piques his interest

Four years ago, Jeff Skoll arrived on a small plane in the depths of the Brazilian Amazon region, just in time for the Waura people’s festival of the pique fruit, where he sipped from a bucket of its bitter, bright-yellow brew. The eBay billionaire was there to see work being spearheaded by Mark Plotkin and Liliana Madrigal, whose nonprofit, Amazon Conservation Team, was teaching the scantily-clad Waura to use a GPS to map their ancestral territory and carve out a protected area free from deforestation. “It’s the neatest thing,” says Skoll, his voice rising with enthusiasm. “It’s amazing to see these tribes that have barely been contacted, running around in war paint and living in mud huts, but with GPS they figure out how to go around on their land.”

Skoll was so pleased by the results of Plotkin and Madrigal’s efforts that last year his foundation gave $1.6 million to a project with Amazon Conservation Team and two other social enterprises that Skoll backs to use GPS and satellite mapping to create “conservation corridors” that will protect 114 million acres of the Amazon from deforestation. It’s a long-held goal for Plotkin and Madrigal, who have been working with indigenous tribes to protect the rain forest for nearly three decades. Skoll expects significant progress in three years.

There are thousands of people in the world like Plotkin and Madrigal, inspiring social entrepreneurs who dream up innovative solutions to pressing problems and then act on them. Jeff Skoll is their financier. As eBay’s first president, Skoll became a billionaire at age 33 shortly after the auction site went public in 1998. Like all good entrepreneurs, he was born with a knack for spotting the unmet need. Social entrepreneurs need money, media exposure and a network for collaboration.

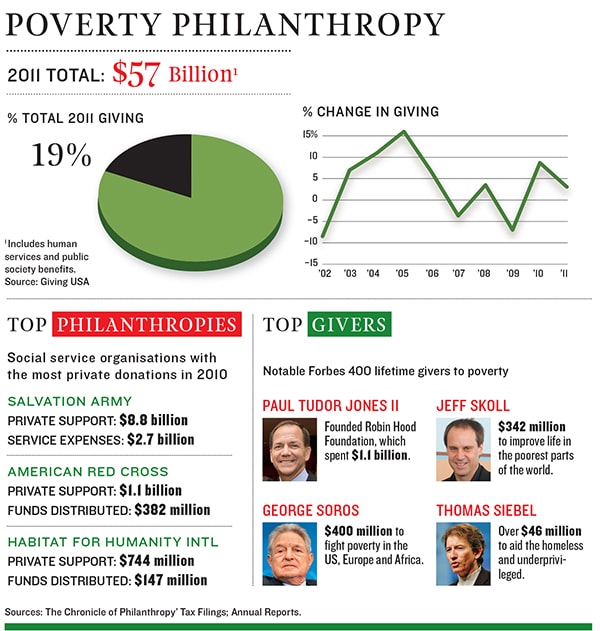

The Skoll Foundation has been providing all three since the days when social entrepreneurship was just an emerging trend. Skoll has given $342 million in grants to social entrepreneurs, more than any other funder. Before the Skoll Foundation, social entrepreneurs with a bit of a track record had a hard time raising money from big foundations because of their onerous paperwork, short-term funding and inability to abide changing plans along the way. Skoll understood as a web entrepreneur that money to effect big changes needs to be patient. “I wouldn’t quite use the term ‘mezzanine financing’, but in a way it is,” says Skoll. “Our financing is the ground between seed and some sort of exit.”

In just over a decade as a full-time philanthropist, Skoll can tick off plenty of successes. Due to the efforts of Skoll-funded groups, everyone in Gambia (population 1.8 million) has access to health care; deaths from water-borne diseases have declined by 85 percent in 700 villages in Orissa; 6,000 communities in seven African countries have declared an end to female genital mutilation; and thousands of rural poor with HIV in Haiti are getting treated with antiretroviral drugs. There are at least a dozen more examples. “We’re trying to change the equilibrium,” explains Skoll.

He wasn’t the first to invest in social entrepreneurs. Credit for that goes to Bill Drayton, who founded Ashoka in 1980. Ashoka has granted $97 million to date. Jacqueline Novogratz’s Acumen Fund has invested $75 million since 2001. What the shy, Canada-born entrepreneur with intense brown eyes and a slightly nerdy air has done is to amp up the appeal of his grantees by providing more money (there’s $930 million in dry powder at the foundation) and a new twist: He smartly exploits mass media to promote his social entrepreneur’s agenda. Matt Flannery, co-founder of online microlender Kiva, still gushes about how great it was for his then nascent nonprofit to be featured on the PBS show Frontline in 2006—thanks to the Skoll Foundation, which funded the production. The onslaught of microloans from people who saw the show was so great that it crashed Kiva’s servers for three days.

Skoll’s funding of social entrepreneurs often dovetails with his other line of work, running the five-time Academy Award-winning film production company Participant Media, which produced The Help, An Inconvenient Truth and Syriana. Its movies often pursue Skoll’s social agenda, but they don’t have to make money like regular studios, and that’s exactly the point.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation put $2 million toward an online social action campaign that accompanied Participant’s 2010 documentary Waiting for ‘Superman’, which examined charter schools and the failings of the US education system. The Gates Foundation is also co-developing with Participant a TV special on America’s great teachers that will air next year. “It’s terrific working with Jeff because of his innovative approach to doing good,” Bill Gates says in an email. Adds Ashoka founder Drayton: “Entrepreneurs are different—they’re about change. They can’t stop until they’ve changed the pattern,” he explains. “Jeff has never thought about a local solution.”

What drives a middle-class kid from Toronto (he’s now a US citizen as well) to spend a billion dollars-plus fixing the world’s problems? It starts with a dose of anxiety, the near-death of his father and the mores of the Jewish community in which he was raised. By the time Skoll had his bar mitzvah, he had heard countless times the phrase tikkun olam, a core Jewish ideal that means “to heal the world”. “Growing up with that, it gets built into one’s psychology,” Skoll says.

Skoll read avidly as a child. On camping trips with his sister and parents, he leaned towards Huxley and Orwell. “By a very early age, it had struck me that a lot of the trends in the world would be scary: Not enough resources to go around, terrible new weapons, potentially devastating wars,” he says.

He wanted to write books to get the message out about these dangers, but the pragmatist in him knew he needed to make money first. It turned out there were limits to how much of a priority money would be. His father was diagnosed with kidney cancer a few years before he entered the University of Toronto for an electrical engineering degree. Skoll Sr sold his industrial-chemicals business to his business partner for not a lot of money and moved to the Caribbean. “My dad always wanted to sail. They lived on a boat for eight years,” says Skoll. “He said something at the time that was very influential. He said he was afraid he hadn’t done the things he wanted to with his life. That was really a wake-up call.”

Skoll worked his way through university pumping gas; in 1987, he started a computer rental company, from which people kept stealing computers. An attempt to do systems engineering consulting did better but wasn’t a hit. “I realised very quickly that I had no idea what I was doing,” he says. He left Canada for an MBA at Stanford and, through friends in Silicon Valley, met Pierre Omidyar. Omidyar approached Skoll in 1995 about creating an online auction company. Skoll told him it didn’t sound like a good idea. Not long afterwards, Omidyar told him revenue was doubling every month and he needed help. Skoll was eBay’s first employee and first president. He took charge of the back-end of eBay operations, wrote the business plan and helped with hiring to keep up with the torrid pace of growth. Three years later, Skoll became a billionaire soon after the IPO. “All of a sudden, I not only had the money to start to write the stories, but I realised I could do other things with it,” he says. He started eBay’s foundation with just a few million dollars.

In 1999, he created the Skoll Foundation with $34 million. It was a part-time effort, making ad hoc grants. A skiing accident that year left Skoll with his back so badly hurt he couldn’t sit down. Throughout 2000, he took meetings lying on a conference table. The discomfort was a big reason for leaving eBay in January 2001. Now, he could focus on expanding his foundation quickly.

Skoll hired Sally Osberg, the founding executive director of the Children’s Discovery Museum of San Jose, California, to run his foundation. When they went to see her mentor, John Gardner, Lyndon Johnson’s Secretary of Health, Education & Welfare and before that president of the Carnegie Foundation, his advice was to “bet on good people doing good things”.

Skoll and Osberg heard from entrepreneurs that they were having difficulty getting past the early stages. Skoll streamlined the process: Offer grants with minimal paperwork, supply three years of funding and deliver help on media and strategic advice. To improve the business skills of social entrepreneurs, Skoll pledged $8 million in 2003 to create the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship at the University of Oxford. The foundation pays for five entrepreneurs a year to take MBA classes. These Skoll Scholars also run an annual forum where many of Skoll’s entrepreneurs end up cutting deals. Says Andrea Coleman, co-founder of African health care nonprofit Riders for Health, a 2006 awardee: “Sometimes, we think we should just fundraise for these other amazing people.”

The Skoll Foundation gets over 250 applications a year and makes four to six grants. Skoll and Osberg developed a rigorous application system, starting with an eligibility quiz. Applicants have to line up with one of their causes. And the timing has to be right, with requirements such as a lack of civil wars raging in your country.

Ann Cotton runs the Campaign for Female Education, or Camfed, a UK nonprofit that has helped 1.7 million children in five African countries attend school. Skoll grants of $3.6 million since 2005 helped Camfed expand its programme from 10,700 girls a year to 25,400 girls, as well as attract larger multimillion-dollar donations from the MasterCard Foundation and the UK Department for International Development.

Three years ago, Skoll pledged $100 million to the Skoll Global Threats Fund, which tackles the knottiest of problems—pandemics, climate change, Middle East conflict, nuclear weapons and water—through supported advocacy groups. With the Rockefeller, Packard, Hewlett and other foundations, Skoll set up Climate Nexus, a swift-response team that fact-checks media reports and research studies on global warming. The fund is backing improved efforts globally to test for pathogens and detect outbreaks more quickly.

There’s plenty more that Skoll wants to do. He has been living in Beverly Hills for seven years but over the summer moved back to Silicon Valley with his girlfriend, Stephanie. He’s hoping to have kids and wants to leave them some of his fortune but not a lot. In 2010, Bill Gates called and asked Skoll to sign the Giving Pledge, and Skoll easily said yes. “If I die today,” he says, “everything goes to the foundations.”

Image: Dale Robinette / HO / EPA / Newscom

Jeff Skoll, using money, media and an empathetic mind to change perceptions on as big a scale as possible

Hollywood’s Agitprop Shop

Jeff Skoll knows how to host a movie screening. He spent eight days in August in Israel and the West Bank and, while in Ramallah, took an afternoon to show the new documentary State 194, about Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s efforts to achieve statehood for Palestine. The film was financed by Skoll’s Participant Media. The audience? Salam Fayyad himself. When it was over, Fayyad went around the table, offering a plate of sweets to his guests. Says Skoll, “He was effusive in his praise.”

Skoll, a reform Jew in favour of a two-state solution, sees Fayyad as a hero. “If people see the movie, instead of thinking violence and terrorism they’ll think these people are human, trying to make the best of a bad situation,” he says. This is typical Jeff Skoll, using money, media and an empathetic mind to change perceptions on as big a scale as possible. Skoll’s Participant Media, launched in 2004, is the go-to Hollywood studio for issues-driven filmmakers. It has financed 39 films and garnered 22 Academy Award nominations, including an Oscar for best documentary for Al Gore’s ominous An Inconvenient Truth. Yet, its biggest hit so far was hardly controversial. That would be The Help, a civil-rights-era drama that grossed $212 million worldwide. But Skoll says he has no plans to cash in by watering down the politics. How well a film does at the box office isn’t the main concern. “We like to be break-even if we can, and we have been. Our other bottom line is social change, and that’s where we really look to make an impact,” he says. He tells Forbes he’s close to buying a US cable-TV channel to reach an even bigger audience and is looking to expand operations to China, Europe and Latin America.

After seeing Participant’s 2008 food-safety documentary, Food Inc, more than 230,000 people signed a petition requesting that Congress reauthorise the Child Nutrition Act, which was passed in December 2010. Skoll hosted nearly 100 screenings of the nuclear-arms-race documentary Countdown to Zero for groups including the CIA, the Kremlin and decision-makers in India. The grassroots campaign that accompanied the film targeted US senators whose votes were needed for the New START Treaty, which the US Senate ratified in December 2010.

—KD

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)