Dursts and their eventful journey to the World Trade Center

The tallest, most meaningful building of this American century, the new World Trade Center, is about to open. Risks abound for everyone involved, except the billionaire Durst family, who initially opposed the tower—and now sit on a sure thing

Douglas Durst stands 80 floors above the place in Manhattan that is known less and less as Ground Zero and more as One World Trade Center, a 1,776-foot symbol of American pride and the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere. He can see across the length of Manhattan, then over to New Jersey and then east, all the way to Greenwich, Connecticut. One hundred feet below, a helicopter looks like a child’s toy.

The mind-numbing views come with a catch: Precious few people are signing up to enjoy them.

Since the Durst Organisation stepped in three years ago to manage the building and leasing of New York’s symbol of post-9/11 recovery, only six tenants have signed up for space. Come November, when the building opens and magazine publisher Condé Nast moves in, the tower will be just 60 percent leased, Durst says. To boost that dismal figure, the asking price for the tower’s middle floors recently dropped by 10 percent, to $69 per square foot.

For the port authority of New York & New Jersey and the citizens of those two states that ostensibly control it, that’s bad news: By latest count, it’s shelling out nearly $4 billion to build One World Trade and $10.8 billion more to develop the rest of the site. For the Dursts, it doesn’t matter much. They have a 10 percent equity stake in the tower and a 99-year contract to run and lease it—all with little financial risk. Whether the building rents out next week or several years later, they win in the end: One World Trade will provide steady, solid revenue for future generations of their family real estate business, while growing in value at the same time.

Savvy deals like this have made the Dursts one of New York City’s great real estate dynasties, worth a collective $4.4 billion, according to Forbes, thanks to a real estate portfolio that includes 11 Manhattan skyscrapers, such as One Bryant Park, the third-tallest building on the island at 1,200 feet. Douglas’ grandfather created the Durst Organisation nearly 100 years ago; his father, Seymour, built the family’s first skyscraper; Douglas played a major role in reshaping Times Square and now One World Trade. Frequently described as eccentric, some of the 33 family members who control this empire have varied interests: Seymour was obsessed with the national debt, so he built a giant illuminated National Debt Clock near Times Square; Douglas, an environmentalist, owns an organic farm; Anita, his daughter, a former avant-garde actress, provides free studio space in family and other buildings.

The family shares another trait: a professed disdain for wasteful government spending and market intervention—and an uncanny knack for profiting from it. In 2007, when the “Freedom Tower” was still a messy hole in the ground, Durst and Anthony Malkin (whose family controls the Empire State Building), took out a full-page ad in New York newspapers, urging governor Eliot Spitzer to slow construction down. Their argument: The port authority should wait to build the most important tower until the four other towers were complete, so that One World Trade might capitalise on the others’ success. Durst and Malkin also railed against a plan (one that was jettisoned) to house government agencies in One World Trade: “Why, now, is the government planning to pay for the construction of an overly expensive design to be occupied by government agencies at overly expensive rents, all at the expense of taxpayers’ money which could be put to better uses?”

But when politicians plowed ahead, Durst won the contract to run the building. And why not? “I was against it before it was built,” admits Durst. “If there’s going to be subsidies handed out, they should come our way.”

The Durst’s family tale begins with Joseph Durst, a tailor, who travelled from what is now Poland in 1902 and arrived in New York with three dollars. Within a decade, he was a partner at dressmaker Durst & Rubin. The family legacy first took shape in 1915, when he bought his first building, in Manhattan’s Garment District.

Joseph and his wife, Rose, had five children; three followed their father into the family business. Seymour, the eldest, moved the Dursts into skyscrapers, buying up small parcels under assumed names to eventually create blocks of land ripe for major development.

“He had an incredible amount of courage when it came to putting real estate together,” says Jerry Speyer, one of the two founding partners of New York’s Tishman Speyer, the real estate company that controls Rockefeller Center and the Chrysler Building.

Seymour’s personal life was touched by tragedy: In 1950, his wife, Bernice, then 32, plunged to her death from the roof of their Scarsdale home, leaving behind four children (Douglas, the second child, was just 6). Seymour never remarried, pouring himself into real estate and his many hobbies, including protests against unnecessary government encroachments.

To this end, he formed the “Committee for a Reasonable World Trade Center,” fighting the Port Authority’s development of the tract his family now runs. In 1968, the committee took out a full-page advertisement in the New York Times, depicting the Twin Towers with a now-chilling rendering of an airplane heading for the skyscrapers’ upper floors. The point was to criticise the towers’ potential interference with flight navigation and television reception. Of course, they had other reasons for fighting the project. While now wistfully cherished, in the early 1970s, the World Trade Center was 10 million square feet of government-funded office space that was dumped into the New York market—just as the city slid into a bitter recession.

Their fight against the Trade Center foreshadowed an even bigger public battle. Durst was among several prominent developers who had quietly rolled up dozens of parcels throughout Times Square. Some of his tenants were a seedy lot, including peep show operators, “massage parlours” and purveyors of other vices. By 1984, one single block on 42nd Street was generating 2,300 crimes a year.

As with the World Trade Center, a quasi-governmental entity tried to change the game—dictating a $2.6 billion redevelopment, powered by $240 million in tax abatements granted to a different real estate kingpin, George Klein. Once again, the Dursts went to war, filing three lawsuits, allegedly funding more than 40 others (the Dursts denied it) and inflaming the court of public opinion. (“Perhaps all that new office space will simply provide more consumers for the drug trafficking and other illicit activities that now characterise one of the most notorious blocks in the world,” wrote Seymour in a 1988 op-ed.) Helped by the poor economy, in the end, they managed to stall redevelopment for most of the 1980s.

Then, in 1994, with the real estate market blooming, they pounced. Douglas bought the development rights from Klein—one of the city’s appointed developers and a target of a Durst lawsuit—picking up $100 million of the very tax breaks that the family had vigorously protested. “Yes, it’s ironic,” Durst told the New York Observer. “But we didn’t put the tax breaks in place. If they’re there, we’ll use them.” Four Times Square, smack on 42nd Street, was the family’s biggest project, and Douglas’s baby (Seymour died in 1995, with Douglas as the clear successor). He landed Condé Nast, which had previously been on Madison Avenue, as the anchor tenant, and the Disneyfication of Times Square moved apace. “It’s an amazing family,” says Steve Spinola, president of the Real Estate Board of New York since 1986. “Are they controversial? I think if you’re not controversial, you’re not good at what you do.” After that building came online in 1999, the Dursts moved their efforts to a bundle of lots they owned next door. Bank of America approached the family, hoping to build a corporate headquarters, financing half the construction and agreeing to occupy most of the building. The Bank of America Tower at One Bryant Park, a $2 billion, 51-storey skyscraper, was the first in North America to achieve LEED platinum certification, complete with composting on the roof, high-tech air filtration systems and its own heat-and-power plant. By 2010, when the tower was completed, the Dursts were lords of 10 million square feet of Manhattan office space and 1.5 million square feet of residential rentals—all with less than 30 percent debt in an industry where 50 percent is considered conservative.

Then came the chance to reshape a national icon—the one they’d been railing against for over 40 years.

Six weeks before September 11, 2001, New York City developer Larry Silverstein signed a $3.2 billion, 99-year lease with the port authority for the Twin Towers. His rent was $10 million a month—as long as his tenants paid more than that, he’d turn a profit.

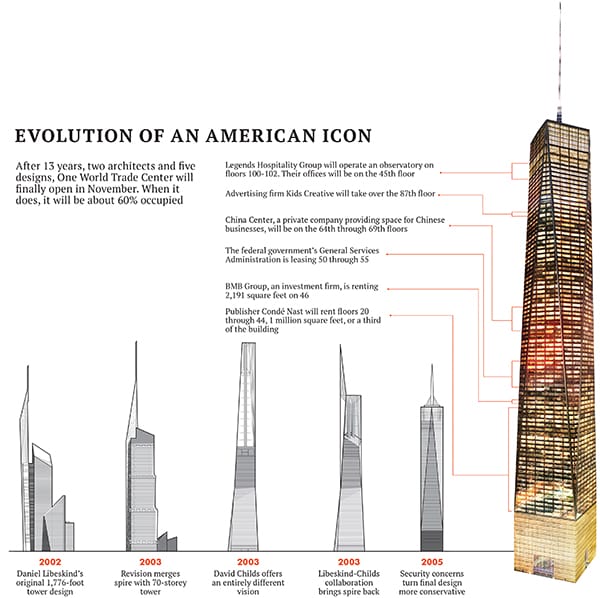

When the towers were destroyed, he was left with a gaping $120-million-a-year hole—and extraordinary influence, due to an eventual $4.6 billion insurance payout, over the plans for redevelopment. Polish- born architect Daniel Libeskind drew up a master plan for five new towers, including a single new One World Trade standing a symbolic 1,776 feet high. But the project quickly turned into a boondoggle, with two architects (Libeskind, then David Childs, Silverstein’s personal pick), 25 government offices and a host of politicians all weighing in. “Work stopped for one year due to disagreements,” says Libeskind.

Groundbreaking finally took place on April 28, 2006. By November, Silverstein was out as developer. Even with the insurance money, he didn’t have the money to build. The port authority convinced then governor George Pataki it could do a better job and paid Silverstein $21.5 million to go away.

It’s hard to think of a more difficult construction project. Not only is the site on hallowed, emotionally charged ground, its technical issues are massive. To prep the foundation, for instance, workers had to dig by hand, with picks and shovels, to avoid disrupting a New York City subway line and the path train to New Jersey. For years as the underground work went on, it looked to passersby like no progress was being made. All the while the costs went up. In 2008, then governor David Paterson appointed a new port authority chief, Chris Ward, who made one of the few good decisions stemming from Paterson’s feeble tenure. “We knew that the port authority’s skill set was not going to be developing the largest and most expensive office tower in America,” says Ward, who left the agency in 2011. Under his direction, five developers were invited to bid on the project. The Dursts, the bane of every World Trade Center proposal for decades, won.

Why? They came up with the most advantageous financial arrangement, linking their management fee to cost savings for the port authority, says Ward. And while the port required all bidders to put in $100 million for an equity stake in the building and agree to a 99-year contract, the Dursts sweetened their offer with a strategy they’d pioneered in past deals.

While the four other bidders offered a traditional fat management fee plus equity stake, the Dursts offered a “floating” valuation, where value of their ownership stake won’t be determined until 92 percent of the tower is leased, or 2019, whichever comes first. That pushes them to get tenants in faster and at higher rates. It helped them clinch the deal.

“The reason they were chosen was to leverage a credible private sector developer who would put skin in the game,” says Scott Rechler, a Port Authority commissioner who oversees the Trade Center. Douglas Durst says they had the financial muscle, the manpower and the expertise to give the port what it wanted. “We put ourselves in the other side’s position and craft what works for them.”

By the time the Dursts stepped in, the skeleton of the tower was mostly built, but the family shaped its final form. Their management fee for overseeing the last phases of construction included a fat $15 million plus 75 percent of any cost savings up to $24 million and a declining percentage for cost savings gained beyond that. Incentivised, they took out the axe. They are already most of the way to their cost-savings benchmark: The Dursts have nabbed $14.5 million from changing items like venting out the side of the building instead of the top and getting rid of the stainless steel steps on the plaza. Meanwhile, they’ve pushed the port authority to give them a cut of the savings from nixing a high-tech skin for the 408-foot spire on top of the tower. A raw look, the Dursts insisted, exposing the antenna and broadcast equipment inside, would suffice. Some easy money made, the Dursts moved on to the long game. Under their deal with the port for the next century, every time a new tenant signs, the Dursts get 8 percent to 13 percent of the first year’s rent. That makes One World Trade a low-risk bet that will provide subsequent generations with a steady source of revenue. Especially when your other buildings funnel you a constant supply of tenants. Their first move: Bringing over the anchor tenant from their Times Square building, Condé Nast, which is renting 1 million square feet of office space—one-third of the tower. A quick score for the Dursts and a sweetheart deal for Condé Nast, which scored rent down to a reported $60 per square foot where similar space in Midtown leases for upwards of $75 a square foot. Says John Bellando, COO and CFO of Condé Nast, “We’ve had a very solid relationship with the Dursts.”

The Dursts also happily accepted the kind of government tenant they’ve often derided—in this case the General Services Administration, which took 270,000 square feet. Beyond that, the Dursts landed just three new private tenants amid security concerns and a sluggish economy. With those five tenants, plus a hospitality group to operate the three tourist observation floors, the building is 56 percent leased. The annual management fee for operating the building isn’t particularly lucrative—at 65.5 cents per square foot, it’s only worth about $2.1 million this year. But it’s an annuity that will tick up each year and something the Dursts can easily absorb with scale and manpower, while burnishing the family brand. As for their $100 million investment for some 10 percent of the building, they expect it to pay in just a few short years, when One World Trade is fully leased and worth upwards of $2 billion.

“Over the long term, for the next 20 years, it’s a very low return for us,” says Douglas. “But we always have a long-term outlook.” And they get what they want in the end.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)