David Caldwell and his magic touch

A dozen years ago touchscreen pioneer David Caldwell narrowly missed a chance to revolutionise consumer electronics. Can his latest invention bring redemption?

In the early 2000s, engineer David Caldwell might have missed the chance of a lifetime. While developing touch-sensitive switches for home appliances, Caldwell was invited to Cupertino, California to demonstrate his patented TouchSensor technology to Apple, which was looking to replace the mechanical scroll wheel in the original iPod. After peppering him with questions about how it worked, an Apple engineer asked, “Can you integrate it into a round wheel?” Sure, replied Caldwell.

But nothing ever came of the discussion, partly because Illinois-based Gemtron, the glass company that controlled his technology, wasn’t interested in diversifying beyond its core expertise: selling $100 cooktops embedded with electronics to companies like General Electric, Whirlpool and Electrolux. Apple, of course, found another way to make its touch wheel. Some 400 million units and $67.5 billion in sales later, it is still in use on the iPod Classic.

Who knows what might have happened if the talks continued? Caldwell, now 58, his round face framed by shaggy bangs and rectangular glasses, tries not to dwell on the missed opportunity. “You can’t look back,” he says, sitting in a nondescript office-park laboratory in Michigan. “I did okay.”

Caldwell holds over 30 patents, many on touch technology. His TouchSensor switches have been incorporated into millions of control panels, for everything from automobiles to washing machines to beverage dispensers at fast-food joints. Still, when Gemtron sold TouchSensor to another firm in 2007 for just $65 million, Caldwell opted to strike out on his own. Less than a year later he formed a new company, AlSentis, to reinvent touch technology once again.

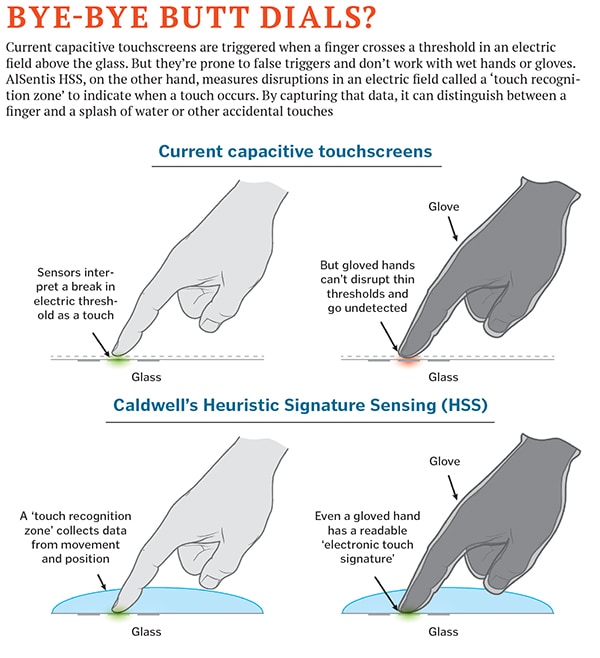

The result, eight years later, is a potential breakthrough that could transform how people interact with their electronic devices. Called HSS (Heuristic Signature Sensing), Caldwell’s patented setup is more reliable and uses far less energy than today’s touch systems. It even works when wet or dirty, and can be operated with gloves on. “From what I’ve seen,” says Bruce Banter, president of Tech-D-P in Plymouth, Michigan, an expert in automotive touch controls, “there’s nobody even close”. Most touch-sensitive products, like those used in the iPhone, are ‘capacitive systems’. They sense when and where an object—typically a finger—breaks an electric field. To trigger a touch signal, engineers set a very thin threshold, just above the surface of the device, to measure capacitive change. That’s why a light touch is all that’s needed to operate a smartphone. But environmental factors can wreak havoc with capacitive systems: Who hasn’t accidentally butt-dialled someone or struggled in vain to make a call with wet hands or with gloves on?

Caldwell’s breakthrough idea: Do away with the arbitrary trigger point in a capacitive system and replace it with a smarter electronic ‘touch signature’ that can detect an actual touch. HSS technology uses a larger area above the surface—the ‘touch recognition zone’—to capture and process more information from the electric field. HSS measures not only when an object (or finger) breaks the field, but also the speed at which the object is travelling, when it stops and its final co-ordinates. By quickly processing all the extra data, it knows when a finger is a finger and when it’s a drop of water (no more butt dials). It’s not dependent on calibration of an arbitrary threshold, and hence works with gloves.

For now, AlSentis is focused on licensing its technology to replace buttons on cars, industrial equipment and kitchen devices. Touchscreen prototypes for consumer devices are coming later this year. On the new Chevrolet Corvette and Camaro, General Motors replaced the little blue OnStar button on the frame of its cars’ rearview mirror with an HSS switch embedded directly into the glass for a sleeker look. Bauer Products redesigned its keyless entry systems for recreational vehicles using HSS sensors because the old LED-backlit keypads were prone to malfunction when it rained.

“Think of all the controls, light switches, machinery, dashboards in cars. We’re really excited,” says Amway heir Rick DeVos, who is an AlSentis investor through Start Garden, his early-stage venture firm (other investors include Windquest Group and Methode Electronics). The auto industry alone produces 4.6 billion buttons a year. Coca-Cola has millions of vending machines in the US, each with eight to 12 buttons.

After graduating in 1975, Caldwell joined the Navy, where a recruiting test pegged him to work on a nuclear-powered vessel. He made the most of it, learning all he could about energy, electronics and microprocessors. When he left the Navy in 1981, he married and settled in Michigan, working on rain-sensing windshields for General Motors. He later jumped to GM supplier Donnelly, where his interest in thin film sensors took off. But Donnelly was less interested, so Caldwell left. He created a new company, TouchSensor Technologies.

Finding capital was a struggle. His father provided the original seed money and Caldwell had to scramble to find out-of-state investors (he found none in Michigan), eventually selling control to Gemtron to stay afloat.

AlSentis is his second chance. The company says it broke even last year as revenue exploded from $123,000 in 2013 to more than $2 million in 2014. The company’s business model is to license the technology and outsource manufacturing. It hopes to raise several million dollars this year in a Series A financing round.

“This is so much bigger than TouchSensor,” says Caldwell. “There are so many applications that want touch. Where we’re standing, the road is wide open.” And who knows? Maybe someday it will lead back to Cupertino.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)