Can Venture Capital Save The World?

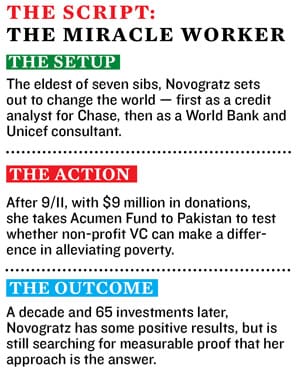

Jacqueline Novogratz and her Acumen Fund attack the human race's oldest problems with a groundbreaking model: Fund noble startups and let altruistic capitalism do the rest

Bahawalpur in eastern Pakistan is known for magnificent palaces built during the British Raj, but in the dusty part of town where most of the 400,000 residents actually live, four dozen farmers have gathered in the decidedly unpalatial concrete building that houses the local branch of the National Rural Support Programme Bank. Their darkened, sun-creased faces testify to the toll of tilling soil in one of the hotter places on Earth.

Suddenly the front door swings open and a tall woman with piercing blue eyes and brownish blonde hair struts in. Accompanied by the bank’s president, Rashid Bajwa, Jacqueline Novogratz whips out her red notebook and gets down to business. “What kind of livestock do you have?” she asks one client. “How much money are you saving at the bank? What do you do with that cash?” An hour later, the notebook now filled with minute details of how, exactly, the farmers intend to pay back their loans, as well as whether their daughters go to school and what they want their children to do when they grow up, Novogratz walks out of the bank, satisfied. “I’m feeling optimistic about rural Pakistan,” she tells me. “Farmers are making good money.”

Novogratz plays the role of auditor because, as CEO and founder of the Acumen Fund, helping people starts with financial due diligence. In April, Acumen sank $1.9 million into the bank in exchange for an 18 percent stake, one small investment in a decade-long experiment in charitable giving. Instead of shovelling aid dollars to causes or governments that give away life-sustaining goods and services, Acumen espouses investing money wisely in small-time entrepreneurs in the developing world who strive to solve problems, from mosquito netting to bottled water to affordable housing. It’s a new twist on the old adage about teaching a man to fish, except that Novogratz wants to build an entire fish market.

The bank in Pakistan is a good example: Acumen’s financial injection has enabled the bank to lend small amounts (up to $350) to farmers. Acumen has given Pakistani farmers the ability to access cash at credit card rates, versus the loan shark terms of before — a staggering 125,000 clients have tapped the bank for $30 million in new credit this year. Novogratz’s infusion has also allowed the bank to take deposits for the first time, introducing the idea of savings, and 6 percent interest rates, to a community that has been locked in poverty for centuries. Since April, 10,000 farmers have deposited $7 million in the bank, which of course, has resulted in yet more loans.

Novogratz obsesses over such numbers. Hence, the signature notebook. Field visits, says the 50-year-old Novogratz, “give me insights and quantifiable data I can bring to conversations that have, frankly, been devoid of them for so long.”

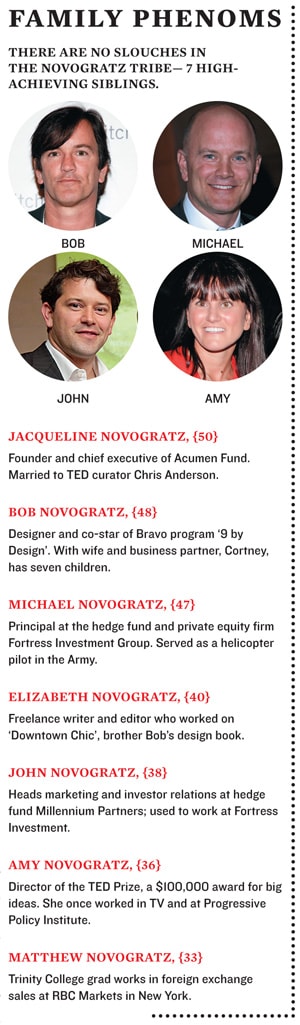

Quantification is key. Acumen Fund is quite literally a philanthropic venture capital fund, which has put $69 million to work in India, Pakistan, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda. Its loans and equity investments mandate the same benchmarks traditional VCs use, with a twist: Since the donor-investors don’t get their money back — all returns are reinvested in Acumen — progress is measured not in ROI but rather against the good that could have been done by simply giving the money away. No easy task but one that makes Acumen’s mission more critical: To prove that altruistic capitalism can solve the world’s ills. Even in a dazzling clan of overachievers, Novogratz precociously stood out. Jacqueline’s six younger siblings include 48-year-old Bob, a designer and co-star of Bravo’s 9 By Design, and 47-year-old Michael, a principal at the hedge fund Fortress Investment Group. “By the time she was four years old I realised she was different,” says Novogratz’s mother, Barbara, who ran an antiques business while her husband, a West Point grad and US Army major, served in Korea and Vietnam. “I knew she’d always be involved with people and try to help them. When Jacqueline was little her father would send letters back from Korea. They talked about poverty. She would ask, ‘Why are they poor?’” Brother Bob remembers his perfectionist big sister as “very Marcia Brady”, the girl who sold the most scout cookies, got the best grades and worked all night on projects: “She was always hell-bent on changing people’s minds about the world at a young age.”

Even in a dazzling clan of overachievers, Novogratz precociously stood out. Jacqueline’s six younger siblings include 48-year-old Bob, a designer and co-star of Bravo’s 9 By Design, and 47-year-old Michael, a principal at the hedge fund Fortress Investment Group. “By the time she was four years old I realised she was different,” says Novogratz’s mother, Barbara, who ran an antiques business while her husband, a West Point grad and US Army major, served in Korea and Vietnam. “I knew she’d always be involved with people and try to help them. When Jacqueline was little her father would send letters back from Korea. They talked about poverty. She would ask, ‘Why are they poor?’” Brother Bob remembers his perfectionist big sister as “very Marcia Brady”, the girl who sold the most scout cookies, got the best grades and worked all night on projects: “She was always hell-bent on changing people’s minds about the world at a young age.”

From there, Novogratz’s narrative gets almost hagiographic, full of absurdly perfect coincidences and anecdotes. She put herself through the University of Virginia, with a double major in economics and international relations, by tending bar and doing three part-time jobs. Then came the interview at Chase Manhattan Bank in which, asked if she wanted to be a banker, Novogratz replied she was only appeasing Mom and Dad, who wanted her to go through the motions “just for practice.” A pity, her interviewer replied, because she would’ve been able to visit 40 countries working for the bank. In a do-over that seems inconceivable, she answered the question afresh, declaring that she’d craved the life of a banker’s since she was a kid — she got the job, learned finance and, at age 22, started flying first-class around the world, reviewing the quality of loans, especially in troubled economies.

After three years of travelling to countries like Brazil, where “throwaway people” had no access to commercial credit, Novogratz had a showdown with her boss over her idea of extending small loans to the working classes. She later quit and moved to Africa, where she consulted for the World Bank and Unicef, mainly in Rwanda, and helped found Duterimbere, the nation’s first microfinance bank.

Then, another seminal, if extraordinary, coincidence. As a girl, Novogratz had been given a blue sweater by an uncle. She wore it constantly until, as an adolescent, she grew tired of being teased about the mountains embroidered across her chest; into the Goodwill bin it went. Now, while jogging one day in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, she came across a boy wearing the very sweater — confirmed when she accosted him and looked at the name tag. Her road-to-Kigali moment she took as a sign, as she writes in her 2009 memoir-cum-PR campaign, The Blue Sweater: Bridging the Gap Between Rich and Poor in an Interconnected World, “to understand better what stood between poverty and wealth.”

One early approach, decades before Acumen, was microfinance: Muhammad Yunus’s earliest efforts in Bangladesh go back to the mid-1970s. But armed with Wall Street know-how and $8 million from the Rockefeller and Cisco foundations and three private donors, Acumen launched with its pioneering venture capital model in April 2001. The focus was health technology, at least until 9/11. After the attacks she convened a group of foreign policy experts to explain fundamentalist rage. Discussions turned to Pakistan, a geopolitically significant cauldron of anti-Western feeling. Asked by one of the assembled what she would do with $1 million, Novogratz said she would travel to the Muslim world and create institutions that “provide a sense of hope and possibility for those countries and the rest of the world.”

Weeks later Novogratz fortuitously got two anonymous gifts of $500,000 each and took her first trip to Pakistan in January 2002. Acumen has since invested $13 million there in 12 businesses. She has also collected $2.7 million from 40 Pakistani donors and travelled to that country 20 times, turning one of the most volatile, anti-American populations into a vibrant experiment in alleviating poverty.

An entire non-profit venture capital industry has sprung up, firms like Bamboo Finance, Grassroots Business Fund and Small Enterprise Assistance Funds that all prefer the term “impact investors.” The Omidyar Network, launched in 2004 by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar and his wife, Pam, has invested $450 million in equity and grants to promote microfinance, entrepreneurship, technology and government transparency, mostly in developing countries.

Much of this action stems from Novogratz’s ability to draw attention — and donor dollars — to this approach. And indeed, by traditional venture capital measures, the Acumen Fund has done pretty well in its first decade: Of the 65 businesses funded so far, three have bought back their shares from Acumen, 11 have repaid loans and 10 are profitable. Five companies have been written off, versus the 50 percent a typical venture capitalist will bury.

The difference is that VCs are happy to offset a high percentage of losers with home runs — one Facebook or Google seed investment swamps a dozen dogs. While Novogratz’s good investments don’t work that way, there has been a payoff. A recent report by the Global Impact Investing Network, a Manhattan non-profit focussed on making impact investing more effective, collected data from 463 organisations from 58 countries in 2010. The report claims their efforts resulted in 23,355 jobs at portfolio companies that generated $1.4 billion in revenue by serving nearly 8 million people.

“I would say that at the broadest big-picture level, we’re optimistic this can make a big difference,” says Michael Kubzansky, a partner at Monitor Group in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who has studied impact investing and spearheaded two comprehensive studies of market-based approaches in India and Africa. Key, he says, is getting the business model right, whether it’s providing cheap private education or contract farming. Success requires time and what Novogratz calls “patient capital,” which has a longer horizon than most antsy private investors are willing to give. Says Kubzansky: “It can succeed on a large scale and provide significant increase in income for those participating.”

Many in the field want to take this a critical step further, to be able to measure societal impact beyond the number of lamps sold or low interest rates issued or income produced. That means assessing if those lamps have led to greater productivity and increased wages — and helped lift people out of poverty.

That’s a complicated yardstick. Global Easy Water Products of Aurangabad, India, which sells drip irrigation devices, is considered a win for Acumen because it is profitable (but will not release numbers to Forbes) and has boosted farmers’ income and crop yield and delivered savings in utility costs. Other successes are even tougher to pinpoint. D.light Design has sold 1 million solar-powered devices, mostly in India, and claims it “will have improved the quality of life for 50 million people” by 2015 but won’t share any financials with us. A to Z Textile Mills, which sells mosquito bed nets, depends on a giant customer: the Global Fund. “Is that a long-term risk?” Novogratz asks rhetorically. “No doubt. But in terms of social impact, making a dent in the universe, if you will, this one’s up there.”

With little incentive to walk away from an investment, Acumen has still written off a total $2.9 million. One casualty was the Affordable Hearing Aid Project; poor marketing and distribution doomed the $32 device. Efforts to bring US-based Medicine Shoppe into India came a cropper by dint of overly rapid expansion and what Novogratz calls “a values misalignment.”

“We know we’re going to have losses,” says C. Hunter Boll, a former managing director at Thomas H. Lee, the private equity giant, and an unpaid Acumen director, who has donated $1 million. “We’re investing in high-risk ventures in tough parts of the world.” Boll concedes the whole enterprise is “harder than I thought going in. It’s difficult to find great entrepreneurs with a social mission and a business plan that makes sense.” Success, he insists, must also be judged in terms beyond return of capital. “We’re developing talent, leadership, influencing the world.”

Indeed, last year Acumen spent $682,000 on a programme to “find, nurture, support and celebrate new leaders,” says Novogratz — one line in an expense budget of $8.3 million, which, at 58 percent of revenue, is very high by traditional nonprofit standards.

“Overhead is a tricky conversation because everyone measures [it] in different ways,” says Novogratz, who personally makes $270,000. The $1.9 million spent on consultants in 2010 for, say, learning about water systems? “I wouldn’t call the work we’re doing in knowledge and metrics overhead,” she says. That $682,000 nurturing programme? Acumen responds that two-thirds of the 44 alumni of that programme have launched or plan to launch a social enterprise within five years — a down payment on future improvements to the social order.

While Novogratz officially lives in Manhattan, she spends half of her time on the road, much of it grilling potential investments and eventual end users across the developing world. The $536,000 in travel costs aside, it seems like time wasted. Acumen still boasts $88 million in assets, but pledges and grants from donors have tailed off. As the face of Acumen, Novogratz provides the biggest added value by raising donor money, rather than looking under the hood of a Gulu Agricultural Development Co. — the kind of task Acumen’s 26 portfolio associates are perfectly qualified to do.

Novogratz thinks her travels send a message: “There’s a real moral imperative in being an organisation that takes the time to sit and listen to the customers and the people they’re serving.” More critically, she sees a direct correlation between shoring up her donor stream and the scribbles in her notebook.

That’s why I find myself in a village 10 miles outside the city of Lahore. Novogratz has come to check on another investment — and to collect the precious data she hopes to use in new fundraising. Here on 20 acres, Saiban, a non-profit developer, has built homes for an eventual 450 Pakistani families, most of whom earn $2 to $4 a day. The $4,000 units are 85 percent occupied.

Novogratz sits with a pre-selected group, red journal open and pen poised. “How can you help me describe how life has changed since you moved to Saiban?” One man speaks of greater confidence and optimism; another mentions the community spirit.

These aren’t the answers Novogratz is fishing for. She wants to hear examples of people using their homes as collateral to get college loans for their children or amassing a better dowry for their daughters so they can marry into a more prosperous family. She wraps up the meeting. “So, the next time I come, you’re going to have some good metrics for me? ’Cause this is my challenge for the world.” Someone says, “Inshallah [God willing].” Novogratz smiles, but shakes her head: “Not inshallah. We’re going to do it!”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)