Auto Parts Giant Dana Holding is Changing Gears

Here’s a surprise: After a decade of debacles, auto parts titan Dana Holding is finally turning around, thanks to a new CEO with global ambitions

Roger Wood looked at Dana Holding and saw possibilities. In the past decade the storied Maumee, Ohio, auto parts maker had survived a misguided acquisition binge, a hostile takeover attempt, an accounting scandal, a bankruptcy filing, a taxpayer bailout of two of its largest customers and the Great Recession.

It had dumped a bunch of odd- ball assets, including an olive farm in South America, a jet-leasing business and a ski resort, but with six CEOs in eight years (Wood was the potential lucky number seven), Dana remained adrift, a 108-year-old company in search of a new beginning.

“I found a lot of confusion about what this company was doing and where it could go,” says Wood, 50, in what could be the auto industry understatement of the decade. “But I saw a real jewel in these technologies we had, if we could put them together in a simple, sustainable strategy.” He joined as the CEO in April 2011, ditching a comfy slot near the top of rival BorgWarner, where he’d worked for 26 years.

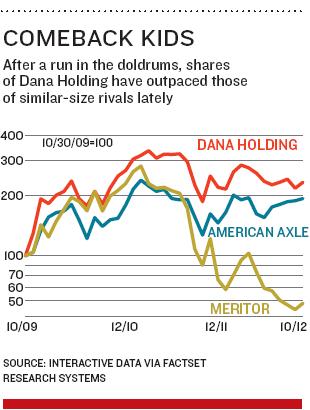

If that seemed like a fairly suicidal career move then, it doesn’t anymore. Written off for dead after going bankrupt in 2006, and then racking up another $1.1 billion in losses after emerging into the teeth of the recession in 2008, Dana is—impossibly—back. It returned to profitability (barely) in 2010 and is now on a roll, with six consecutive positive quarters. Year-to-date net income is $212 million, and third-quarter adjusted EBITDA (Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amirtization) margin improved to 11 percent, despite a 12 percent drop in sales. “The transformation of the company is very much on track,” says Barclays analyst Brian Johnson, who calls Dana “one of our top choices in a rocky market”.

Founded in 1904 after Clarence Spicer patented the encased univer- sal joint, which enabled the modern- day automobile, Wood saw similar engineering prowess buried inside the company now. Under Wood, Dana would build three things: Drivelines (which transfer power from the transmission to the axles), sealing systems (which reduce oil consumption and emissions) and thermal-management systems (which control temperatures in batteries and other components).

Growth would come from devel- oping products that make vehicles cleaner, more efficient and better-performing. It used a proprietary magnetic-pulse welding process, for example, to develop a lightweight, one-piece aluminum driveshaft that improves fuel efficiency for both light vehicle and commercial truck customers. Another Dana technology speeds the warmup phase when a vehicle is started, reducing emissions and improving fuel economy.

Wood also stepped up efforts to grow in places outside the US. Last year, for instance, Dana sharply raised its stake in a Chinese joint venture with Dongfeng Motor, China’s leading manufacturer of commercial vehicles, from 4 percent to 50 percent. Dana’s geographic footprint has changed dramatically. As recently as 2009, 51 percent of its revenues came from North America.

By 2011, that figure was down to 39 percent, with Europe accounting for 25 percent; Asia, 20 percent and South America, 16 percent. Today, Dana operates 96 major facilities in 27 countries and develops technology in 15 regional engineering centres around the world.

The strategy has worked so far. But, like many companies, Dana is running into economic headwinds. Commercial vehicle production in the US is softening, China is slowing, Brazil’s torrid growth is on hiatus and Europe remains difficult. On October 26, Dana lowered its earnings forecast for the remainder of the year, citing weaker demand.

“Volatility in our markets is a fact of life,” says Wood. He says Dana has lowered its break-even point and changed its product mix to eke out profits even in a downturn. “Economic and market conditions may change, but the value drivers of fuel efficiency, emissions and vehicle operating costs are here to stay. So we are aligning our technology portfolio with them,” he says, adding: “I didn’t make Dana a technology company. It always was. But in the last decade it got confused.”

Did it ever? The seeds of disaster were planted in the 1990s, when Dana, flush with cash that came from selling axles and other parts for pick-ups and SUVs, went on a spending spree, making at least 10 big acquisitions in the US and abroad. In 1998 alone, the deals added more than $4.5 billion to Dana’s annual sales. Employment climbed from 50,000 to 80,000 in 12 months.

By 2003, however, after a downturn in auto sales, Dana reversed course and began divesting billions of dollars in assets, including the $2 billion automotive aftermarket business it had acquired just a few years earlier.

In autumn 2003, an industry rival, Meritor, launched a hostile takeover attempt, which failed. In the midst of it, Dana’s chief executive, Joseph Magliochetti, suffered a heart attack and died. Later, the company restated 2004 and first-half 2005 results after an internal investigation discovered improper accounting.

In March 2006, Dana filed for bankruptcy protection. Its restruc- turing was aided by Centerbridge Partners, a private equity firm recruited by Dana’s unions. The two sides negotiated groundbreaking labour savings that would later serve as a model for General Motors and Chrysler, including a two-tier wage structure and the transfer of $1.5 billion in retiree health care obligations to a union-run trust.

Centerbridge was the lead investor in Dana’s financing package when it exited bankruptcy in January 2008 and remains involved today with a 9 percent stake and three seats on the board of directors. “Private equity guys get bashed,” says Wood. “But they were there when this company needed them.” Centerbridge managing partner Mark T Gallogly is understandably happy. “Dana,” he says, “is a company transformed.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)