A Beautiful Mine For Sesa Goa

Under Vedanta's fold, Sesa Goa has transformed into an aggressive, growth-hungry mining company. Its Liberian acquisition could catapult it into the top ranks globally

The Mano river runs along an iron ore-rich region in Liberia in west Africa. The region has attracted much attention from global mining companies, though most have been wary of investing in a country with a recent history of civil war.

Not Sesa Goa. The team led by Managing Director P.K. Mukherjee was keen to acquire a majority share in Western Cluster, which had access to mines along the Mano with deposits of up to a billion tonnes of iron ore. On August 5, 2011, Sesa Goa announced the acquisition.

The Liberian acquisition has now given the Indian mining sector its first global player. The African operation will be Sesa Goa’s single largest facility. This lift in status is not the only change in Sesa Goa in the last five years since Vedanta Resources acquired it from Japan’s Mitsui. From a perennial underachiever, Sesa Goa has transformed itself into an ambitious, growth-hungry miner, even as it has come under scrutiny from social activists and environmentalists.

The acquisition wasn’t an easy one for Mukherjee. He first had to convince Vedanta Chairman Anil Agarwal, who had aired his reservations when a proposal to invest in the region came on the table in early 2011.

The conflict in the neighbourhood wasn’t what was bothering him; Agarwal has an inherent liking for assets that at least have a basic skeleton in place and could be built on. From Vedanta Resources’ first major acquisition—Madras Aluminium in 1995—to the latest in Cairn Energy, Agarwal has shown an eye for, what insiders call “brownfield assets”. This preference has been reiterated by the not-so pleasant experience in the first major project that Agarwal built from scratch, the aluminium refinery in Orissa.

In Liberia, the equity buy would cost only $90 million. But Sesa Goa would need to pump in another $3 billion to explore and develop the mines. Most of the money would go in building infrastructure, including a railway line.

But for Mukherjee, the project was a must. “We had been scouting for mines in Australia, Brazil, Africa and even in India,” he says. But steep valuations meant none of the properties made the cut. “We don’t look at assets that don’t promise at least a 15 percent rate of return on the investment,” he adds. The Liberian acquisition was an opportunity to make an “early-stage” entry in a prospectively rich asset.

But there was another, unsaid reason why the 57-year-old chartered accountant was keen to invest in Liberia.

For more than a year, the stock of India’s largest private iron ore miner had been battered on Bombay Stock Exchange’s sensitive index or Sensex.

The investor community hadn’t taken it kindly that Agarwal was using $3 billion of Sesa Goa’s cash to invest in Cairn Energy, an oil company. They saw this as a move away from the company’s core interest of mining. Moreover, the mining ban in Karnataka and the breakdown of a lease agreement in Orissa had shaved almost 4 million tonnes off Sesa Goa’s annual production. The company scrip had dropped by almost half from a high of near Rs. 500 a share in April 2010. Acquisition of an iron ore asset, Mukherjee thought, could bring back some zing.

Fortunately for Mukherjee, the Liberian asset was not entirely greenfield. Ore had been previously exported from two of the mines. While Sesa would need to restart operations in these mines, it could start selling ore from them as early as 2013. “This took care of the principal shareholder’s [Agarwal’s] concern as the operations would start generating cash of its own at a pretty early stage,” says a senior official at Vedanta Resources who didn’t want to be named. Soon Agarwal gave his assent. Mukherjee would privately tell a close colleague with a sigh of relief, “I had to do a lot of convincing.”

He was soon vindicated. Two days after Sesa Goa announced the Liberian investment on August 5, Jigar Mistry of HSBC Securities and Capital Markets mentioned in his report that the deal “brings Sesa’s growth story back…which has off-late hit a roadblock.” As the Sensex dived by 500 points in the next three days, Sesa’s scrip held on, dropping just a solitary point.

Says Agarwal: “The iron ore mining in Liberia is going to be another chapter of growth… our vision for Sesa Goa is for it to grow to be among the top four iron ore companies in the world.”

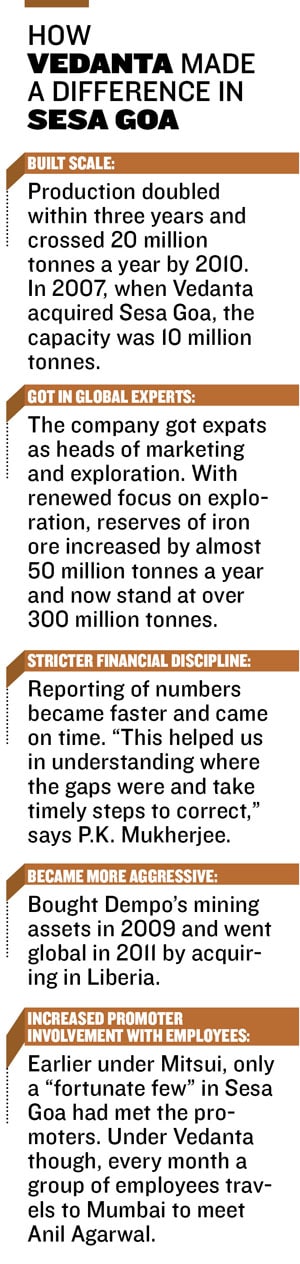

Sesa Goa’s growth story is something that Mukherjee takes immense pride in. It used to be a slumbering company that was happy producing 10 million tonnes of iron ore every year. Then in 2007, Vedanta acquired it. In 2010, its output touched 20 million tonnes; reserves of ore have more than doubled from 150 million tonnes to more than 350 million tonnes.

“We are already among the world’s top 10 iron ore exporters. In the next five years though, we will take the number four spot, both in production and exports,” says Mukherjee. That will take Sesa Goa just below the three global mining heavyweights Vale, Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton.

He credits Agarwal for the change: “After 2007, the attitude within Sesa Goa has completely changed. Now we are more growth-oriented.”

The Sesa Goa roadmap is to touch 80 million tonnes in annual iron ore production by 2016, with reserves of 650 million tonnes. Almost half of that production and reserves will come from Liberia.

By all indications, Sesa Goa is expected to increase its global footprint beyond west Africa. “At any given point of time we are looking at six or seven properties. Sesa Goa has never shied from an acquisition for want of money…it should just fit our bill,” says a member of the company’s business development team.

But Mukherjee’s rosy long-term picture runs the risk of being hijacked by the dark clouds hovering over the mining industry in Goa. In the last four months of 2011, the company scrip fell by almost 40 percent. While the overall Sensex too slid, the main reason for the fall is the ongoing probe by Justice M.B. Shah Commission into illegal mining in Goa. The report was initially expected to be submitted in December, but it has now been delayed into the New Year. Ramesh Gawas, an anti-mining activist in the state, says, “It is a clear indication the powerful mining lobby is working to delay the submission of the report. We expect Justice Shah to recommend a complete ban on mining in the state.”

Even though the final word is yet to come, its repercussions are already evident on Sesa Goa. Says S. Ranganathan, head of research at LKP Securities, “Goa approvals [for Sesa Goa to expand capacity from 22 million tonnes to 36 million tonnes] are on hold due to the mining policy and this is casting a shadow on the volume outlook for the company.” The dismal immediate future sums up what Mukherjee himself says has been “an unremarkable year”, especially compared to the first three years under Vedanta’s fold.

Agarwal was a late entrant in the bidding race after Sesa Goa’s then parent, Japan’s Mitsui, had put the company on the block in April 2007. While others in the fray included Aditya Birla Group, Essar Steel and JSW Steel, the favourite was Lakshmi Mittal’s ArcelorMittal. By the end of the race though, even a seasoned negotiator like Mittal found it tough to match the $981 million bid put forward by his fellow Londoner Agarwal. The Street had immediately voiced its opinion: Agarwal had overpaid for a company that had revenues of just over Rs. 2,000 crore and whose reserves of 150 million tonnes would be eaten off in less than 10 years.

Though Agarwal, a master in post-acquisition integration, made sure that the senior management of the company continued, tension among the top rung at Sesa Goa was palpable. “The first two years were tense, they would question everything, including our decisions,” says a senior official on the condition of anonymity. After a Japanese promoter who was happy with a moderate rate of growth and hesitant to take on any new initiatives, Vedanta’s active participation, as the official puts it, “was a culture shock!”

While Agarwal recognised “the key parameters of increasing revenues, reserves and efficiencies” as points of focus, he also wanted to bring Sesa Goa “onto the global platform through international benchmarking in all its activities.”

As a first step of doing that, he reposed his full faith in Mukherjee.

With Mukherjee in sync with his “principal shareholder’s vision”, Sesa Goa went through a dramatic cultural change. Top on the priority list were discipline in financial reporting (“If numbers came in late, we would say, no problem, get it tomorrow,” says a top official), revenue growth and bringing in global standard of operations. International professionals were brought in to head exploration and marketing. Every employee was asked to send in ideas to improve his or her department.

Sesa Goa’s revenues and profits jumped, backed by high ore prices, from Rs. 2,200 crore and Rs. 660 crore, respectively in 2007, to touch Rs. 10,000 crore and Rs. 4,000 crore respectively in 2010. Growth through acquisitions was now an integral part of the road map. It made its first acquisition in local peer Dempo in 2009, giving another fillip to output and reserves.

Agarwal showed that he was an “active promoter”. Every month, a group of employees from the rank and file of Sesa Goa travels to Mumbai to meet the chairman. “Under the earlier management, only a few privileged senior officials had seen the promoter. But now as more and more people every month come back after meeting the chairman, there is a certain spring in their steps,” says head of corporate affairs, N. Joshi. Little wonder that when asked for ideas to improve performance, Sesa Goa employees sent in 2,500 suggestions!

Sesa Goa’s good run since 2007 though went on pause when a spate of setbacks began with the ban on mining in Karnataka in late 2010. Like Agarwal’s many other companies under the Vedanta fold, the dreaded E word—environment—is now dogging Sesa Goa too.

While Mukherjee believes that the Shah Commission report will lead to a “much-needed cleansing,” he also accepts that even a partial ban on mining in the state will harm the company.

That might not be all. Apart from illegal mining, activists like Gawas have urged the Commission to look at other irregularities, including environmental violations, committed by miners. “None of the mining companies in Goa, including Sesa Goa, can claim to have completely followed the book in terms of environmental laws,” says Gawas. Mukherjee admits “there could have been inadvertent errors” but clarifies “these shouldn’t be equated with ‘intentional disregard for law’.”

The foggy road ahead continues to weigh on Sesa Goa’s scrip, which hovers around Rs. 150 a share. This might overshadow another landmark Sesa Goa is about to reach. By early next year, the company will become the country’s largest integrated producer of pig iron, a steel intermediate. The experience in value addition will help the company in its ambitions in steel making. “In Karnataka [through yet another acquisition] we have enough land to build a 3 million per annum steel plant. We also have a similar proposal in Jharkhand,” says Mukherjee.

Agarwal also has a lofty vision for the company. “Sesa Goa has already acquired a global footprint with the acquisition in Liberia and will be looking at opportunities in other parts of the globe,” he says.

But that’s still some time away. First Mukherjee will have to weather the impending storm in Goa.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)