Banking sector: A private affair

Private banks are dominating the sector as public banks lose ground

Image: Rupak De Chowdhuri / Reuters

Image: Rupak De Chowdhuri / Reuters

The Indian government has privatised very few public sector enterprises over the years. However, some of the sectors it has opened up for private participation have been taken over by private companies. Airlines and telecom are the two best examples. Air India now has around 12.3 percent of the domestic market share. And the best days of BSNL and MTNL, both government-owned telecom companies, are behind them.

The larger point is that even though the government did not privatise the public sector companies in these sectors, the sectors themselves have more or less been privatised.

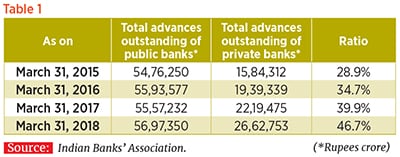

Something similar is now happening in banking. While the government refuses to privatise any of the 21 public sector banks (PSBs), the sector is gradually being taken over by private banks. Table 1 shows the total outstanding loans of PSBs and private banks, and tells us the following:

- Outstanding PSB loans have barely grown in the last four years, indicating that they are not resorting to too much new lending.

- In contrast, outstanding loans of private banks have grown at a good pace in the last four years.

- The ratio of outstanding loans of private banks to that of PSBs was 28.9 percent in 2014-2015, and 46.7 percent by 2017-2018. This means private banks are cornering a bigger chunk of the overall market, every year. The table, however, does not bring out the gravity of change that is taking place.

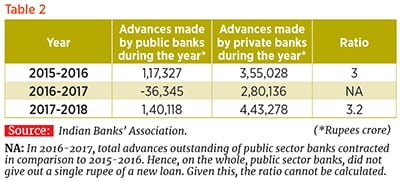

Table 2 lists the total loans given by banks during the course of a year, over the last three financial years. It shows that in each of the years, private banks have lent much more money—3.2 times more in 2017-18—than their public sector counterparts. The Reserve Bank of India has placed 11 of the 21 PSBs under the preventive corrective action framework, thus affecting their lending operations. Besides, private banks, in particular the nine new generation ones, have seen the weak state of PSBs and taken advantage of it. In 2017-2018, PSBs lent ₹1,40,118 crore. In comparison, new generation private banks lent ₹3,75,445 crore, more than double the amount.

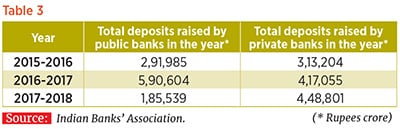

What is happening with loans is also happening with deposits, because banks cannot lend without raising deposits. Table 3 lists the total deposits raised by public and private banks in the last three fiscals. In two of the last three fiscals, private banks raised more fixed deposits than PSBs; 2016-2017 was an anomaly, as demonetisation saw much more money come into PSBs than usual. Higher deposits at private banks also show that depositors have started to recognise that PSBs are precariously placed.

As of March 31, 2018, bad loans of PSBs amounted to ₹8,95,601 crore, or 86.5 percent of the total bad loans of banks; 15.6 percent of PSBs loans have been defaulted upon.

Who loses out in all this? The government, which means you and me. An estimate by Care Ratings suggests that between April 2013 and March 2018, the government invested ₹1,70,659 crore in PSBs to keep them going, and has budgeted ₹65,000 crore for this fiscal.

As private banks gain market share, the stock prices of PSBs will be hit in the long-term (not that they haven’t been already), causing further losses to the government.

The writer is the author of the Easy Money trilogy

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)