The WeChat economy, from messaging to payments and more

Since its release in 2011, WeChat has expanded from being a mere messaging app to an all-purpose digital tool capable of everything from social sharing to investment, attracting hundreds of millions of users in the process. But parent company Tencent won't stop there

Since its release in 2011, WeChat has expanded from being a mere messaging app to an all-purpose digital tool capable of everything from social sharing to investment

Since its release in 2011, WeChat has expanded from being a mere messaging app to an all-purpose digital tool capable of everything from social sharing to investment

Image: Shutterstock

For Zhu Yile, WeChat is more than a handy accessory. The app has become a way of life. A Shanghai-based media sales manager and digital native, Zhu uses WeChat to chat with friends, share photos and videos, read news, pay bills, play games, shop and communicate with clients, colleagues and friends. Whether at home, work or on the move, she always has WeChat open on her smartphone.

WeChat, owned by one of China’s largest internet companies, Tencent, has also dramatically reduced her use of voice calls and e-mail. “The group discussion function is especially useful when we want to have a quick chat with a client that doesn’t require a face-to-face meeting,” she says. “It’s faster and more efficient than a conference call or sending a lot of e-mails back and forth.”

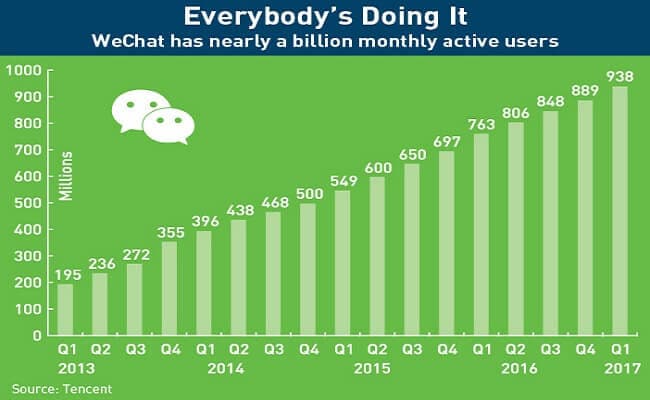

Zhu started using WeChat in early 2012, about a year after its official launch. At that time, it had just over 350 million users. Today, it is ubiquitous in China with nearly a billion monthly active users as of Q1 2017, according to Tencent. The company also claims that 50% of users spend at least 90 minutes per day using the app. It seems that Zhu Yile is not alone in her reliance on WeChat.

WeChat arrived in the right place at the right time—the dawn of China’s mobile internet era. Its frenetic growth has moved in tandem with the country’s burgeoning smartphone market, which in 2013 became the world’s largest. Backed by cash-rich Tencent, WeChat did not have pressure to generate revenues immediately. Instead, it was able to focus on building its loyal user base.

That strategy has borne fruit. WeChat is now able to monetize its legions of users by selling them games, attracting advertisers, and integrating online payment functions that encourage shopping through the app. In the third quarter of 2013, when Tencent was first trying to figure out how to monetize WeChat, company profits were RMB 4.3 billion ($630 million). By the first quarter of 2017, Tencent’s profits more than tripled to RMB 14.3 billion ($2.1 billion), beating expectations and sending the company’s share price to record highs.

With its digital payments feature, WeChat now has its eye set on becoming number one in China’s lucrative payments market, long dominated by archrival Alibaba. The stakes are enormous: according to iResearch, a consulting firm, the value of third-party mobile payments in China more than tripled to RMB 38 trillion ($5.5 trillion) in 2016. By 2019, they are expected to be over RMB 81.6 trillion ($12 trillion).

WeChat Pays

WeChat strives not only to be popular, but also indispensable. It seeks to deliver a mobile lifestyle tailored for Chinese smartphone users, serving as a platform for communication, content, gaming, shopping and even banking. The rest of the world has nothing like it.

“Outside of mainland China you need different apps to handle all the functions WeChat offers,” says Jamie Lin, co-founder of the Taipei-based accelerator AppWorks and an expert on the mobile internet. He notes that Taiwanese share photos on Facebook and Instagram, chat on Facebook Messenger or Naver’s Line (a Japanese app similar to WhatsApp), and use Apple Pay or a number of local providers for mobile payments. But in mainland China, “mobile internet users can do almost anything possible without ever leaving WeChat.”

Integral to WeChat’s rise as a dominant mobile ecosystem have been its payment functions. The WeChat Wallet, which includes WeChat Pay, comprises a selection of service providers that users can transact with after entering payment credentials. The first step is to link a bank card to one’s user account in the Wallet menu. A user can then instantly complete a transaction throughout the WeChat ecosystem: on WeChat Wallet services, official accounts with products or services for sale, and affiliated promotions. Users can also use the Wallet to send money, and even to split a bill at a restaurant—all cash-free.

What really popularized the payment function was Tencent’s clever co-opting of “red envelopes,” the Chinese New Year tradition of giving red envelopes filled with cash. In a January report, the US business magazine Fast Company noted that WeChat’s payments users more than trebled in the month that followed the red envelopes’ debut during the 2014 Lunar New Year. Over that seven-day holiday, users exchanged 20 million red envelopes, which surged to 3.2 billion the next year.

“By injecting gaming mechanics into its digital version of red packets from the get-go, WeChat helped make peer-to-peer payments a new form of social communication: sending money no longer feels tacky but socially welcomed, with a message,” wrote Connie Chan, a partner at the Silicon Valley-based venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, in a July 2016 post. “These gaming mechanics also led to much higher usage of group chats.”

Online merchants have also been integral to WeChat’s ascendance. Many WeChat official accounts (a rough equivalent of Facebook corporate pages) started linking their “blogs” with WeChat stores in order to generate sales from e-commerce, according to WalktheChat, a consultancy that helps foreign firms build a presence on WeChat.

Game developers, media, content developers, governments, hospitals, and other organizations are encouraged to integrate WeChat Pay onto their service platforms. Their consumers can then make purchases with WeChat Pay, says Nephy Hu, an industry analyst with the Taipei-based Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute (MIC).

Businesses encourage the purchase of their products and services through WeChat with incentives such as loyalty cards, membership schemes and discounts for paying online. The use of QR codes, an advanced bar code, makes it even handier—simply scan and send money.

Today, WeChat has over 300 million active users regularly using the payment functions (it launched in August, 2013.) “I use WeChat like a bankcard to pay for restaurant meals, taxi rides and groceries,” says Rachel Chen, a recent college graduate. “It’s very convenient for me because I don’t have any credit cards.”

Tenpay, which powers the Wallet, charges users a 0.1% transaction fee for withdrawing sums above RMB 1,000 ($147.11) from their WeChat accounts. It is easy to avoid the fee: simply leave the money in the WeChat balance or use it within the WeChat world. Observers say the fees encourage users to keep money circulating within the WeChat Wallet ecosystem and encourage spending it within the system.

Global Ambitions

With its strong presence in China, WeChat is naturally seeking to expand overseas, and some analysts are optimistic about its prospects. “The rise of technologies and connected networks in developing countries will become major growth drivers for WeChat,” says Julia Chiu, an industry analyst at MIC.

In Southeast Asia, WeChat is not the largest instant messaging app, but it has succeeded in building a strong presence in Myanmar and Malaysia, she notes. “The market conditions in Myanmar and Malaysia are favorable for WeChat as those countries have a large number of merchant stores that target Chinese customers and tourists,” Chiu says. “In Malaysia, the Chinese population accounts for 23% of the total population and they rely heavily on WeChat for family and interpersonal interactions.”

Further, WeChat has launched a service platform in Myanmar based on the Myanmar language and has successfully partnered with local players to increase its user base there, she adds.

Elsewhere, however, WeChat’s expansion has not gone so smoothly, even in markets close to mainland China geographically and culturally. In Taiwan and Hong Kong, most people using WeChat are those with friends and business partners on the Chinese mainland. And they typically use the app only to communicate with people based in the mainland, but not with each other.

“WeChat is still primarily used by the mainland Chinese population, and has not expanded well globally,” says Zhong Zhenshan, Vice President of Enterprise Research at IDC China, a research firm.

To be sure, the international version of WeChat lacks many of the seamless qualities of the Chinese one, and works more like an ordinary messaging app. But even if it did offer more features to Taiwanese users, they may not use them. “Taiwanese like different apps for different things, so the idea of a single mobile ecosystem to handle everything isn’t so attractive,” says Lin from AppWorks.

In many developing countries, WhatsApp has been more successful than WeChat, Lin says. “WhatsApp goes for market share first and functionality second. They keep the platform light to begin. It’s effective in building up a large user base quickly.”

Further, the WeChat user experience is inconsistent outside of China, Lin observes. “The Great Firewall of China is a problem,” he says. “Since the servers are all based in China, WeChat simply works better for users who are within the confines of the Chinese internet.”

In some cases, WeChat has failed to do its homework on the countries where it expands to. In May, Russia blocked access to WeChat for several days because the company failed to provide its contact details to the Russian communications watchdog. “Russian regulations say online service providers have to register, but WeChat doesn’t have the same understanding (of the rules),” a Russian official was quoted as saying in an Agence France Presse report.

Despite such setbacks, WeChat remains undaunted. In April, the company expanded to the UK and plans to set up operations in continental Europe next year, but the focus will be as much on Chinese users as Europeans.

“The main reason for WeChat to expand to Europe is to allow European brands to sell products internationally on its platforms,” says Chiu from MIC. “This not only helps European stores to increase sales in China, but also serves Chinese consumers visiting Europe.”

In an interview in May with the Financial Times, Tencent’s European Director Andrea Ghizzoni noted that close to 95% of luxury brands now have a presence on WeChat, up from 75% in 2015 and 50% in 2014. WeChat’s expansion to Europe could also provide small- and medium-sized retailers with an effective channel to enter the Chinese market by helping reduce the cumbersome process of gaining sales approval for products in China.

By doing so, more users in Europe can access retailers’ store and product information more directly, “thereby enhancing WeChat’s importance worldwide,” Chiu says. IDC’s Zhong agrees: “WeChat’s massive user base… is full of potential for any company operating in China,” he says.

In May, Chinese business magazine Caixin reported that Tencent is aggressively trying to build up its network of merchants that accept WeChat pay in the US, but again, the reason is largely domestically focused. Chinese tourists spent $261 billion on outbound travel in 2016, with the United States a top destination. Tencent wants to make some of that spending abroad more convenient, and of course capture some of the money at the same time.

Back on its home turf, WeChat has a different set of priorities. With a strong foothold in so many aspects of Chinese users’ lives, the next step is to become even more indispensable. To what degree is that possible?

In the mobile payments segment, Tenpay, Tencent’s behind-the-scenes service powering WeChat Wallet, has grown exponentially over the past few years, leading some observers to predict it will eventually surpass Alibaba’s Alipay. Alipay was launched in 2004 to support online payments for Alibaba’s e-commerce platforms, and in 2014 became the world’s largest online and mobile payments platform.

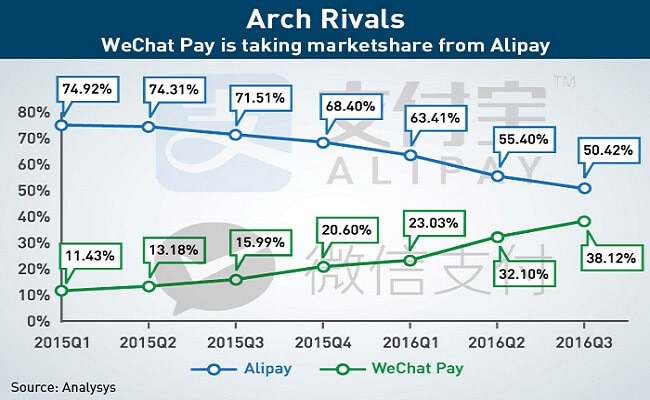

Today, Alipay remains the market leader in China with a 54% market share in the quarter ending December 2016, but that figure fell sharply from 71% in the third quarter of 2015, according to Chinese research firm Analysys. Tenpay’s share, on the other hand, reached more than 35% in the fourth quarter of 2016. Its functionality is on par with Alipay, but its edge comes from how it fits into the whole WeChat platform.

“WeChat’s threat to Alipay lies in its integration of payments with social communities and instant messaging services,” Hu says. As WeChat users spend an increasing amount of time on the app, with Alibaba offering nothing comparable to lure them away, “WeChat’s threat to Alibaba is increasingly acute.”

However, to win really big, WeChat would need to overcome the enduring popularity of Alibaba’s Taobao platform, the top online marketplace in China. Users cannot pay for transactions on Taobao with Tenpay.

Rachel Chen, who regularly shops on Taobao, says she’s happy to use WeChat and Taobao for different things. “Of course, WeChat doesn’t want users to leave their ecosystem, but they can’t force me to stay,” she says. “When I need to buy something online, the first app I think of is Taobao.” With Taobao’s huge selection of goods, she says, “It’s more convenient for buying cosmetics, clothing and electronics.”

But while the future of that all-important battle is uncertain, WeChat is simultaneously addressing other opportunities to boost engagement. One such effort is an attempt to tap China’s growing enterprise messaging market with WeChat Enterprise.

WeChat’s Enterprise accounts allow a company to set up forums, similar to the channels in Slack, a popular work collaboration app. Unlike individual WeChat accounts, the Enterprise accounts must be purchased. On the accounts, firms can conduct payroll management and enterprise-to-enterprise transactions, for which WeChat charges a 0.6% fee per transaction.

And it is not just Chinese companies adopting WeChat Enterprise. “WeChat Enterprise has become essential for foreign firms in China as it serves as an important internal communications channel between the enterprise and the employee,” says MIC’s Chiu.

Meanwhile, analysts say there is one thing that could potentially make WeChat much more dominant than it already is: mini-apps. Introduced in 2016, these mini-programs are similar to apps on Google’s Android operating system and Apple’s iOS, but use much less data. They include familiar tools like ride-hailing, buying movie tickets and applying filters to photos. “The goal is to greatly increase the things users can do inside WeChat, to the extent they never have a good reason to leave the platform,” says AppWorks’ Lin.

However, in January, WalktheChat’s Thomas Graziani questioned the viability of the mini-apps. WeChat mini-programs require developers to write in a Tencent proprietary language. “Setting a new development standard might well keep WeChat mini-programs from going mainstream,” he wrote. At the same time, the mini-apps have no official store, “leaving all the responsibility of discoverability to the publisher.”

Graziani compares the WeChat mini-apps unfavorably to Google’s Android Instant Apps. The latter, which can be accessed instantly without installation to a mobile device, boosts interconnectivity among different apps, he notes. In contrast, “WeChat is about reducing this interoperability by constraining everyone to its own ecosystem.”

Even if the mini-apps flop, it is uncertain whether WeChat’s business will be impacted, given its universality in China. Still, as a cautionary note, AppsWorks’ Lin points to the preeminence of Microsoft’s MSN Messenger during the PC era a decade ago. “MSN had hundreds of millions of users globally and earned a lot of advertising revenue,” he observes. “But it completely missed the transition to smartphones.”

Can WeChat avoid the fate of MSN? “Let’s just say WeChat will be dominant until the next paradigm shift,” he concludes.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]