Stretched to breaking point: WTO is becoming dysfunctional

Growing disputes are making the World Trade Organization increasingly dysfunctional. Will it lead to a complete overhaul?

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock The World Trade Organization has been the primary global trading system for decades, but there are increasing signs that in its current form, it no longer fits the purpose

Late last year, China’s Vice Commerce Minister Wang Shouwen, criticized the World Trade Organization (WTO), saying its very existence is threatened by serious issues. The US President Donald Trump agreed with him, albeit for different reasons. “If they don’t shape up,” he threatened, “I would withdraw from the WTO.”

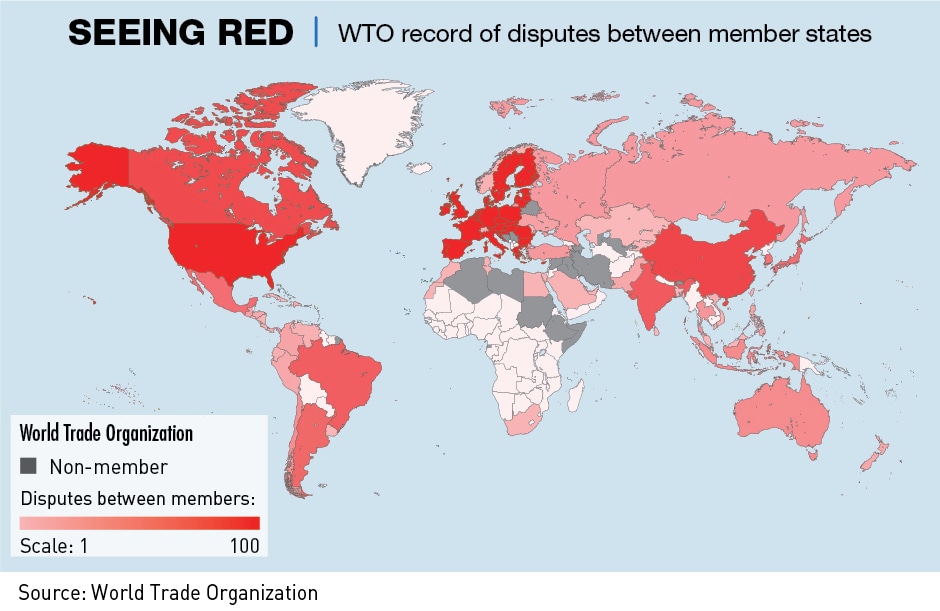

The WTO is nothing less than the world’s primary trading system, comprised of 164 member-economies scattered across five continents. It is obviously in the interests of the world that it works effectively.

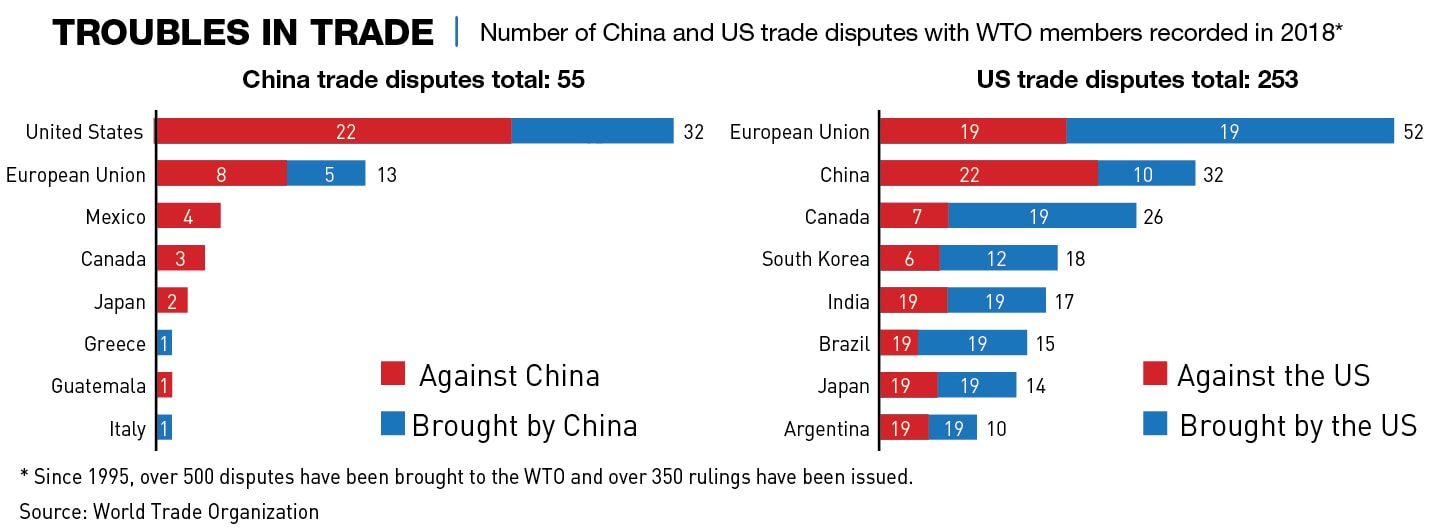

Struggling to accommodate so much diversity, the WTO has in recent years been facing an escalating standoff mainly between its three most powerful members: China, the European Union and the United States.

“Some countries are in reality just hoping to uphold their monopoly status and restrict other member states’ development,” said Wang when speaking on the WTO last year. “The WTO should prioritize key issues that threaten the institution’s existence.”

The stakes are especially high for economies such as China, Germany, Japan and South Korea that rely heavily on their exports reaching the world’s major consumer markets with low or no import tariffs. Although these countries have been doubling down on their efforts to save the WTO, it is far from certain that the system will survive.

“The WTO is in a precarious situation, and it has probably never been this destabilized and under such tensions since it was founded in 1995,” says Sebastien Jean, director of CEPII, a French center for research on the world economy.

“It has a lot to do with US-China frictions, but it goes beyond those and will not end even if the US and China would find an agreement in the near future.”

Jean explains that the main underlying problem is that today’s world is not what it was when the WTO was crafted. Global trade is much more multipolar now than it was then, and Asia has moved from the periphery of the world’s economic activity to its epicenter.

An unsatisfying status quo

The WTO replaced the old General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade system (GATT), which covered only explicit barriers to manufactured goods at the border, mainly import tariffs and quotas, with liberalization in services and agriculture being much shallower than under the WTO.

China joined the WTO in 2002, thereby leveling the world’s playing field for its export goods, catapulting the country to first place in global export rankings. The WTO is currently the only international organization dealing with the regulation of trade between participating nations by providing a framework for negotiating trade agreements and a dispute resolution process.

Meanwhile, the US trade deficit with China grew from $83 billion in 2001 (the year before China joined the WTO) to $166.3 billion in 2008 (during the Global Financial Crisis which accelerated the rise of China relative to G-7 nations) and to $566 billion in 2017 (the first year of Trump’s presidency). The US reportedly lost 3.4 million jobs to China from that time to 2017, with losses happening in every US state.

“The Trump administration’s trade experts noted that the WTO had no provisions for dealing with many of the reasons for the trade deficit, many of those relating to China’s domestic policies, such as market intervention to support state-owned enterprises and the continuation of discriminatory barriers against imports,” says John F. Copper, a professor emeritus of international studies at the US’s Rhodes College.

“Thus, President Trump concluded that the WTO was unable to solve the problem, and he had to rely on other means, namely tariffs to fix the problem.”

Besides the trade deficit, the US alleges the existence of a Chinese campaign to steal American intellectual property and force technology transfers from US companies.

To force China to address these issues to the US’s liking, the US has as of May 10 imposed 25% tariffs on $250 billion of Chinese goods. It justifies this by citing the WTO’s security exception clause, which China says violates the WTO rules as Chinese goods should not be categorized as a security threat.

China also says that the US violates the WTO’s most favored nation provision that stipulates that WTO members apply the same tariff treatment to all other WTO members. Nevertheless, arguably the most devastating shot the US fired at the WTO did not occur in the Trump presidency but under his predecessor Barack Obama in 2016.

Since that year, the US has been failing to fill vacant seats at the WTO Appellate Body, the body for settlements of disputes between members. By September 2018, the normally seven-strong Appellate Body had only three judges left, the number required to hear each appeal, and the Appellate Body would fully fail to function by December 2019, when two judges are scheduled to leave.

“The US says the WTO’s Appellate Body has developed into an international court that not only reviews the legal reasoning of the first instance of the WTO dispute settlement process but also sets new law,” says Axel Berger, a senior researcher at the German Development Institute.

“The US is also at unease with the WTO allowing its members to define themselves as developing countries, saying that China has been exploiting this loophole.”

China, for its part, argues that the WTO and all trading nations are now challenged by unilateralism and trade protectionism.

Pointing at China’s own misgivings vis-à-vis the WTO, China’s Vice Minister of Commerce, Wang Shouwen, said reform should rectify the long-term severe distortion of international agricultural trade caused by excessive agricultural subsidies in developed member countries.

China as well as India have criticized the subsidies that the EU and the US give to farmers, arguing that they lead to increased export production and artificially low prices, which in turn hurt the farming sectors in developing countries.

Wang furthermore argued that reform should relieve the severe impacts on the normal international trade order imposed by the abuse of trade remedies, especially the “surrogate country approach” in anti-dumping investigations.

The “surrogate country approach” allows WTO members to determine whether China is exporting products below market value by comparing their prices with prices and costs in a third country and levy high tariffs against China in anti-dumping investigations. China says it is unfair that the “third country” used for comparison is often a developed market economy where production costs are higher than in China.

“China’s economic miracle made good use of the WTO, and it wants the WTO to survive, given that it provides the stability and predictability China’s export sector needs,” says Jean, the director of CEPII. “On the other hand, China wants to be treated fairly, and there is that Chinese perception that China has been opening its markets much more under the WTO than India, for example.”

The cost of its unraveling

Most observers prescribe to the notion that the consequences of an unraveling of the WTO would be unilateralism, economic nationalism and trade wars that are largely unconstrained.

The world’s smaller economies have much to fear if the Trump administration achieves its goal of turning the WTO back into a GATT-like regime, where member states have a veto right should the dispute settlement committee rule against their interests.

This somewhat resembles ASEAN where disputing members can resort to any among a number of fora for settlement of disputes at any stage, so that in fact the ASEAN Appellate Body has never sorted out a dispute until the end.

“A return to GATT would mean the power of the strongman would replace the power of the law,” says Berger.

“And, as the G-20 [a group of 20 important economies] becomes the main format of moving the WTO reform debate forward, smaller countries would no longer be involved in this debate. We need to ensure effective outreach processes of the G-20 to ensure that the interests of developing countries in particular are taken on board.”

Similarly, although Trump has said he would like to see the WTO replaced with many bilateral agreements between countries, it would be an undesirable outcome for smaller countries, as they would almost certainly be on the short end of the stick should they negotiate bilaterally with an economy that is far bigger.

“A network of bilaterals would not only be unfair but also so terribly complex that it would not be an option for the world level,” says Jean.

Ming Du, a professor and WTO expert at the UK’s Surrey University School of Law, believes that the US dropping out of the WTO and even more so an end to the WTO would certainly mean serious economic worries for China. This is indicated by the effects that US tariffs are already having on Chinese goods.

China’s economy grew at its slowest recorded pace in 28 years in 2018, amid a standoff with the US as its largest trade partner.

Du explains, “of course, China cannot accept such an outcome, and it therefore strives to form alliances to gather support for the WTO in order to improve the system’s efficiency.”

No quick fix

In November, the EU together with Australia, Canada, China, Iceland, India, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore and Switzerland unveiled a proposal for concrete changes to overcome the current deadlock in the WTO Appellate Body, including new rules for outgoing judges.

Meanwhile, Trump has been calling for a “comprehensive agreement on a large range of issues” between the US and China to resolve their current trade conflict. Under a bilateral US-China free trade agreement (FTA), the two countries could create an entirely separate dispute settlement system to uphold the deal.

As WTO rules allow its members to have such FTAs that provide broad discretion to improvise on how to enforce any disputes, a US-China FTA would not necessarily mean the US drops out of WTO.

However, casting doubts on the prospects for such a comprehensive US-China agreement, Cui Tiankai, the Chinese ambassador to the US, in February said that while certain commitments such as purchases of US goods could be realized by China in a short time frame, structural reforms to China’s economic and trade policies being pushed by the US “could take years to enact,” as they would have to go through China’s legislative process.

A way out for the WTO might be that like-minded members will get together more often for specific issues.

An early example was Canada in October inviting 13 WTO members but not the US and China to a closed-door session on reforming the WTO’s dispute settlement system, improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the WTO monitoring function and modernizing trade rules.

Another example came in January when 48 WTO members, including China, the EU and the US, in January launched discussions on a digital trade accord that would reduce cross-border hurdles to e-commerce.

China, which for years has restricted use of the internet inside its borders, until the last minute resisted joining the talks. By contrast, the US has been keen on getting discussions on e-commerce going.

While some observers said the talks on a digital trade accord shows that the WTO is still alive, others see the challenges for it to survive are still daunting.

“It is much easier to destroy than re-establish the multilateral trading system that provides predictability for businesses, the governments and other stakeholders and reduces the costs of addressing trade disputes,” says Heng Wang, a WTO expert and professor at Australia’s University of New South Wales.

The problems seen in the WTO may also be reflective of an underlying breakdown of the deeper global trading systems and economic arrangements.

“But pitifully, the WTO reform is probably more about the gap between major economies on the major legal issues than technical aspects,” says Wang, “it is not easy to find promising proposals for reform or modernization of the WTO on the table.”

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]