Direct to My Pocket: The DTH Tug of War

DTH operators want to pay channel owners less, and their increasing clout makes them difficult to ignore

Every fifth satellite pay TV subscriber in the world is an Indian, no mean feat considering that DTH operators have been in India for just five years. Unfortunately, all six DTH operators together rake in just 1 percent of the global subscription revenue, according to research firm Screen Digest. Also, every single one has yet to post profits.

“Most DTH operators are still seeding the market and, in the process, still bleeding,” says Rajesh Jain, head of KPMG, India’s media and entertainment practice. The DTH operators now want channel owners, commonly called broadcasters, to share their burden.

The Conundrum

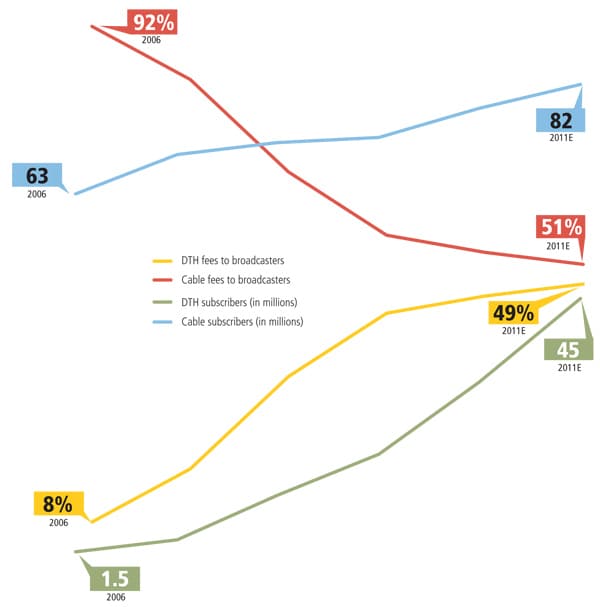

DTH operators pass on 40 to 60 percent of each subscriber’s fee to broadcasters as license fees. For DTH operators to make profits, this needs to come down to 30 to 40 percent, says Jain. That can only happen if either the subscribers pay more or broadcasters charge less.

Increasing subscription fees is not an option, thanks to competition from cable operators. “The cable industry suppresses fees in urban markets. For instance, in Agra, cable TV subscribers pay Rs. 80, and we have to compete against that,” says Ajai Puri, CEO, Airtel DTH.

That’s a Quixotic battle, say broadcasters. “Have we asked them to do that? If their business plan is to make money via market capitalisation instead of fees, then someone has to bear the cut,” says Gurjeev Singh, CEO, STARDEN, a distributor of 30-odd channels including to DTH and cable operators. (Network18, Forbes India’s parent company, owns a stake in STARDEN.)

The only other option for DTH operators is to somehow trim the share of revenue they pay broadcasters.

And most of them are doing so by scooping up as many subscribers as they can because the more subscribers they have, the less they owe to the broadcasters. This equation works because the predominant contracts between DTH operators and broadcasters over the last couple of years have been ‘fixed fee’ deals, usually struck for a three-year period. This means DTH operators pay a fixed amount to broadcasters, regardless of the number of subscribers added every month.

Tata Sky was the first DTH operator to strike fixed fee deals in 2006. Today, nearly 70 percent of all content deals have fixed fees, says Singh.

Dish TV, India’s oldest and largest DTH operator, reduced its content costs from 61 percent two years ago to 39 percent today. Salil Kapoor, its COO, says fixed fee deals helped them turn their first ever earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) profit last year.

Changing Power Equations

2011 is the year when many of the major fixed fee deals are coming up for renegotiation. A few years ago, most DTH players were on a weak footing due to small subscriber bases. But things are different now.

Infographic: Hemal Sheth

“Today, all of us put together have around 30 million subscribers, with another 14 million likely to be added next year,” says Kapoor. Airtel DTH, one of the youngest entrants in the market, claims to have added 4.9 million subscribers in the last two years. Such a significant viewer base cannot be ignored by broadcasters anymore.

DTH operators are also getting restive. “Companies that were looking forward to breaking even with between four and five million subscribers are now hoping to do so with seven to eight million subscribers,” says Jain.

Therefore, last year, after much lobbying, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) reduced the upper limit of what DTH operators should pay broadcasters from 50 percent of cable TV rates (what cable TV operators pay broadcasters) to 35 percent. This was based on the logic that cable operators report fewer subscribers (between 30 and 80 percent less) to broadcasters and hence DTH operators should be charged only a fraction of cable subscription fees.

“We wanted it to be even lower, at 10-15 percent. The actual DTH rates negotiated are usually 10-18 percent of cable rates, so why not just make that the de-facto pricing?” says Puri.

But broadcasters were worried that this would prompt cable operators to seek even lower rates. So they got the Telecom Disputes Settlement & Apellate Tribunal (TDSAT) to stay TRAI’s order. DTH operators took the matter to the Supreme Court, which last month stayed the TDSAT’s order

staying TRAI’s order!

The final weapon DTH operators are using against broadcasters is the option wherein subscribers can pick a single channel.

Last November, TRAI had said that all DTH operators would need to offer a la carte pricing of all channels to subscribers. In reality, a la carte pricing doesn’t make sense in India, where a few hundred channels are sold on an average of Rs. 150 a month.

Instead, the TRAI order presents DTH operators with another bargaining tool against broadcasters: Any channel that is removed from one of the cross-subsidised bundles and is made standalone will immediately see a drop in viewers. “For the sake of slightly higher subscription fees, no [broadcaster] would want to risk losing eyeballs and therefore advertising rates,” says Singh.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)