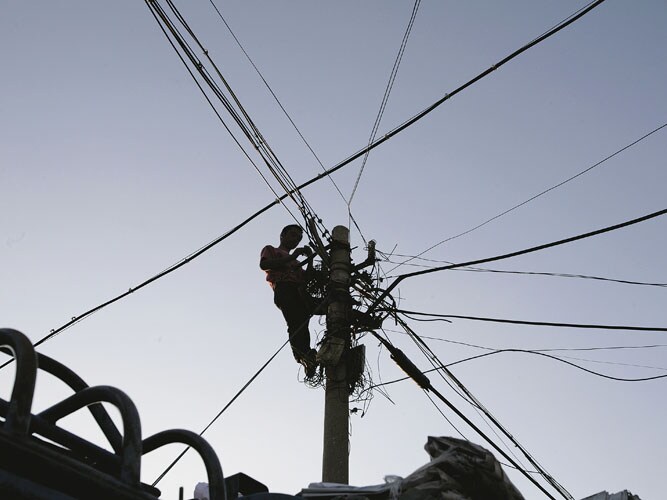

Power to the Captives

Companies that generate power for their own needs can now sell excess power

Six months ago, in an attempt to augment power generation, the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) amended its rules (Section 9) allowing any captive power plant (using 25 percent of its own power) to sell electricity through an open access system, without requiring a separate licence. Earlier, a captive power generation unit was defined as one which consumed 75 percent of the power it produced and it could sell any residual of the power it generated (subject to the ceiling of 25 percent) to the grid only after obtaining a special clearance from the government.

This regulatory change now makes captive power a very lucrative business opportunity. This move is a salve for India’s power pains because in June 2008 rules were also relaxed to allow trading of power through the Indian Energy Exchange (IEX). Given the huge shortage of power, electricity trading will allow extra power to be easily shipped to customers who are short.

In one swift move the government has made almost every process industry — steel, chemicals, cement and fertilizers — a source of power generation. These industries needed uninterrupted power. Hence, over the years they have built limited captive power capacities, which they can now expand. Some like Jindal Steel & Power are already making more money from selling power than they do selling their core product.

The lower cost structures of captive power producers (as much as half the cost of grid power) give them an edge in the marketplace. Most processes in industries like steel or cement, produce heat. This waste heat is captured and re-used to rotate a turbine that generates electricity. Aluminium and composite steel units, for instance, use a lot of coal for melting metal in their furnaces. The waste gases and heat in the kiln is converted into power. This is one of the key reasons why the cost of generating electricity for chemical and metal plants is often significantly lower than the cost at which power is purchased from the grid. In fact, in some cases like the sponge iron industry, the plant is viable only if there is captive generation of power.

What can be observed is that except for a few government-owned companies like Gujarat Narmada Valley Fertilizers Company Ltd, most players have begun using more power that is generated captively than purchased from the grid. M.S. Unnikrishnan, managing director of Thermax Ltd, a company that is setting up such plants for a variety of customers, predicts a change in power use over the years. Grid-power can be used for distributed power supply over a vast range of customers, while captive power can be used to supply concentrated clusters of consumers. “Captive power is still a very small percentage of the total power production in the country, but it needs to be encouraged,” says Unnikrishnan.

Captive projects were earlier disadvantaged over large independent power projects because the latter signed power purchase agreements with their customers, usually state electricity boards (SEBs). They were not given coal (or other fuel) linkages in the form of captive mines, nor did they enjoy guaranteed offtake for any extra power produced. But recent policy changes allow captive power projects to be allotted fuel linkages. This ensures local raw material supply. And they are now allowed to sell power through energy exchanges to both, companies and SEBs

Power industry analysts point out that producers of captive power already have the skills to manage power projects and fuel sourcing. Not surprising then that a cement producer like the Kolkota-based Shree Cements, should add to its captive unit of 120 MW — it recently announced plans to set up a merchant power unit of 300 MW to add to it. Scaling up power production is much easier than setting up a greenfield power producing facility.

The fact that the prices quoted on the IEX are higher than the price at which this power is generated, only underlines the fact that there is a lot of money to be made through this route. Return on investment will however depend on the source of fuel and the distance from the grid. In the past, revenues from power-sales have contributed substantially to the bottom lines of captive power producers like Bajaj Hindustan.

To make sale of power through the energy exchange risk free, the CERC has also amended its rules, requiring purchasers to pay up the price of the power they wish to purchase at least 25 hours before it is transmitted to the grid. This adds to the financial security of power producers as they will not be saddled with bad debts resulting from purchasers’ failure to pay up.

Clearly, very interesting days lie ahead for captive power producers.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)