Restarting Trouble in the Indian Auto Industry

India’s automobile industry has raced from a crippling slowdown to scorching growth in less than two years. But a severe shortage of parts is applying the brake in this otherwise rosy journey

The assembly lines at Mahindra & Mahindra’s car factory at Nashik, Maharashtra, are chugging nonstop again. The bitter memory of the 2008 slowdown in sales — when the plant shut down for a few days and the fear of retrenchment loomed large — seems ironic now. Every worker and every bit of machinery has been mobilised to meet the ensuing surge in demand that has seen M&M’s overall monthly sales zoom 70 percent in the last two years. While car buyers are clamouring for the Scorpio and Xylo models, the plant is also getting ready for three of the company’s new launches. Two of them will be variants of existing models and that last one, an all-new Scorpio set for a March 2011 release. By all means, it must be what they call an exciting time at M&M.

Except that it isn’t. The Nashik plant is just not getting enough components to make cars both for the existing market and to build an inventory of the new launches. Over the past eight months, M&M has seen its growth plans scuttled by an acute shortage of parts. The foreman is often forced to make less-than-optimal choices. “Every second day, there are huge discussions going on whether we should use the parts to make vehicles which we are selling or sacrifice sales to make the vehicles we have to launch,” says a senior company official. Simply put, it is a choice between making customers wait longer for their cars and going into the launches without adequate stock. “It is a huge dilemma.”

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

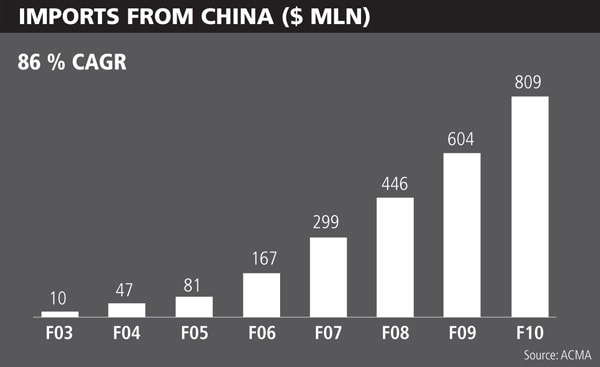

The panic button has been pressed. “We are trying out everything from sourcing parts from China [to] talking to our suppliers to put capacity expansion on fast track,” the official says.

But the battle is not being fought at M&M alone. Across the industry, from local leader Maruti Suzuki to multinationals like Ford, Volkswagen and Hyundai, the pinch of the parts shortage is being felt. No car maker is able to take advantage of the bounce-back in demand fully because their suppliers are unable to cope up with fresh orders. For customers, the delivery times have stretched interminably. For instance, it takes as much as a year to get a Toyota Fortuner, four months for a Volkswagen Polo or Vento and three months for even the well-heeled Maruti. In the bad old days, the wait times were less than a month.

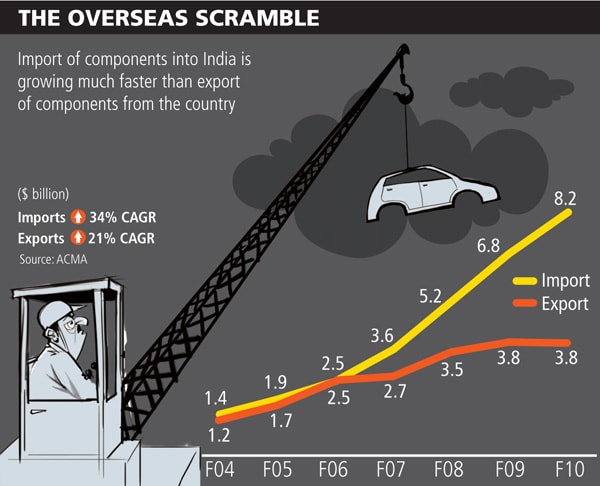

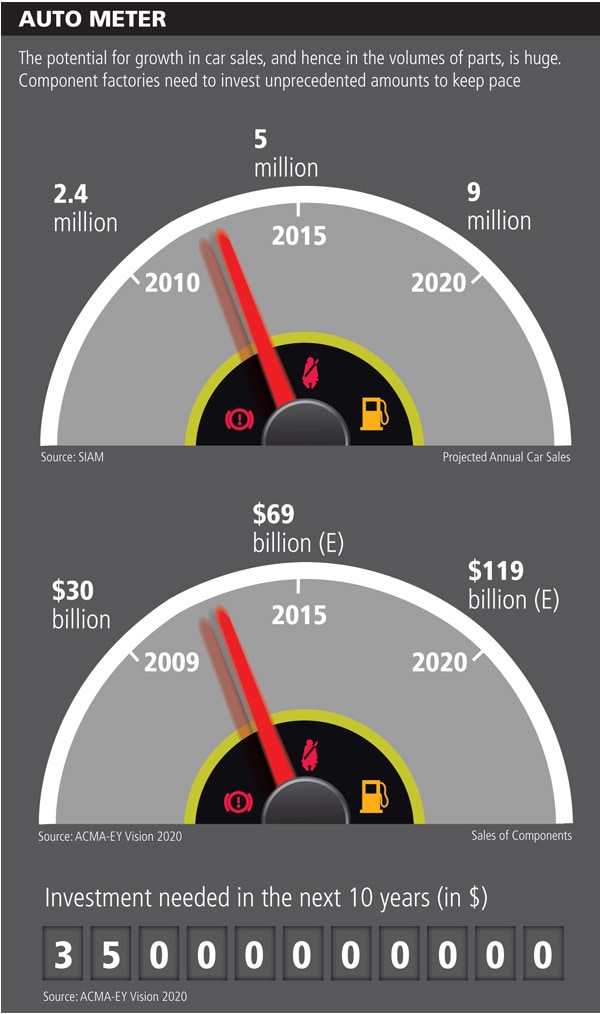

In fact, the stakes are much bigger than that. Automobile growth is a key part of India’s economic miracle. Passenger car sales are expected to more than double to at least 4 million units by 2015 and then rise to 9 million a year by 2020. The automobile sector accounts for over 4 percent of GDP and is growing almost four times as fast as the economy. But the component industry that is at the core of this opportunity is in no position to support the growth. The current logjam only shows that the problems of under-investment, lack of innovation and poor risk-taking in the component sector are translating into missed opportunities for car makers.

The Automobile Component Manufacturers Association (ACMA) estimates that an investment of $35 billion must be made over the next decade to help car makers realise their targets. But the parts industry invested a mere $1.7 billion in 2009-10, half of the required rate. Pawan Goenka, the head of M&M’s automotive division, articulated car makers’ frustration during a recent industry event when he said, “Growth will not wait for capacity. It is capacity that has to wait for growth.”

Hit and Run

Don’t ask any manufacturer of auto components about the reasons for the gaping hole in capacity, unless you are ready to listen to a lengthy sob story. Parts makers were caught off guard in the aftermath of the global meltdown in 2008, when car makers cut down production almost overnight, scaled down expansion plans and implementing a radical cost-cutting programme. All this meant lower sales for parts makers but hit them harder because they had been complacent up to that point. Car makers had initially been building inventory even in the face of falling sales and did not really prepare their suppliers for the imminent slowdown.

And that’s the way the industry has worked all the time. “Even if the demand is going to decrease, they don’t tell us,” says a supplier. Car makers fear that any advance information would lead to a cut in production at component factories and an eventual lack of supplies.

During the slowdown, when monthly sales of cars plummeted below 100,000 units, car makers cancelled a huge number of orders. Auto parts firms were forced to cut down production and reduce costs at a lightning speed to cope with this. And they were still in that gloomy mood in early 2009, when demand for cars returned as suddenly as it had vanished. “No one had expected the pick-up to be so fast and so sustained,” says Harish Lakshman, managing director, Rane TRW Steering Systems. “Many auto component companies had scaled back when the recession happened.”

Car makers typically source parts from large suppliers, who in turn, buy from smaller firms. The latter, often called the tier 2 and tier 3 companies, are proving to be the tightest bottleneck now. Even though component makers like Rane — the tier 1 guys — had invested in technology and capacity, their suppliers hadn’t.

The layoffs have come back to haunt the parts makers. They just don’t have enough people to turn the screws. A large number of talented workers have migrated from the component industry to other sectors like infrastructure, either due to job loss or better pay. Some have joined car makers. “Any trained labourer has dreams of working with a large company, eating in a better, air-conditioned canteen and earning more wages. We have been losing quite a bit of our trained labour to the OEM who has set shop in the region,” says a component supplier in Pune.

One Wheel Drive

Barring a few exceptions like Bharat Forge, the country’s auto parts companies lack global scale. Most are small single-shed operations. A large number of companies depend on just one original equipment maker (OEM) for bulk of the orders. Typically, the flagship customer accounts for 70 percent of revenues. “All your eggs are in one basket and if that customer faces a problem, you face an even bigger problem... I have seen a lot of suppliers going under just because of this over-dependence,” says a supplier who sells to Bosch.

Truth be told, component makers don’t really trust car makers when it comes to the potential for orders and growth plans. That’s because in India, only Maruti Suzuki has been able to live up to its volume commitment to suppliers. India was a painfully tiny car market until five years ago and none of the others could achieve Maruti’s scale with their launches. Be it Tata Motors or M&M or General Motors or Ford or Fiat, no OEM has been consistent with volumes. Parts makers have been left high and dry without adequate orders after adding capacity.