Mankind Pharma: Formulating Strategy To Enter The Big League

With a spot in the top three as its target, Mankind Pharma, currently eighth-ranked, is focusing on chronic therapies and exports for growth impetus

Ramesh C Juneja, founder of Mankind Pharma, works out of the first floor of an ordinary-looking building in the dusty Okhla industrial area of New Delhi. The simple exterior of his office belies the fact that this company, born in 1995, is now the eighth-largest pharmaceutical company in India (as per ORG IMS rankings). But people who have interacted with the promoters of Mankind point out that the unfussiness of the premises reflects the organisational culture. “The honesty and simplicity of the promoters percolates down the ranks. It is a quality that wins you over,” says Sanjiv D Kaul, managing director of ChrysCapital, a private equity firm which has 11 percent stake in Mankind.

Kaul fondly calls Juneja, 59, bhaisaab, or ‘big brother’ (“as does everyone else in the pharma industry”), a moniker originally held by the late Bhai Mohan Singh, the founder of Ranbaxy. That begs the question: Can Mankind live up to the name and become as formidable a player as Ranbaxy Laboratories, one of India’s largest pharmaceutical companies? (On April 7, Sun Pharmaceutical announced its decision to buy Ranbaxy Laboratories in a $3.2 billion all-share deal.)

Well, should it fall short, it won’t be for lack of ambition: Mankind’s goal, according to its website, is to become the No. 1 pharma company in India by 2015.

It is a lofty undertaking—even the promoters admit in private that this is an improbable target. But Rajeev Juneja, senior director (marketing & sales) and Ramesh’s younger brother, points out that they were within touching range: “We would have made it had Abbott not bought Piramal. There were many acquisitions in the industry. If they had not happened, we would have reached No. 1 position.” He is, perhaps, basing his statement on the past growth of Mankind.

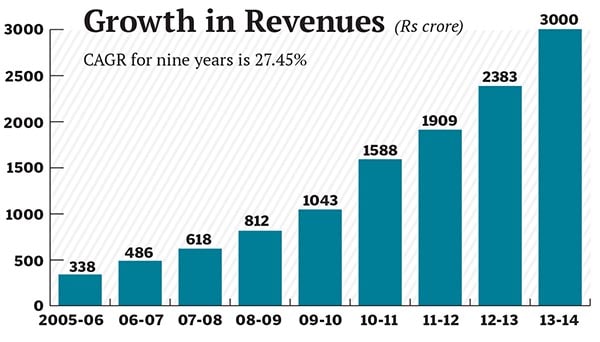

Revenues, which were at Rs 3.7 crore in 1995-96, have scaled up to Rs 3,000 crore. Leading player Ranbaxy, in comparison, had Rs 10,600 crore in sales as of December, 2013. (Ranbaxy’s financial year was from January-December.)

Kaul says Mankind’s growth is remarkable. “I don’t believe it will be No. 1 by 2015 but it will be huge if they enter the top five players segment by then,” he says, adding that while the top seven players by market share—Abbott, Cipla, Sun Pharma, Ranbaxy, Zydus Cadila, Alkem and GSK according to IMS rankings—have grown through mergers and acquisitions, “Mankind is the only company that has grown organically”.

This optimism is rooted in a two-pronged plan, going forward. One: Scaling up its chronic drugs business which currently contributes around 15 percent of revenue; the target is to increase this to 30 percent. Two: Expanding export activity, negligible at present, as the domestic market alone won’t take Mankind into the top three bracket. In the next year, it plans to target 13 countries—at present, it exports a few FMCG products and generic drugs to Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Indonesia.

Ramesh Juneja began his career in 1975 as a medical representative for Lupin Pharma. He quit in 1983 to start BestoChem Pharma with his brothers (Rajeev and Girish) and a partner Vijay Prakash; they had Rs 1 lakh as seed capital. The company sold painkillers and antibiotics sourced from contract manufacturers.

In 1995-96, when the company’s turnover was Rs 10 crore, the family exited the business over differences with the partner. Ramesh and Rajeev used the Rs 50 lakh—the amount they got as their share—to start Mankind Pharma from their hometown, Meerut, in Uttar Pradesh. They identified focus markets, drawing from insights gained by Ramesh during his stint as a medical representative. “I had travelled across UP and knew that medical representatives typically ignore doctors in small towns,” he says.

In its early years, the company sold low-priced painkillers and antibiotics sourced from other producers but branded as Mankind. Its first manufacturing plant came up only in 2001, in Paonta Sahib, Himachal Pradesh. “If you look at the Indian pharma market as a pyramid [comprising factors such as type of therapy, doctor specialisation, drug pricing], most of the companies operated in the middle of the pyramid and the leading companies focussed on the top,” says Kaul. But Mankind felt there was value at the bottom of the pyramid. “Knowingly or unknowingly, it was following the Walmart model of operating from the periphery before moving into the centre.”

Rajeev does not spout management theory; he has a simple answer to why the company chose a bottom-to-top approach: “You become creative when there is scarcity. When you have less money, no experience, no name, no background, it makes sense to tap doctors in small towns and villages. The top doctors in the metros wouldn’t have given us a second glance.”

Mankind bombarded the market with low-priced drugs (up to 50 percent cheaper), which made the competition sit up and take notice. Kaul first heard of the company during his time at Ranbaxy, as its vice president and head of corporate affairs. “In 2002, at a sales meeting, we were looking at the comparative performance of leading brands [from a particular category] in terms of market share. For the first time, I came across Mankind.” Kaul quit Ranbaxy in 2004 to join ChrysCapital and “Mankind was one of the five on my wish-list of companies that I wanted to invest in”. He started cultivating a relationship with Ramesh and, in late 2006, ChrysCapital bought an 11 percent stake in the company for an undisclosed sum. “They were, at the time, the 20th largest pharma company,” says Kaul.

Mankind had generated enough curiosity by then. “Post our investment, we realised through feedback from our friends—promoters in the pharmaceutical industry—that Mankind was being discussed in virtually every board meeting,” says Kaul.

The industry may have woken up to Mankind, but it was still an unknown commodity among some end users and medical professionals in the metros.

Ramesh says that for the first 13 years, the company worked on increasing its share in the prescription business. “We told our medical representatives to tap as many doctors as possible and generate prescriptions,” he says. The strategy worked: Mankind is the largest pharmaceutical company in India on prescriptions generated. And it currently has a sales force of 9,000.

But the brand recognition came much later, in 2007, when Mankind entered the over-the-counter (OTC) segment with the launch of Manforce (condoms), Unwanted 72 (emergency contraceptives) and Unwanted (home pregnancy kits). Mankind heavily advertised these products on TV, especially the condom brand. Till date, Mankind has spent Rs 350 crore on advertising OTC products. This created awareness for the company beyond the industry circles. “And that was the thought behind OTC,” says Rajeev. The OTC segment, which had been burning money, will make Rs 10-15 crore profit for the first time this fiscal. It contributes 8 percent to the company’s revenues.

With brand recall and market share both healthy, the Junejas have started thinking about the next leg of growth. In the last 10 years, Mankind has grown at an average of 30 percent, against an industry average of 12 percent. But to sustain this growth momentum, the company will need to sharpen its focus on specific areas: Mankind has zeroed in on the OTC segment, exports and an increased presence in the chronic therapy segment, where the company has been a late entrant.

By default, Mankind had been selling a few chronic segment products, which contributed to 0.5 percent of its revenue, but the real push came in 2002, two years after Mankind shifted its base to Delhi from Meerut. The company launched its first drug for high blood pressure, following it up with drugs for diabetes, asthma, neurology and psychiatry disorders.

A PwC report values the Indian pharmaceutical market at Rs 72,069 crore as of 2013. Chronic therapies (cardio, gastro, central nervous system and anti-diabetic) have outperformed the market for the past four years and are growing 14 percent faster than acute therapies (anti-infectives, respiratory, pain and gynecology), which are growing at 9.6 percent.

Muralidharan Nair, partner, EY India, says: “Chronic drugs generate more revenue for pharma companies because such drugs are expensive and are consumed for a longer period.” The contribution of chronic therapies to the Indian pharmaceutical market is 30 percent. Chronic therapies currently account for 15 percent of the company’s revenue. “We want to match the industry standard,” says Juneja.

Mankind is now moving towards drugs for life threatening diseases such as cancer; it will be able to enter the oncology segment in the next 12 months. “The idea is to create a presence in smaller towns and villages and then work our way up to cities,” says Rajeev. “A number of doctors in smaller towns gave us the idea to enter this segment because we have always been pioneers in cutting prices.”

Prices will, of course, be cut-throat, but Rajeev says oncology drugs will be sold at 40-60 percent cheaper than its competitors. “The approach would be oncology at Mankind prices. Otherwise we can’t break into this segment dominated by established players such as Cipla, Roche, Natco and Pfizer,” he says.

Monica Gangwani, executive director (head of healthcare), Ipsos Healthcare, India, says the fact the Indian government encourages local companies to launch generic drugs will help Mankind. “There are MNCs which launch expensive oncology drugs in India, which are patent protected. The government allows local companies to launch generic versions of such drugs to make cancer treatment affordable. So the strategy of launching low-priced oncology drugs should work,” she says.

In the oncology segment, says Rajeev, most companies tend to target the top doctors in metro cities. “There is a perception that cancer is a disease where patients go to the top doctors in the top cities. But we believe that in smaller cities as well, there are doctors who are prescribing oncology drugs. We will target these doctors,” he says.

Aashish Mehra, partner and managing director at Strategic Decisions Group, disagrees. “For critical ailments like oncology, a majority of the treatment is done out of metros and tier 1 cities. Often patients from tier 2 cities and rural areas prefer travelling to get treated; therefore the potential in tier 2 cities will be limited. Can Mankind get enough traction from smaller towns to meet their growth aspirations?”

Mankind has done well so far by exploiting an untapped market, Mehra admits. But now it will have to beat competition. “The market for chronic diseases is larger in metros and tier 1 cities because they are lifestyle diseases. This segment is already dominated by strong players with a loyal customer base. I am not convinced the capability and strength which brought Mankind here will take them there,” he says.

Mankind will also have to fight the popular perception that it is cutting back on quality to keep prices low. Ramesh refutes the allegation: “There has never been any compromise on quality…we keep our drug prices low because we don’t have highly-paid managers and our margins are lower than industry average.” Mankind’s margins are around 16 percent compared to the industry average of 18 percent.

Nair is more optimistic. “Pharma contributes significant margins to hospitals’ EBITDA. Any vendor who can offer competitive pricing is always welcome if they can maintain quality at that price,” he says.

In fact, that’s exactly the plan. Sanjay Koul, associate vice president - product management team at Mankind, says, “You have to give hospitals good margins, so that they push your product. We will take a margin hit to capture market share in the oncology segment.”

Gangwani says that if the company’s prices are low, their brands will get prescribed to the lower socio-economic category in the larger cities or to those who travel from smaller towns to seek treatment. “But then there are the regional cancer centres based in smaller cities such as Thiruvananthapuram, Patna, Allahabad, Bikaner, Gwalior, Rohtak and Shimla which would be good targets.”

The other leg of expansion will be through exports. Mankind, which started exports two years ago, will move aggressively into African, Asian, Latin American and CIS countries. ChrysCapital’s Kaul says the company can’t expect to grow by 30 percent annually with just a domestic market focus. “Increasingly growth will come from non-India markets. They are working on building export competencies,” he says.

The share of exports in Mankind’s revenues is negligible. In the last fiscal, it earned about Rs 40 crore from exports to four countries. By the end of the year, it hopes to be present in 13 countries, mostly in Africa. “We didn’t focus on exports earlier because we were working on building our export competencies. We have two units (out of 14) now dedicated for exports in Paonta Sahib,” says Rajeev.

Mankind will again target smaller towns and cities in these markets. “We will also stay away from ‘me too’ products and offer differentiated products,” says Koul. Mehra says there is a good chance of Mankind succeeding in its strategy because many of the markets could be similar to those in India. “Overseas expansion into markets similar to India, in terms of price sensitive patients, retail channel focus, large population base for chronic therapies, could be good targets for Mankind. One such is the Philippines. But the key question is: Do other Mankinds already exist in these markets, or is there a gap which Mankind could fill?”

Koul says there are companies that are targeting semi-urban markets in these countries but their products are very generic. “We have short-listed some niche products, which are yet to be launched anywhere in Africa or Asia,” he says. Mankind will look for markets where it can have a first mover advantage. “We have always believed in operating in no-competition zones. We will do the same in these countries as well,” says Rajeev. ChrysCapital’s Kaul says the company will have to pick and choose its markets: “They will have to find their niche like they did in India.”

Mankind is staying away from developed markets such as Europe, though it will export active pharma ingredients (API) to USA by this year-end. “Developed markets need a lot more research and regulatory requirements, so we decided to hone our skills in Asia and Africa before moving to developed markets,” says Mankind’s Koul.

So even though the website still proclaims a No. 1 position target by next year, Mankind has internally revised its next goalpost. “We want to make it to the top three in five years,” says Rajeev. “We have bought two small companies in the past [for around Rs 30-40 crore each] and we are open to acquisitions.” Mankind bought Magnet Labs to enter the antipsychotic segment in 2007. It also acquired Longifene, an appetite stimulant for children, in January 2010, which was earlier a brand of UCB Belgium. “The company should bring to us what we don’t have. Maybe we will buy a company in the oncology space.”

The possibilities, he underlines, are endless. “When we entered the pharmaceutical market, every company had 400 medical representatives. And now we have 2,000 medical representatives for just one division,” he says. “We changed the rules of the game. We have taught the industry that having 400 medical representatives is nothing. I am sure we will make it to the top.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)