How The Mighty Have Fallen

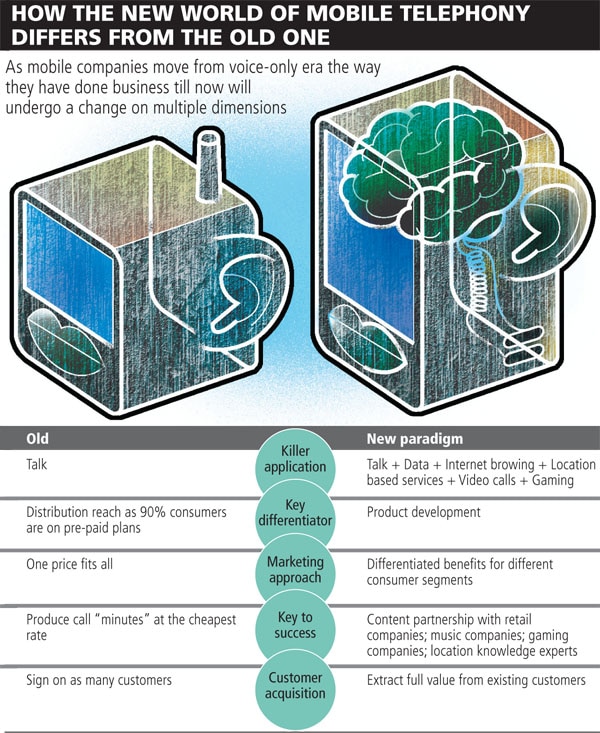

Telecom operators will have to think beyond 'minutes' and learn new tricks, or get out of the game

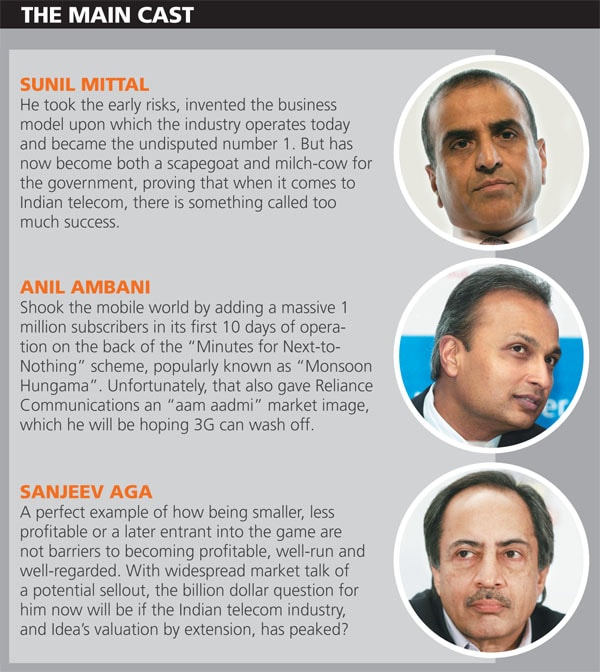

When 3G auctions were over on May 19, there was little fanfare to herald the new era in telecom, that of super-fast video downloads or electronic gaming possibilities. The mood across most operator camps — Bharti, Vodafone, Idea and even Reliance — was sombre rather than jubilant. Bharti even put out a sullen press release blaming everything from the auction format, spectrum shortage to policy uncertainty for its inability to win pan-India 3G spectrum. Vodafone’s head of strategy, Samaresh Parida, says, “Due to artificially constrained supply, the 3G auction prices were driven much higher than

expected. While the government garnered huge amounts from the auctions and the sector shares substantial revenues with it, I fear that the industry’s future could be in trouble because of high spectrum prices, large number of competitors and lack of incentives to consolidate.”

“My personal view is that the next 24-36 months will be most difficult for telecom companies but good for subscribers,” says Romal Shetty, head, telecom practice, KPMG. Super if you are planning on buying a new SIM card, not if you wanted to buy any of the telecom stocks. Most fund managers are now beating a hasty retreat from the sector. “I have zero telecom stocks in my portfolio,” says Rajiv Thakkar, CEO & director, Parag Parikh Financial Advisory Services.

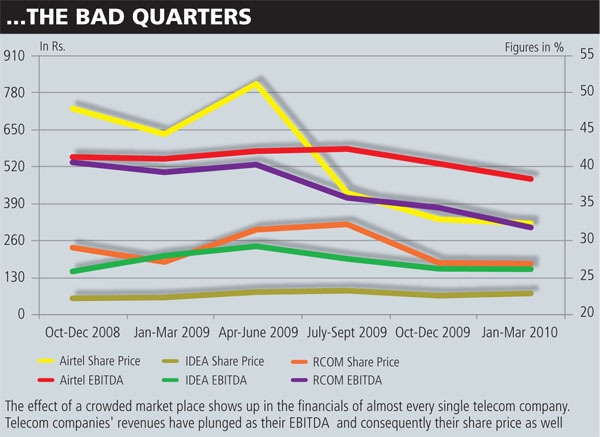

So why is a business that is so great for the consumers, a bad business now? Most telecom companies will now be adding significant amounts of debt to their balance sheet. For every rupee of equity, Bharti only had 75 paise of debt. It will now have almost Rs. 3 of debt for a rupee of equity. Yes, Bharti is different in that much of its debt is because of purchase of Zain’s Africa assets a few months ago. But look at Idea. Its debt to equity ratio will go from 0.67 to 0.96 in a year’s time. Reliance Communications’ balance sheet is already stressed and will not improve after it pays the 3G bill.

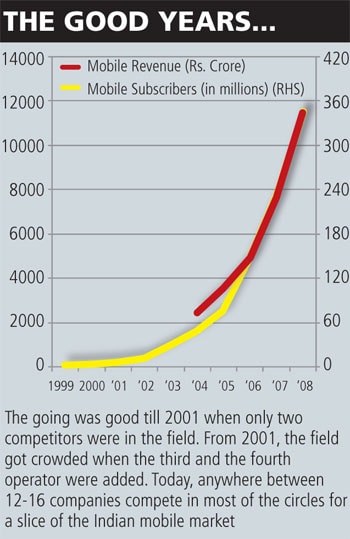

All this increase in leverage comes at a point where the money that they make has been steadily declining. Indian telecom operators say that they are in the business of manufacturing “minutes”. Well, as more and more operators have been granted licenses, the volume of “minutes” has gone up steadily.

In 2008, the industry made 250 billion minutes. Currently, it makes 600 billion. In 2008, it sold each minute for 60 paise. Today, it sells it for about 35 paise. The running cost of making minutes — without taking sunk costs into account — is now stuck at around 25 paise a minute. And this is for Bharti, which has the lowest cost. For others it is even higher. It is not surprising then that there is going to be much free cash flowing out of the balance sheets of most telecom companies. Bharti, the one exception till now, will also soon cease to remain one.

One could argue that these things are merely a blip, a part of a cycle, and that the companies will eventually find a way to make money. But that’s just optimism. The reality is that the old order of simply making minutes and selling them to ever willing customers is over. Telecom operators will have to learn new tricks and that could take some doing.

How the Body Blows Came

The reason why it will be more difficult is because almost all the parameters — customers, competitiveness, regulation and raw material prices — that define this industry have turned adverse. The humungous multitude of customers was one huge pain reliever for this industry. But they don’t make customers like they used to. You can’t blame them. After all, if the business of telecom companies is making minutes then the customers are only “minutes” shopping. “We think almost 30 percent of customers today use more than one SIM card,” says a senior executive at a top-4 telecom firm.