Hackers' Haven

India is a plum and easy target for cybercriminals and foreign governments, and unless it does something to secure itself, its strategic assets could be compromised

You work for Drewla?” The Chinese spook asked the young Tibetan girl from Dharamshala. She had been arrested on the China-Nepal border barely hours earlier.

“No.”

“LIAR! You come here to make trouble,” the angry Chinese persisted. “You are DREWLA; online network of Tibetan people who know Chinese language. You talk to innocent Chinese people to get information! SPY!”

“No. I am a student. I just wanted to see Lhasa, the land of my ancestors. I wanted to come back,” said the girl.

“READ!” said the Chinese and pushed a dossier across to her. One look and the girl knew the charade was pointless. The dossier contained transcripts of her chats with Chinese people over many years.

“We watch you all the time. We know who you are. We know what you do. Don’t ever come back to Tibet — tell your friends in Dharamshala too,” said the spook.

The Office of His Holiness The Dalai Lama, the leader of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile in India at Dharamshala, is trained to resist most temptations, but the routine email is difficult to avoid. If an email from a known fellow Tibetan with an attachment ‘Translation of Freedom Movement ID Book for Tibetans in Exile.doc’ arrives, there is no way The Dalai Lama’s staff isn’t going to open it. They clicked on the attachment, opened a Pandora’s box and brought plague upon themselves.

One of the monks working in the office realised something was amiss. He saw Microsoft Outlook Express open automatically on his machine, attach a few documents to a new email and send it to an address he didn’t recognise. Soon, the Tibetan Government-in-Exile found the Chinese in the know of The Dalai Lama’s negotiating position on various matters. Its Drewla members were being identified by the Chinese Intelligence. They realised they needed help.

When Greg Walton reached Dharamshala in June 2008, the place was ripe with humidity and tourists. For him, this was no pleasure trip though. The Dalai Lama’s Office had called him in. The Tibetan Government-in-Exile had a feeling that the Chinese were watching them.

Walton and his colleague Shishir Nagaraja, who would join him in Dharamshala in September, were both researchers and part of a project headed by Ron Deibert, an amiable Canadian with wavy hair, salt-n-pepper goatee and a Ph.D. Deibert is part professor of political science and part highly respected security researcher heading the Citizen Lab, a Toronto-based research centre.

Walton began interviewing the staff, especially the monk who had the blissful revelation of seeing his email software unfold and send emails on its own.

It didn’t take him long to understand that most computers of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile were ‘double agents’; functioning normally, but every now and then ferreting sensitive information out to their ‘command and control’ computers, most of which were in China.

It had all started the moment one of the monks clicked on a file, allowing a slimy software code to install itself on his computer and establish connections with computers in China. This malicious software — malware — would first locate important documents on the infected computer and upload them to its controllers, then try to spread itself further by sending infected emails to the contacts stored on the machine.

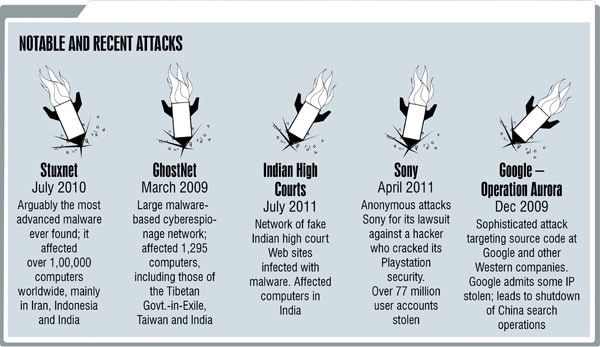

More dangerous was the fact that this malware had spread to 103 countries; 1,295 computers were infected, including those in nine Indian embassies. Deibert’s team thought their investigation, which ended in March 2009, would close the ring down. But in August 2009, they were called again to Dharamshala.

They found all the Tibetan computers infected with an even-more slimy software and were again sending information to servers in China. This time they managed to recover some of the stolen documents, 44 in all. Thirty-five were Indian. Among them, were National Security Council (NSC) assessments of India’s security situation in the North-East and intelligence about Naxalites and Maoists; reports on India’s activities in Africa, Russia and the Middle-East; the Indian Army’s artillery command and control system; and documents from private companies like DLF and the Tata Group.

Infograpics: Sameer Pawar

That’s when Deibert decided to call the Indian government.

For hackers, India today represents one of the lowest hanging fruits on the Internet, always vulnerable, always fruitful. Because within our borders they find the ideal combination of the cybercrime trifecta — plum targets, abundant vectors and lazy defences.

Tens of millions of our citizens are taking to e-commerce and Internet banking in a big way; our businesses, private and public sector, are expanding their footprint across the world even while they fight foreign competitors at home; and finally our government is attempting to play a more assertive role globally, one that is in sync with the rising importance of our economy. The payoff from attacking any of those can be immense.

Like a country filled with Trojan horses, within India also lay the tools with which to attack it. Every second computer in India is likely to have been infected with a virus in the past three months.

India is the world’s third largest source of spam three years in a row. And though it accounts for only 3 percent of Internet users in the world, India is home to 17 percent of infected ‘zombie’ computers on the Internet that can be hijacked by criminals to do their bidding.

Our security agencies and government are woefully unprepared to fight against a new class of enemies who are mostly distributed, often state-less and always resourceful.

This is why whenever a new virus or malware is discovered, India is right up there on the infections’ charts. When it comes to presence of malicious code on computers, the United States leads the world. Guess who comes second? India!

Recently, when the deadly Stuxnet virus spread across the world — almost wrecking the Iranian nuclear programme — India was up there at number three with 10 percent of all infections.

Our banks and government agencies are attacked with frightening frequency and in many cases successfully. “The number of hacking attempts or incidents has gone up sharply in the past 12 months,” says Sharad Sanghi, CEO of Netmagic, a company that hosts IT infrastructure across industry sectors. Symantec, the world’s largest security software company, says in 2010, hacker attacks increased 93 percent over 2009. How long before certain government infrastructure or a corporation’s systems fall victim to the truly ‘invisible foreign hand’?

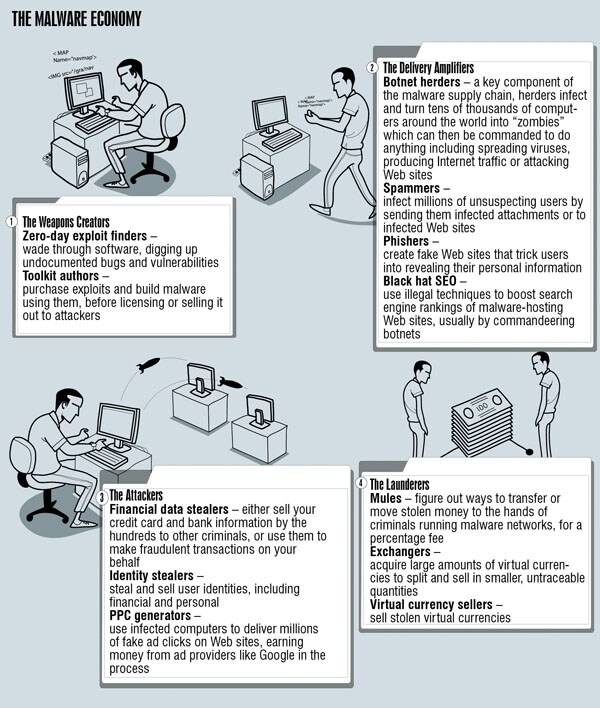

The word ‘hacker’ at once brings to mind a person who is socially dysfunctional, brilliant at software programming and with a desire to save mankind. That would be true, but now there are enough varieties to merit a zoology-like classification: White Hat, Grey Hat, Black Hat, Script Kiddies, Mules, Herders and so on.

(A White Hat gets into networks with permission, a Grey Hat works as a White Hat but may get into networks without permission for fun or profit, and a Black Hat enters networks without permission and is usually paid. Script Kiddies are those starting out in the information security world, and Mules are recruited by Herders to accept money stolen through online frauds.)

More important than the individual skills are their affiliations. At the top are the hackers with political belief. They are the Brahmins of the hacker world. The most famous of such groups is Anonymous, which, ironically, uses hacker attacks to force governments and corporations to become more transparent. It was Anonymous that attacked the Web sites of Visa and MasterCard when they stopped accepting donations meant for Wikileaks’ Julian Assange.

Barely a year ago, Anonymous got into a scrap with an Indian company called Aiplex. Specialising in anti-piracy operations, Aiplex is hired by various entertainment companies to go after sites from which you could download music or movies illegally (mostly peer-to-peer pirate sites). Though in most cases Aiplex does the boring work of serving notices that ask the owners to take down the content, when the sites don’t respond, it resorts to more questionable tactics. This includes DDoS (distributed denial of service) attacks. In DDoS, the attacker uses many systems to launch an assault on a Web site or network to choke its bandwidth so that legitimate users are unable to access them. DDoS is illegal in almost all countries, including India.

Last September, Aiplex made the mistake of launching DDoS attacks against some of the well known peer-to-peer sharing sites, including The Pirate Bay. Worse, its CEO Girish Kumar boasted about it to the press. That was the trigger for ‘Operation Payback’, a concerted hacking effort launched by Anonymous that brought down Aiplex and many Web sites related to the entertainment industry, including those of organisations representing professional artistes and musicians such as the MPAA, IFPI and the RIAA.

Anonymous’ high point came on February 4 this year when Financial Times ran an article on a US security researcher, Aaron Barr, who claimed to have uncovered the identities of its members. Barr, the CEO of security consulting firm HBGary Federal, had looked at the time when people were active on furtive Internet chat channels and matched it with information on Facebook and Twitter to guess the identities.

‘Who Needs NSA When You Have Social Media?’ was the name he proposed for a talk at a security conference to reveal his methodology.

The talk would never be given, because Anonymous got wind of Barr’s plans and unleashed their distributed hacking power at him. They got into HBGary databases and found out passwords that were being used. Because most of us end up reusing the same password across multiple sites, the cracked passwords gave hackers entry into HBGary’s email services and Barr’s Twitter and LinkedIn accounts.

Like a stack of dominoes, HBGary’s entire technology infrastructure came crashing down. The hackers posted online 4.7 GB worth of data stolen from the company, including 71,000 emails, many of them confidential. Poor Barr had no choice but to step down as CEO to save the company. “Hoist with his own petard” is how Shakespeare might have termed his plight.

“The idea of data liberation is a grey area. I suspect governments will call it cyber-terrorism when it becomes too much,” says Oxblood Ruffin, a Canadian old-school hacker.

But Anonymous stalks governments; they don’t chase money, only principles.

Corporations, especially Indian ones, need to worry about white collar criminals. These guys hire talent and technology from across the world to defraud corporations. These hackers are dangerous because for them nothing is sacrosanct.

Everyone who is connected to the Internet — small and medium businesses, big corporations, governments — is today a target for attack,” says Eugene Kaspersky, chairman and CEO of security services firm Kaspersky Lab. Kaspersky used to work for the KGB, the Soviet Union’s security agency, but now runs the $500-million Kaspersky Lab, out of Russia — home to some of the most sophisticated hackers whom criminals can hire.

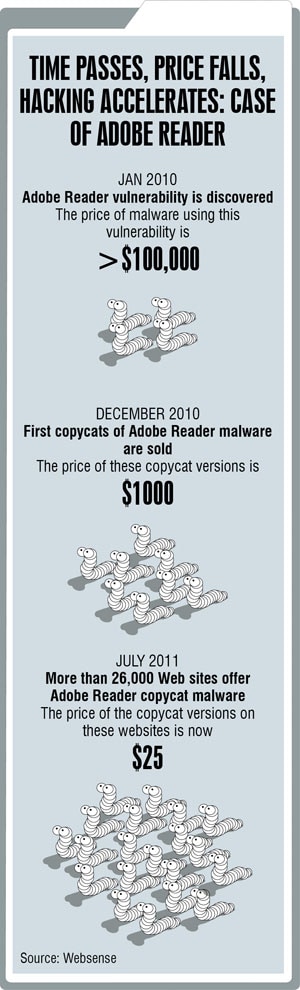

“Unfortunately, every system can be hacked. It is all about how much resources an attacker is willing to allocate for the attack, how many attackers are interested in attacking this victim. The level of risk is how interesting you are,” says Kaspersky. Today, high-grade, customised attacks become mass market products spread in pretty much the same way Prada’s high-priced summer collection becomes a flea market sensation in eight months.

Until now, except for some banks, large Indian corporations have remained ‘uninteresting’, but it’s only a matter of time. Also, Indian companies treat hacking incidents as a stigma.

“My problem is that if I try and acknowledge that a security threat was detected and we foiled the attempt the customer gets even more scared. So, I don’t ever want to talk about this in public,” says the technology chief of a large bank, who did not wish to be identified.

This only compounds matters because other smaller companies don’t have a clue of what it means to have a security breach. Take two instances.

First, a Mumbai-based mid-size infrastructure company that is mostly in the business of roads and bridges. Last year, the company found itself outgunned by competitors when it came to civil construction contracts. “Initially, the company found it odd, but thought it was a natural thing to happen in business,” says a security consultant who worked on the case and did not wish to be identified. But when it started losing contracts to an unknown firm whose holding company was based out of the Middle-East, the board got a bit concerned. They brought in the security consultant. Usually, the first set of evidence lies in computer logs but data was missing and since the company didn’t want the cops getting involved, the consultants didn’t make much headway. They did one thing though. They installed their own software that would keep track of the activities on the network.

After a couple of weeks, the software identified a file that was accessing the MD & CEO’s computer and also another computer handling all emailing tasks. The file they identified was pretty much like the malware that had managed to worm its way into The Dalai Lama’s network. The identified malware was emailing out minutes of meetings discussing various prospective contracts. Finally, it was also emailing out the ‘technical and commercial analysis of various bids’.

The episoide ended sadly with not only the key IT staff, but even the MD resigning because of the financial damage that the company suffered.

In January 2007, Network Magazine, a popular technology trade publication, did a cover story on India’s best ‘security strategists’. One of the companies profiled was Bank of India, a public sector bank with over 2,650 branches and $26 billion in assets. The bank, went the article, was “racing to be the most secure bank” in India.

Instead, it went to being the most unsecure bank in India by August 30. Sunbelt Software, a US-based security software company, discovered that day that Bank of India’s Web site was infected with 22 different types of malware controlled by a ‘fast flux network’ of servers — which makes malware networks more resistant to discovery and counter-measures — belonging to the Russian Business Network, one of the most feared cybercrime organisations. Every customer who visited the Web site risked being infected.

“Bank of India looks like a bank that never stops working regardless of the scale of the catastrophic event that it may face,” went the magazine article.

Reality was, once again, otherwise. It took the bank over 36 hours to disinfect itself, during which it bumbled about like a newborn calf. First, Chic Infotech, the vendor maintaining the bank’s Web site nonchalantly hung up on a caller who reported the incident. The caller got the same response from the Bangalore Cybercrime Cell, which refused to acknowledge or register the incident, saying only the bank could do so. Bank of India, meanwhile, issued a statement assuring customers there were ‘no major problems’.

“There are so many ways to break into a network today that you have to assume you’ve already been compromised,” says Jeffrey Carr, a cyber security analyst and CEO of Taia Global, a security consulting firm. In most cases, a malware enters an organisation through a weak link relatively lower down the hierarchy. HR departments are often the easiest way, says Vinoo Thomas, a senior product manager with McAfee, because they open tens to hundreds of PDF resumes everyday.

“In many ways admitting to a security breach is like saying you have AIDS, people are afraid to admit they have it,” says Manjula Sridhar, a security researcher and the head of sales at Arcot Systems, an online authentication services provider.

In the long run, this creates far greater problems, because criminals end up using data stolen from one breach to engineer multiple newer attacks. “If you hear about a breach and how many records the criminals got away with, those are the ones to be least concerned about, because you can change them. The ones you need to worry about are the ones you haven’t heard of yet,” says Joe Stewart, director of malware research at Dell Secureworks, a security services provider.

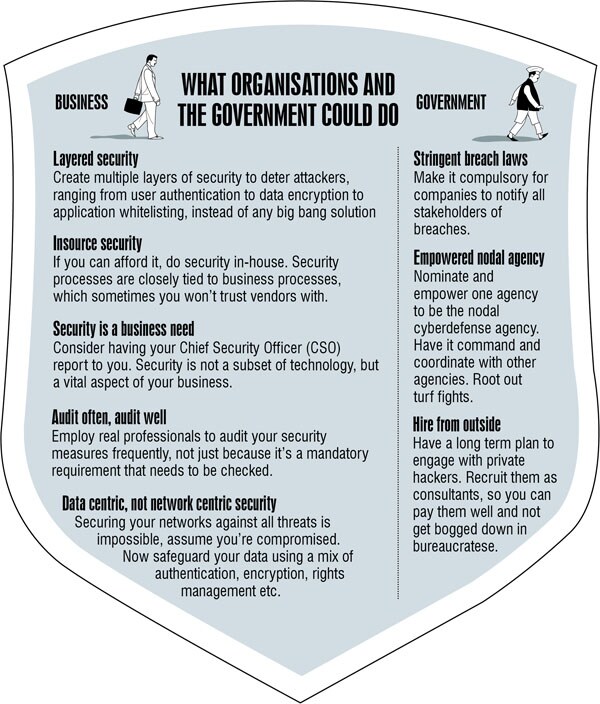

The solution is breach disclosure laws that compel companies to notify consumers or partners when their data is even suspected to be stolen, like in most states in the US. Failure to do so, often leads to a criminal investigation. The European Union too is close to bringing in a similar law.

In India, while Section 70 of the Information Technology Act makes CERT-IN, the nodal authority to receive reports of breaches, there is no compulsion on companies to report breaches.

“We definitely need a breach law. Because only when you publicise breaches will companies take security seriously,” says Shantanu Ghosh, head of Symantec India.

But don’t expect such regulation to pop up overnight. Because if it did, the government itself could win the dubious distinction of being the most-breached organisation as there have been numerous attacks on government and public sector organisations.

Also, as is the case with the government, there are multiple chefs — CERT-IN, NTRO, NIC, IB, DIA, RAW — and too few cooks!

Alphabet Soup Defense

(S//NF) SCA CTAD comment: According to Defense Intelligence Agency reporting, the Government of India (GoI) continues efforts to advance its computer security programs -- particularly in light of increased concerns over Chinese computer network exploitation efforts -- but progress is hampered by significant disagreements within its departments.

The key GoI organizations involved in developing and implementing security policies are identified as the Ministry of Telecommunications and the Research and Analysis Wing. Although the Indian Army is primarily responsible for the security of military networks, Indian officials acknowledge Army representatives have been largely left out of discussions.

Additionally, some other key groups, such as the National Technical Reconnaissance Organization (sic) and the Indian Defense Intelligence Agency, have reportedly failed to offer significant contributions.

— US Diplomatic Security Daily, Monday, June 29, 2009

Though this extract from a secret US government cable that Wikileaks revealed is over two years old, its analysis is still spot on.

India’s cyberdefense abilities are divided between an alphabet soup of agencies, many of which are manned by bureaucrats with no understanding of what they’re up against.

“CERT wants to be the lead, but nobody listens much to them because they are part of DIT (Department of Information Technology). Everybody wants to cut the NTRO (National Technical Research Organisation) down to size. Everybody wants to be the nodal point so that others work and report to them so that any credit can be theirs while the blame will be others,” says Mukesh Saini, a retired naval commander who now runs his own computer security firm called XCySS in Delhi.

According to another expert, the NTRO’s plans to raise a team of patriotic hackers too, is unlikely to deliver the expected results. Because the salaries the government is willing to pay them are not linked to the market, but to existing government salary grades.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)