DNA Newspaper Attempts Mission Impossible

Subhash Chandra of Zee and the Agarwals of Dainik Bhaskar launched DNA in 2005 to challenge The Times of India on its home turf in Mumbai. They severely underestimated their adversary

The scene could have been from the 1961 film Guns of Navarone. In it a team of Allied commandos take on the suicidal mission of destroying a massive German gun emplacement watching over a vital sea channel.

Back home, in 2005, the island was Mumbai, at Rs. 800 crore - Rs. 1,000 crore, the single largest print advertising market in India and guarded like a fiefdom for close to two decades by The Times of India.

Under the mission leaders — Sudhir Agarwal, the sharp yet unassuming brains behind the Dainik Bhaskar group and Subhash Chandra, the self-made media baron who had dared to cross swords with Rupert Murdoch — was assembled a crack team of senior journalists, marketers, salespeople and distribution experts to not just take on The Times of India, but conclusively defeat it. Their secret weapon was a new newspaper called DNA.

Once Mumbai was conquered, DNA’s gameplan was to quickly replicate its success in most big metro and city markets across the country, becoming a pan-India newspaper advertisers and readers couldn’t ignore.

But after a bruising five year battle, DNA’s original ambition lies in tatters.

With the exception of current editor R. Jagannathan almost all the senior professionals it hired to fight The Times of India have deserted it. Its readership in Mumbai is down nearly 15 percent from its 2009 peak while The Times of India’s is still 2.5 times larger. To pare down losses due to lower-than-expected revenue, the paper has been forced to progressively do away with additional supplements, reduce pages and print lesser copies of the newspaper. Its ad rates are one-third The Times of India’s on paper, but close to one-seventh in reality due to severe discounting. There’s no sign of its revenue being enough to cover its operational costs for at least another year or two, says CEO K.U. Rao, leaving unanswered the larger question of how much longer it will take for the paper’s investors to recoup the Rs. 1,100 crore they have put into the project till date.

The result: Instead of gunning for The Times of India, Rao is working hard to make DNA an economically viable business. “Our vision since day one was only to become one of the top five English publications in the country,” he says.

It’s a compromise DNA had no choice but to make.

Bruised and Battered

DNA’s current predicament followed a rather impressive start — getting from zero to 400,000 copies in Mumbai within two years. It did that by using an all-out mix of editorial star power, free-flowing cash lines from both parent investors and a product that was crisp, well-designed and intelligently written.

But though CEO Rao outwardly seems thrilled to have broken into the top six English general newspapers in India on aggregate readership, things are not so rosy when you delve deeper.

In its largest market, Mumbai, which accounts for nearly three-fourths of its readership, DNA is a distant number three after five years of operations. Hindustan Times at number four is snapping at its heels, with just 7 percent lesser readership.

In Bangalore where it launched in December 2008, it is on the verge of being dislodged by Deccan Chronicle for the number three position. In Surat it shuttered operations after launching an edition in 2007.

“It was a dream we had. We wanted to give the Times a fight and to some extent we did. I don’t know about the future though,” says Sidharth Bhatia, a veteran journalist who was the editor of DNA’s edit pages from inception till December 2009.

Financially, DNA’s future is grim. Its revenue last year, at Rs. 148 crore, was up 22 percent over the year before, but that was still Rs. 70 crore short of covering its operating costs. Cutting costs is therefore Rao’s first priority as he attempts to steer DNA to profitability.

Under Subhash Chandra’s active guidance, who started playing a more hands-on role at DNA since the last one year after taking over from the Agarwals of Dainik Bhaskar, Rao is walking the fine rope of trying to print less pages but sell more ads. DNA’s print run in Mumbai was reduced by over 100,000 copies last year to reduce its cash burn rate.

Rao says DNA will also become more hyperlocal. That means it will intensify its news coverage that is local to the reader’s location. In Mumbai it has two supplements targeted at the suburb of Thane and the city of Navi Mumbai. Doing so will hopefully allow it to attract more retail advertising. “If a Hyundai or Maruti showroom takes out ads in a newspaper, it would not take much convincing to get Hyundai or Maruti themselves to advertise too,” says the head of an independent media planning agency.

The other area where Rao has taken a knife to, is staff salaries. In 2005, DNA lured a phalanx of senior editors and journalists to join it, in many cases from The Times of India, by offering salaries that were 50-100 percent higher than their previous jobs. While this allowed it to establish the DNA brand on the back of well-recognised journalists, it also got saddled with a bloated cost structure that was very top-heavy.

As most of those journalists quit DNA during the last two years, Rao has taken a conscious decision to make the editorial team flatter and less expensive. “We started out with 357 people in 2005, and today we’re around 375. I don’t think the same seniority may be required,” he says.

Probably the most stark sign of DNA’s transformation comes from Bangalore, where just over a year after it spent nearly Rs. 100 crore to put up a state-of-the-art printing press, it is now using it to also print over 200,000 copies of Bangalore Mirror for The Times of India.

Rao’s realism is a contrast to the unbridled aggression and enthusiasm shown by DNA’s founders in 2005. In Sudhir Agarwal’s scheme of things, The Times of India should have been a sitting duck to his well-planned, military-style attack.

The Mission that Failed

The theory that DNA wanted to use against The Times of India in Mumbai was one that had been formulated and honed by Agarwal at Dainik Bhaskar. In step one the group would identify new target markets, ideally those that had a fairly large reader base with most reading the dominant but lethargic leading newspaper. Step two would see a few hundred Bhaskar staff fanning out to a majority of households in the market to conduct a market survey that would make readers come up with various qualities they felt were lacking in their current newspaper. After a few months, the team would go back to the households and show them a truncated version of a new newspaper that had been designed from their collective feedback, and oh, would they want to subscribe to it at a ridiculously low price?

By the time step four, the launch, arrived, Dainik Bhaskar would have notched up enough annual subscriptions to kick off day one with a print order that was close to the leader’s or in some cases even higher.

They called it the ‘consent booking’ model.

By launching with a circulation equal to or greater than the market leader, its new paper would immediately start getting advertisements which allowed it to break even within four years in most markets. This allowed it to copy-paste this strategy with uncanny precision in multiple markets — Rajasthan in 1996, Gujarat in 2003 and Punjab in 2006.

Most incumbents in the markets where it adopted this strategy instinctively hunkered down into a defensive mode and reacted by either cutting prices and ad rates or tweaking editorial coverage.

Unfortunately for the group, in Mumbai, The Times of India did the exact opposite.

“DNA came in with a lot of over-confidence. Heady with their launches in Gujarat and Rajasthan, they thought The Times of India would be a sitting duck. They started their outdoor campaign four months in advance, giving us adequate time to launch a new paper. I think they displayed their hand way too early, so by the time they launched we had already soaked up a lot of the reading appetite,” says Rahul Kansal, chief marketing officer, Bennett Coleman & Co. Ltd, the company that owns The Times of India.

In its first pre-emptive move The Times of India launched a new paper of its own, Mumbai Mirror — a flashy and loud tabloid — two months before DNA. More importantly, it decided to give it away free of cost to all The Times of India households. It also thoroughly revamped itself, adding pages, a revamped international news section and vastly improving its city coverage.

“DNA wanted to become the clear number 1, for which we had to offer a Times-plus-plus. But what happened in the process was that the Times improved itself considerably, so doing a Times-plus-plus became tougher,” says Pradyuman Maheshwari, a senior journalist who was with DNA between 2006 and 2007 and sat on its editorial board as well.

Then it did something nobody was expecting it to, especially after the bloody price war it had unleashed in Delhi while taking on The Hindustan Times — it increased its cover price from Rs. 3 to Rs. 4.

“In no other market has a market leader increased its price in response to competition. Our strategy was twofold: For those households that had money, give them so much to read that they would be fed up and left with no time to spare; and for those that didn’t have enough money, take it all away through higher cover prices,” says a senior executive with The Times of India who played a crucial role in formulating its counter-offensive against DNA.

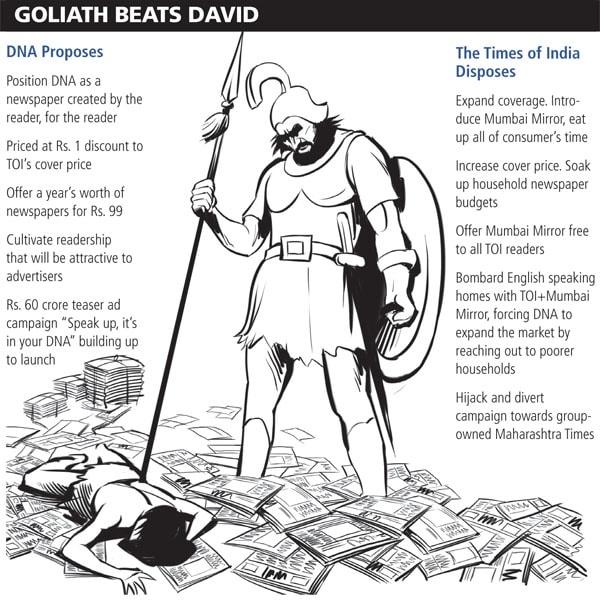

Infographic; Sameer Pawar

Times’ decision to hike its cover price stemmed from its learning from fighting The Hindustan Times in Delhi. Dropping prices means that the customer’s budget allows for two papers.

The higher cover price also allowed The Times of India to increase the distribution fee it would pay newspaper vendors — arguably the most crucial link in the newspaper distribution chain — from Rs. 1 to Rs. 1.75. This created a very stiff monetary disincentive for vendors to switch from The Times of India to other new publications like DNA which would offer them only Rs. 1.

Blocked from entering many English-reading homes because of Times’ dual-fold bundling strategy, DNA had no choice but to drop its annual subscription price to bring in the numbers. It decided to offer a year’s worth of newspapers for a mere Rs. 99.

Selling newspaper subscriptions so cheap further hurt DNA by first bringing in many readers from poorer households who weren’t the targets that advertisers would pay for, and second by creating an economic arbitrage opportunity in favour of false bookings.

In spite of a dedicated call centre that DNA put up to weed out fake orders, many were placed with the connivance of vendors and its own booking team. At the simplest level there was money to be made by selling the newspaper as scrap. At Rs. 7 per kilo people made roughly Rs. 400 by selling a year’s supply of DNA. Even worse, many vendors actually claimed back the full cover price — Rs. 750 annually — from DNA for fake orders they never even delivered because of an ill-designed vendor payment system that didn’t properly match copies delivered to monies paid out.

Retreat, Regroup…

Then What?

Frankly speaking, DNA’s options today are fairly limited. It is on the verge of becoming a number four player in its largest markets, Mumbai and Bangalore. It has given up on plans for now to launch editions in Delhi, Hyderabad, Chennai, Indore and Lucknow. If DNA ever wants to bring in an outside investor it will want Delhi as part of its footprint, but launching in Delhi will take anywhere from Rs. 400 crore - Rs. 500 crore to begin with.

Restricted to a number three or four position in a couple of markets, DNA will find it very hard to convince advertisers or media planners to consider it above or even equal to a Hindustan Times, Hindu, Deccan Chronicle or even a tabloid like The Mumbai Mirror. Media planners say the only way DNA can claw back into the race is by managing to reach around 75-80 percent of The Times of India’s readership in its key markets, something that will immediately give it currency within ad budgets. That is what The Times of India did in Delhi to The Hindustan Times.

By drastically cutting many editorial products (and staff) that made it unique, Rao may have been able to cut DNA’s losses from Rs. 158 crore for the year ended March 2009 to Rs. 70 crore this year, but in the process stripped it to a product that appeals to a very homogenous audience.

“Originally we had thought we’ll cater to lot more audiences with a lot more differentiation. But now we are falling in line with what the market requires, we are a general interest newspaper,” says Rao. Bhatia, the paper’s edit page editor till December 2009, says he’s stopped reading the paper on a daily basis now.

DNA’s failure to achieve its lofty goals seems to have also put a strain on the relations between its investors — the Agarwals and Subhash Chandra. “We were told the breakeven target was five years from the owner’s point of view. But your gestation period cannot be five years when fighting a 150-year-old giant by offering your readers significant value, value that cannot be monetised so easily,” says a senior ad sales executive who is part of DNA since its inception. “Dainik Bhaskar wanted to run it like a Hindi newspaper and was looking for a breakeven very, very soon,” he adds.

Both the Dainik Bhaskar and Zee groups did not speak to Forbes India for this story. With The Times of India continuing to use discounting strategies to dissuade large advertisers, say multiple media planners, from advertising in DNA, Rao’s ad sales teams have their backs up against a wall. “Their desperation is coming across too vividly to us sales people, which scares us even more,” says the media planner quoted earlier in the story.

“Are you sure it will work?” asks Captain Keith Mallory (Gregory Peck) in Guns of Navarone, to his explosives expert Corporal Dusty Miller, who’s come up with a plan to destroy the German guns.

“There’s no guarantee, but the theory’s perfectly feasible,” says Miller.

It’s a shame, because the theory was indeed perfectly feasible.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)