'I am relevant because I've been irrelevant': Sabyasachi Mukherjee

The couturier in a no-holds-barred interview on business, competition, why a little insecurity is nice, and choosing Instagram over fashion shows

Image: Madhu Kapparath; Location Courtesy - Grand Hyatt Mumbai.

Sabyasachi Mukherjee, 45, has carved a distinct niche for himself since debuting as a fashion designer in 1999. From tie-ups with Christian Louboutin to design shoes, to a collaboration with British luxury retailer Thomas Goode & Co to create a tableware line, he continues to push the envelope as a creative artist.

Mukherjee chose fashion as a career not because he was passionate about it, but because he didn’t want to become a doctor. A rebel since his growing up years, he tried his hand at various professions, including singing. “But I was just not ready to die mediocre,” he says. Even at the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT), Mukherjee was “one of those oversmart, bad students—the kind that teachers absolutely despise”. It was only during the last three months at NIFT, when he had to participate in competitions that he came into his own and won all awards. Later, he won the Femina Miss India’s Designer of the Year Award for which he was sent to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London on a scholarship. “It was my first flight out of the country,” he recalls.

It was only when he went to Paris for internships with Gaultier and Azzedine Alaïa for winning the Mercedes New Asia Fashion Week that he decided to set up his own label in India. After his first fashion show at the Lakme Fashion Week in Delhi in 2002, a realisation dawned upon him: “I’m going to become a big star and the next big thing in fashion. There’s going to be no stopping me.” In an interview with Forbes India, Mukherjee speaks of his two-decade journey and the changing world of fashion. Edited excerpts:

Q. How have you managed to stay relevant for 20 years?

I have never considered myself to be a fashion designer because I think I am more of a businessman. One of the reasons I have been relevant in my industry is because I’ve never been a part of it. I’ve always stayed on the fringes and observed it. Once you get into fashion, you get consumed by it and lose practicality in your quest for sartorial elegance.

When I step back, I lead a simple life. I have friends from school who are still my friends… I have almost zero interaction with the industry. For me, it was important to create a business that was financially stable. While we were going to look at active clients, we were also looking at active bottom lines. Everything was structured like a business. Every strategy was carefully thought of; you don’t grow a business without strategy. I didn’t want my business to be like an FMCG one because if you look at fashion, you call it luxury. Yet it’s the most disposable business and industry in the world. I haven’t built a business out of creating classics because for me and a lot of us, the most important thing is value. If something does not tantamount to value, I wouldn’t expect my consumer to buy it. I think my relevance comes from the fact that I surround myself with people who think fashion is irrelevant.

Q. You are one of the most plagiarised designers in the country…

I like that because I’d like to believe that you can only be plagiarised when the middle-class wants to buy you. If the super-rich wanted to buy you, you wouldn’t get plagiarised. Middle-class people are dheet (stubborn) as consumers and have a lot of sense… you cannot put cotton wool over their eyes with marketing. When I got to know they were buying plagiarised versions of my clothes, I realised that as a design philosophy there must be something that I am doing right. Because it’s difficult to get the middle-class to pay their hard-earned money to buy luxury products, or even versions of it, if they don’t connect with them.

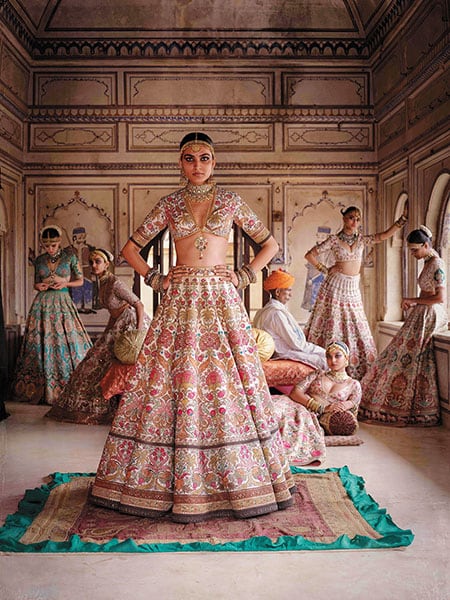

Mukherjee prefers to have his clothes hand-made, be it embroidery, hand block printing, weaving or dyeing

Mukherjee prefers to have his clothes hand-made, be it embroidery, hand block printing, weaving or dyeingImage: Courtesy Sabyasachi

Q. What is your design philosophy and how has it evolved over time?

I don’t have a design philosophy, but I have agenda or DNA. I like to make clothes which are made by hand. Whether it’s embroidery or weaving, hand block printing or dyeing, I like clothes made by hands because when you create something out of human hands, it’s never perfect in the sense that imperfections give it personality. In today’s day and age, when the world gets more and more mechanised, it’s the things that you do by hand that are becoming more and more luxurious.

Q. Your family disagreed with your decision to join NIFT. What was it about fashion that inspired you to make it a career?

I jumped into the deep end of the ocean without knowing how to swim. It wasn’t about fashion; I didn’t want to be a doctor. I dropped out of my education system because I didn’t believe in it… I thought it was too much of textbook education, barely any practical knowledge. I didn’t know anything about fashion, but I was like fine, it’s a career choice that I’ve made.

Q. What makes Sabyasachi the brand that he is today?

I have no work ego. I will do whatever it takes to survive. I worked very hard for 20 years, never lost focus, sacrificed many things—personal relationships, friendships, interpersonal relationships with my family—because of the fact that every time the company’s turnover grew, it meant more people got employed.

I was always ambitious about growth. I realised you create a business by securing your back-end first. I remember a time when my turnover was really low. I bought a huge factory on loan and my father asked why I needed to do that. I said, soon you’ll require the factory. Over the last 20 years, that factory has multiplied into 35 factories. The fact that we created so much employment in our sector is my proudest achievement in 20 years. My body of work has gone through many changes, but it still has the same DNA of the brand.

I feel awkward telling people that I’m Sabyasachi because now Sabyasachi has become a brand; it’s not me anymore. I don’t belong to myself. The name doesn’t belong to me; it belongs to the public at large. For a lot of people, the label is more important than the product. For me, fashion is a job… if you take the label off my face and put me on a train with hundred people, not a single person will ever guess that I’m a fashion designer. I don’t look like one, don’t dress like one and don’t talk like one. I’ve only been relevant because I’ve been irrelevant. If I made myself relevant, my brand wouldn’t have been relevant.

Q. What were some of the challenges in the fashion industry, especially when you started out?

At that time, the biggest challenge was infrastructure. The fashion industry has become much more organised now. But the biggest problem today is that it’s harder to create stars because there are designers coming out of everywhere. Earlier, there were just two or three names… now fashion has become the next big business in education, just like hotel management. Everybody wants to open a fashion school because everybody wants to become a designer. There has been an infusion of great designers, but also an infusion of mediocrity. It’s going to be the survival of the fittest because the consumer is becoming more aware. People are going through what we call ‘fashion fatigue’. So only those who will be able to have an important and strong voice will be able to traverse the next 20 years.

Image: Courtesy Sabyasachi

Image: Courtesy SabyasachiQ. What sort of growth opportunities do you see in the international market?

For the last 20 years, I focussed on India. I had many growth opportunities outside, but I didn’t take any because I wanted to grow my brand in India. I realised that for me to become important as a designer, first in my own eyes, and then for those who matter to me, I need to find my colloquial identity. So I need to have an opinion about my own region and country, and then go international. I’ve done that step by step… I was a Bengali designer who became a national designer. I want to move on and find another path. This time, I’m opening my voice out to the universe for whoever wishes to have me or find me.

Q. Why did you decide to take a break from fashion shows?

One of my friends showed me Instagram and my first reaction was: How can this be for free? I can put an outfit on Instagram where people can see it and start following me. This is like doing your own show. I was getting ready for couture week and decided to stop the show and do it on Instagram. We took photographs and videos, and uploaded them on Instagram. There are hundreds and thousands of people who want to get into my stores, but they’re probably afraid of financial, cultural and language barriers. That’s one of the major reasons why I wanted to do a show on Instagram. I also decided on not giving any exclusives to the press anymore.

Whatever we give is going to be democratic first with the consumer and the press can repost, and there’s been no looking back. Now more and more designers across the country are moving out of fashion weeks and doing this. If I decide to do shows, I’ll do them larger than life and blow them out of proportion. Otherwise, I’m happy to show things on Instagram.

Q. How do you manage to stand out in a competitive space?

By being competitive and by questioning myself as to what value I’m giving consumers. Every year we do this mathematics, like if we increase the price points 10 fold, we increase quality 40 fold. We are not only targeting increasing bottom lines, but also good value. My mother thinks I’m the biggest con artist in this country.

She keeps asking me what is so special about my clothes and why would anyone pay so much money to buy them. I keep asking myself the same question every year. I feel a little bit of that insecurity is nice. Every time I do a collection, I think that nothing’s going to sell. That insecurity, fear and sense of pragmatic practicality kind of helps you stay relevant.

Q. How do you maintain a balance between being a businessman and designer?

If I did everything the way I wanted, I would never sell a piece because in my heart I’m a minimalist. I don’t customise any clothes, but that does not mean that I’m not empathetic to what people want.

Recently I did a collection where there’s a lot of controversy about cleavage. The funny thing is that you put a woman in a bikini and nobody says anything, it is perfectly acceptable, but you put her in a sari with a low-cut blouse, suddenly everyone has a problem. Women as a community are done with people attaching labels on them for the way they dress.

The internet has become a support group for people to discover their own kind of people. But today people have become more confident about their choices. The middle-class is leading this movement, and fashion has now become democratic. There used to be a trickle-down effect in India, where the poor used to dress like the rich, but now you will see that the rich have started dressing like the poor. Because they want to be respected for who they are, not for what they do and what they wear. So fashion is going through a phase right now where the democracy of choice is going to drive luxury. In that case we are all in a good space.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)