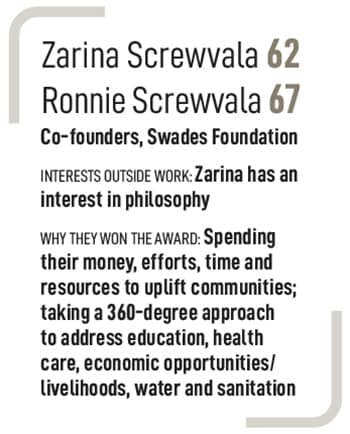

How Zarina and Ronnie Screwvala plan to take the Swades model to new districts

By Divya J Shekhar| Mar 18, 2024

Zarina and Ronnie Screwvala's efforts to lift people out of poverty are showing results in Raigad and Nashik in Maharashtra. Now, they want to take the Swades model to other regions

[CAPTION]Ronnie (in T-shirt) and Zarina Screwvala (in pink kurta) visiting a village in Nashik where they work with the community

Image: Apoorva Salkade For Forbes India[/CAPTION]

[CAPTION]Ronnie (in T-shirt) and Zarina Screwvala (in pink kurta) visiting a village in Nashik where they work with the community

Image: Apoorva Salkade For Forbes India[/CAPTION]

Zarina and Ronnie Screwvala celebrated Republic Day differently this year.

They visited a handful of villages like Hompada, Nandurkipada, Shenvad and Garudeshwar in Nashik, Maharashtra. Their non-profit, Swades Foundation, has been providing grassroots interventions related to education, skilling, health care, water security and livelihoods to the people in these villages since 2019. The meeting on January 26 was for Zarina and Ronnie to have conversations with the community to see the progress of these programmes, and identify what more needs to be done.

_RSS_In one of the villages, a few young Adivasi boys came up to them and confessed that it had taken long for them to trust Zarina and Ronnie, and to accept their help. “They told us that when we had first come to their village [in 2019], they had gone online and researched everything about us,” recalls Zarina, sitting alongside Ronnie at the Swades Foundation office in Mumbai, a few days after the visit. They do not easily trust ‘outsiders’, and rightly so, she continues. “A lot of them have had bad experiences, so they should not trust you. I would encourage all of them to check.”

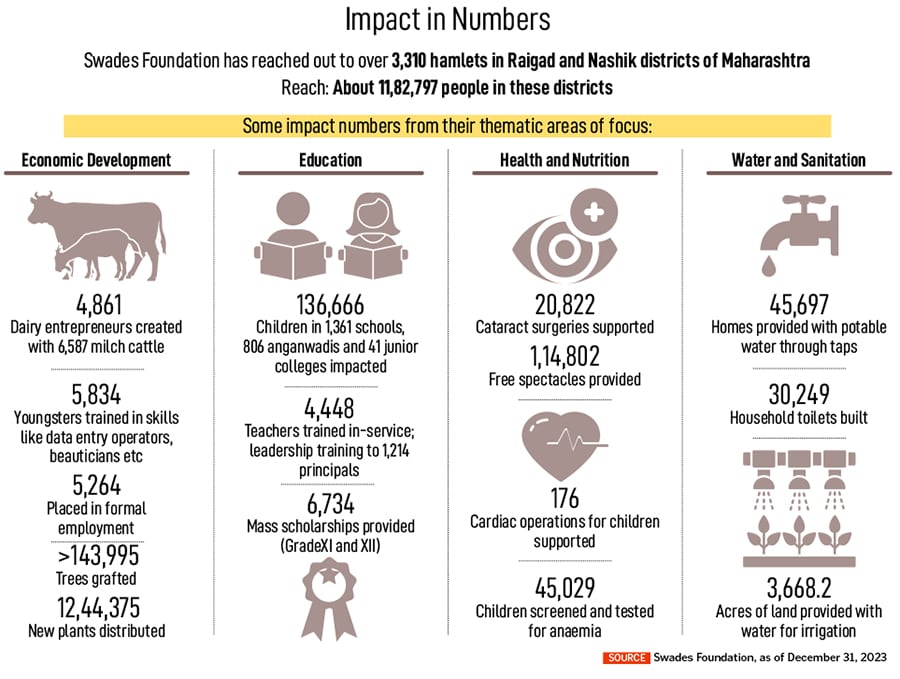

Ronnie, at this point, adds that while the internet and social media have made it easier for people to check and verify facts, the path to earn the rural community’s trust was slow and long-winded when they co-founded Swades a decade ago. Their presence in close to 2,700 villages and hamlets in Nashik and Raigad in Maharashtra today, therefore, has largely been on the backs of word-of-mouth awareness among the people.  From 2013 till date, they have impacted about three quarters of a million people across various villages in these two districts. Their approach has been to go deep, rather than wide. They had launched the non-profit to “test and create a 360-degree, deep intervention model of rural development”, says Zarina.

From 2013 till date, they have impacted about three quarters of a million people across various villages in these two districts. Their approach has been to go deep, rather than wide. They had launched the non-profit to “test and create a 360-degree, deep intervention model of rural development”, says Zarina.

It’s a geographic approach, which includes creating interventions to fulfil needs specific to the local community, from education and health care to water and sanitation, and economic opportunities. Social issues are often interlinked, and it is to understand these nuances that the founders make it a point to visit these villages every two months. In the early days, these visits used to be twice a month.

In fact, the reason Zarina and Ronnie chose Raigad and Nashik is so that they can make these frequent visits, which they say is key to their philanthropic identity. “When you want to be a change agent, you need to be part of the change process,” says Ronnie. “There are enough people giving back in terms of money. There’s also government money. We wanted to also be involved.”

Personal philanthropic donations in India reached ₹4,958 crore in FY23, a 60 percent increase over the previous fiscal, as per the EdelGive Hurun India Philanthropy List 2023, which pegged Zarina and Ronnie’s contributions for the year at ₹22 crore.

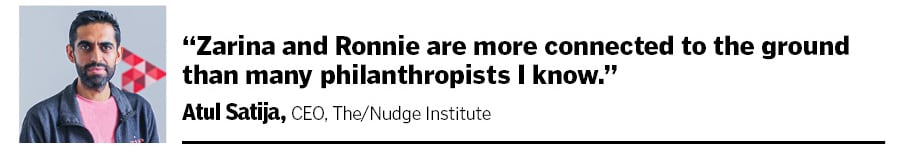

The duo’s approach to philanthropy stands apart from their peers for three key reasons, says Atul Satija, founder and CEO of the non-profit The/Nudge Institute. First is their sharp geographical focus, which he believes is rare among the philanthropic community in India, which tends to focus more on programmes and causes. “When Zarina and Ronnie said they will support communities in Raigad, they took their time to understand and expand their work as per the evolving needs of the people there, through skilling, water, health and other interventions,” Satija explains. “This is a good approach. The government took the same approach many years later, at the national level, by identifying aspirational districts.” [CAPTION]Swades Foundation has been providing grassroots interventions related to education, skilling, health care, water security and livelihoods to the people across various villages in Nashik, Maharashtra, since 2019. They had started with the Raigad distrct a decade ago[/CAPTION]

[CAPTION]Swades Foundation has been providing grassroots interventions related to education, skilling, health care, water security and livelihoods to the people across various villages in Nashik, Maharashtra, since 2019. They had started with the Raigad distrct a decade ago[/CAPTION]

The second reason why Satija finds the approach of the Screwvalas unique is the amount of time they spend on ground and how they are involved with the people. “Many philanthropists understand and have opinions on solutions for the ecosystem, but to spend time on the ground and gain community insights is unique. Very few philanthropists get their hands dirty, and I mean grassroots-level dirty.”

The third reason is the duo’s “desire and evidence for scalability”, Satija says. Zarina and Ronnie agree that scale has always been on their radar, which is why they enter a new region with a strategy to exit within six-seven years. Exit does not mean a complete withdrawal, and the timeline is often flexible, but the team—270-odd strong as on date—goes in with some of direction, Ronnie says. According to him, their approach involves being a catalyst for X number of years and empower people, rather than spending their lifetime in certain geographies.

This has helped Swades now take steps towards expanding to more regions in Maharashtra, as well as explore taking the model to other states. This can either be organically, or through partnerships, says Mangesh Wange, CEO of Swades Foundation. “We are confident of the model and know what works. We have to modify suitably to local contexts, and are now figuring out how to create that,” he says, adding that the long-term vision of the Screwvalas also involves creating an app that communities can use to start implementing interventions with the help of Swades.

Also read: Parth Jindal and the making of an institution of the future

A different kind of scale

Zarina and Ronnie took baby steps towards giving back to society by setting up SHARE (Society to Heal Aid Rejuvenate Educate) as early as 1983. Like most things, they say, this was accidental and their process was not as evolved as it is today. “We had neither the experience, nor the resouces,” says Ronnie. After they co-founded media company UTV in 1990, SHARE found a small space in their large office in Mumbai. “It worked pretty well,” Ronnie recalls, with employees often voluntarily staying back after office hours to be part of social development projects. It was one such employee who suggested they take a look at their uncle’s village in Raigad, where there was water shortage.

After they co-founded media company UTV in 1990, SHARE found a small space in their large office in Mumbai. “It worked pretty well,” Ronnie recalls, with employees often voluntarily staying back after office hours to be part of social development projects. It was one such employee who suggested they take a look at their uncle’s village in Raigad, where there was water shortage. Zarina and Ronnie visited the village with their own ideas. They wanted to fund girl child education. The villagers replied that most girls could not go to school because they did not have water. “So we humbled ourselves, listened to the community about what they want,” says Zarina.

This is when they slowly started understanding the interconnectedness of social issues. For example, they spent three months improving water and sanitation in the village. When the girls started going to school, they realised they needed toilets and sanitation facilities in schools as well, as menstruating girls could not go to school otherwise. Once that was taken care of, a group of women approached Zarina, saying that while they are grateful for the toilets and the water, they now want to do meaningful work to make good use of their time. And that’s when they started looking at livelihoods and self-help groups.

When Zarina and Ronnie divested their shares in UTV to Disney in 2012, Zarina was at a loss about what she should do next. While she contemplated joining Teach for India, Ronnie suggested they should use the money they had acquired to “lift a million people out of poverty”. A year later, SHARE was re-branded as Swades Foundation. The name was inspired by the Shah Rukh Khan-starrer Swades, which Ronnie had co-produced at UTV.

Zarina remembers how they took learnings from the media and tried to implement it at Swades. Like job sheets. “We had extremely detailed sheets of every penny we are going to spend, the process and the reason, all written down,” she says.

They took a lot of advice from people. They also made sure to not take most of the advice. Like one advice they got from many, including government officials, was to just “do one thing, and do it well”.

But Zarina and Ronnie were inspired by the Bangladeshi development organisation BRAC (Building Resources Across Communities), which, broadly, was about working closely with the community, helping resolve their key issues to empower people and create permanent change.

Apart from over 270 employees, Swades also has a cadre of 10,000-odd community volunteers. They create village development committees (VDC) in every hamlet. The members of this committee, 50 percent of whom are women, are trained by the Foundation. They have created over 1,300 VDCs across hamlets in Raigad and Nashik where they operate.

The road ahead

The funding to implement their programmes comes from corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds, high net-worth individuals, and other philanthropic foundations, apart from Zarina and Ronnie’s personal wealth. CSR is the biggest source of funding, the Foundation have multi-year partnerships with various companies, including HSBC, Blue Dart, CDSL, Deutsche Bank, Oracle and Capri Global.For geographical expansion, the fundraising has to go to the next level, says Wange, adding that they are exploring various sources of raising funds, including potentially listing on the social stock exchange by April.

Even over a decade into their philanthropic venture, Zarina and Ronnie retain their willingness to learn, believes Luis Miranda, chairman of non-profit organisations CORO and Centre for Civil Society. “Their mindset has always been ‘Let’s work together’. They respect your organisation and are always open to share experiences and best practices for better outcomes.”

Zarina and Ronnie have been noticing how the window of time needed to create meaningful impact has been getting smaller with every new region they take up, which tells them that their Swades model is working. Now, they are at the cusp of taking a crucial step that will propel Swades to the next chapter of growth: How to let go of the need for proximity.

“At some stage, we’ll have to let go of this restriction that the villages we go to should be near Mumbai, and we will,” Ronnie says. “The institution and the model we have built should be around for another 100 years. From that point of view, we have to figure out the strategy for Swades—that’s the discussion going on.”