Stagnation, losses: Why the economics of startups need a fundamental reset

By Varsha Meghani| Aug 29, 2023

With investor sentiment turning sour, startups are being forced to cut costs, find new revenue streams and focus on profitability

[CAPTION]High quality startups will still raise funds now.

Image: Shutterstock[/CAPTION]

[CAPTION]High quality startups will still raise funds now.

Image: Shutterstock[/CAPTION]

In what Aadit Palicha describes as a “terrible investing market”, Zepto, the speedy delivery startup he co-founded two years ago, managed to raise $200 million at a $1.4 billion valuation, making it India’s first unicorn of 2023.

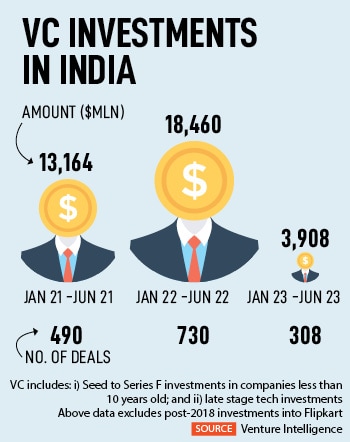

Since the onset of the so-called “funding winter” roughly 20 months ago, Indian startups have been struggling to raise funds. They raised just $3.9 billion in the first half of 2023, 78 percent lower than the same period of last year, according to data provider Venture Intelligence. The funds were raised by only 308 startups, compared with 730 startups in the same period last year.

_RSS_At this run rate, startups may end up raising less than $10 billion this year, a far cry from the record $30 billion garnered in 2021 and $20 billion in 2022.

“High quality startups will still raise funds,” says Pankaj Makkar, managing director at Bertelsmann India Investments, which has backed companies like Licious, Pepperfry and Lendingkart. By “high quality” he means those that are run efficiently with an eye on unit economics, profitability and cash reserves. Palicha, for example, spoke of “real stores” that are generating “real cash” in an earlier interview with Forbes India. Zepto uses a network of dark stores or small warehouses to deliver goods within 20 minutes of a customer placing an order. Annualised revenues now stand at $600-$700 million compared to around $20 million in FY22.

Similarly, Swiggy’s Sriharsha Majesty announced in a blogpost in May that the company’s food delivery business has turned profitable as of March 2023, after factoring in all corporate costs other than employee stock option costs. The company reported a 2.2x jump in revenue to Rs 6,120 crore in FY22, but losses more than doubled to Rs 3,629 crore, according to Venture Intelligence.

“This is a milestone for food delivery globally, not just for us, as Swiggy has become one of the very few global food delivery platforms to achieve profitability in less than nine years since its inception,” Majety, Swiggy’s CEO, wrote. He noted that the company had been building “strong traction” in tier 2 and 3 markets.

He added that Swiggy will continue to make “responsible” and “measured interventions” to fuel further growth in food delivery, and about making “strong progress on the profitability” of Instamart, its three-year-old quick delivery business, which is on track to hit contribution breakeven “in the next few weeks.” There has been no update since on Instamart. Swiggy declined to talk to Forbes India for this story.

“One rarely heard startup founders talk like this earlier on. The funding squeeze and the low tolerance for loss-making unicorns, especially after the Byju’s debacle, has pushed startups to think profits over reckless growth,” says one investor.

The first signs of investor discontent came after Paytm’s flop listing in November 2021. The stock dipped on opening, leading many to question whether startup valuations were justified. This was followed by Zomato’s lack-lustre listing. While stocks such as Paytm, Zomato, Nykaa and Delhivery have recovered since the start of the year, they continue to trade below their IPO price.

Since the onset of the funding winter the startup ecosystem has seen layoffs, delayed stock listings and falling valuations. More than 25,000 employees across 94 startups were fired between January 2022 to June 2023, according to Moneycontrol’s layoff tracker. In fact, the number of layoffs could be much higher as many companies are now resorting to silent layoffs.

In the private tech markets, a pipeline of IPOs have been halted. Sequoia Capital (now Peak XV)-backed Mamaearth delayed its IPO plans, as has Softbank-backed hotel booking startup Oyo. International investors have also internally cut the valuation of Indian startups. Netherlands-headquartered Prosus cut Byju’s valuation to $5.1 billion. Invesco, an Atlanta-based investment firm, slashed Swiggy’s valuation by one-third to $5.5 billion. Japan’s Softbank has not made a single new investment in India in the last 15 to 16 months. Tiger Global, once extremely active, has also stopped splashing cash. Fifty-five of the 74 unicorns (74 percent) incurred a cumulative operating loss of $5.9 billion in FY22, according to Inc42. “It’s pretty bleak out there for growth-stage and mature companies,” says the investor quoted earlier.

Investors have also come to painfully realise that they misjudged the Indian consumption opportunity. Blume Ventures said in an April report that consumption outside the top 30 million Indian households dropped sharply and is driven by a “tiny superuser set”. Despite India’s billion-plus population, consider how Zomato has just 50 million annual transaction users and the ubiquitous UPI has just 260 million, the report added.

Also read: As easy money stops flowing startups shift their focus to profit

Slow and steady

Startup founders with an eye on profitability are eager to make announcements of the progress they have made, however small. Meesho, for example, spoke of turning profit after tax (PAT)-positive in July, helped by a 70 percent drop in customer acquisition costs from roughly Rs 250 two years ago to Rs 50-60 today. Although losses are still mighty at Rs 3,251 crore on revenues of Rs 3,232 crore in FY22, it was a milestone moment for the Prosus, Softbank and Peak XV-backed social commerce startup.“We will see a lot of startups talking of about profitability before this and before that. What matters is whether you have taken all your costs into account,” joked the investor mentioned earlier. “Investors are intelligent enough to see through it.”

A Meesho rival says, “In this business it’s easy to give incentives, book your revenue for the next three months and then claim that you are profitable.” Meesho didn’t respond to Forbes India’s request for comment.

A Meesho rival says, “In this business it’s easy to give incentives, book your revenue for the next three months and then claim that you are profitable.” Meesho didn’t respond to Forbes India’s request for comment. Other startups are cutting costs and finding new revenue streams to achieve profitability. Take the case of ShareChat. While revenues in FY22 rose 331 percent to Rs 419 crore, losses nearly doubled to Rs 2,988 crore in FY22, according to Venture Intelligence.

“These numbers are dated,” points out Manohar Singh Charan, ShareChat’s CFO. In the period that followed, the company has cut costs by 80 percent, he says. Marketing expenses have been halted in entirety, while cloud infrastructure costs—the second biggest expense for the company—have been reduced by half. “We’ve been able to do this while still not losing out on user growth by making our artificial intelligence [AI] recommendation engine more and more sophisticated. Users will keep flocking to our platforms [ShareChat as well as the short video app Moj, launched in the wake of the TikTok ban in India in June 2020] if they are continuously shown the content they want to see. It makes our organic user pull very strong,” he says.

Second, ShareChat has also innovated “beyond ads” to find new streams of revenue. For instance, it has started monetising what Charan calls “WhatsApp sharing”. ShareChat is the biggest originator of WhatsApp shares in the country, claims Charan. So, it’s now reaching out to advertisers to add their logos on to such shared memes or videos. Livestreaming is set to be another big revenue earner for the platform. For instance, an astrologer from Haridwar conducts a livestream on the Moj app, and his followers can donate money to him in the form of ‘dakshina’, a portion of which will be taken by the platform.

“We are like a B2C and B2B business. Our expenses are B2C in nature because you must invest in technology and marketing to acquire customers, but our revenues are B2B as they come from advertisers. So it’s harder for us to achieve profitability,” says Charan. Hence the need to innovate. ShareChat is on track to achieve contribution breakeven by December 2023, while Moj will achieve that by mid-next year, he adds.

Also read: Hoopla and Hubris: Why Indian startups are coming undone

What next?

“The worst is not behind us,” says Makkar. “The funding winter occurred because the public market for tech stocks in the US fell the unsustainable highs that abundant capital had induced. That led private company multiples in the US to collapse and the knock-on effect was felt in India. So, US market stress caused investors to be cautious in other parts of the world, including India.”“Until the situation in the US public and private markets doesn’t ease and global investors don’t return with the same enthusiasm, we won’t see any dramatic change in India,” he adds. Macroeconomic variables like high interest rates and inflation have further weighed on the investment climate in India and elsewhere.

So, while some startups may fall by the wayside, others may consolidate and yet others might push through and ride out this long, painful downturn. In the coming weeks as startups begin revealing their FY23 results, investors will be watching closely. “But…” as the investor quoted earlier says, “…they will be expecting more pain before profits.”