Can GoKwik keep up its heady growth and erase losses?

By Rajiv Singh| Nov 29, 2022

Ecommerce enablement startup GoKwik has got off to a zippy start. Now it's time to see if it can sustain the momentum

[CAPTION]

(From left) Ankush Talwar, Chirag Taneja and Vivek Bajpai, co-founders of GoKwik

Image: Amit Verma[/CAPTION]

[CAPTION]

(From left) Ankush Talwar, Chirag Taneja and Vivek Bajpai, co-founders of GoKwik

Image: Amit Verma[/CAPTION]

“It’s a necessary devil,” reckons Chirag Taneja. “You can’t live with it, and you can’t live without it,” says the mechanical engineer, alluding to CoD (cash on delivery), a mode of payment wherein a customer buys a product online, but pays in cash when the order gets delivered. Taneja knows a thing or two about the ‘devil’. After all, the former chief revenue officer of Bombay Shaving Company has had umpteen close shaves with the devil before donning the hat of second-time founder. An MBA grad from FMS Delhi, Taneja started his professional stint with Maruti in 2004, went on to work for data analytics firm Inductis, followed by almost a six-year tenure at Yes Bank, before taking the entrepreneurial plunge in 2015 by co-founding Ketchupp, an online search engine for food discovery.

_RSS_The rookie founder did have a saucy beginning. Back then, Zomato and the likes were trying to solve the problem of ‘where to eat’. Taneja took a contrarian bet, and decided to fix ‘what to eat’. The business scaled reasonably over the next three years: Eight cities, 3 million users a month, and clocking close to ₹20 crore a year. There was a glitch, though. Taneja was caught between the devil and the deep sea. Rising revenue and scale were happening largely on the back of advertisement revenue, which the founder never wanted. “After all, Ketchupp was not supposed to be an ad-driven business,” he recounts, underlining that ad-revenue had become a necessary devil.

The other option of doing a Swiggy was not an option at all. “We had missed that bus,” says Taneja, adding that Ketchupp was getting enough traffic and was passing orders to Swiggy and Zomato. “I didn’t want to get into an operational business,” he says. Taneja, subsequently, sold the company to CarToq in 2018. In hindsight, from a business perspective, he confesses, to not get into the food delivery space was a wrong call. “But I wanted to build tech, and no longer wanted to dance with the devil,” he adds.

Fast forward to November 2022. Four years later, and two years after co-founding his second venture, GoKwik—an ecommerce enablement startup—Taneja again talks about CoD, another ‘necessary devil’. Out of 100 orders on CoD, around 30 are failed deliveries. What this means is simple. The goods have to be returned to the seller—in technical parlance, it’s known as RTO (return to origin). What this also means is a heavy financial cost borne by the retailers, points out Taneja, who increasingly started realising during his stint at Bombay Shaving Company that a massive chunk of ecommerce would soon happen outside the likes of the Amazons and Flipkarts of the world. “Well, that was the big opportunity,” he says.

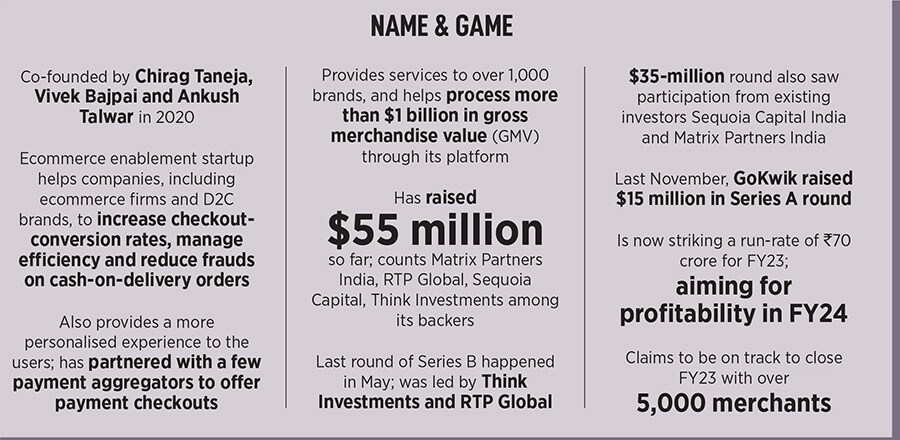

Opportunity, though, came with a massive challenge. With CoD remaining the predominant mode of payment, retailers were still reluctantly living with the ‘necessary devil’. In spite of a quick uptick in digital payments and UPI over the last few years, the share of CoD orders stood at a staggering 47 percent for the first phase of the online festive sale in 2022, according to a recent report by Redseer, a homegrown strategy consulting firm. Taneja knew that in order to tame the devil, he needed to arm himself with tech and data science capabilities. Consequently, he teamed with Vivek Bajpai and Ankush Talwar to roll out GoKwik. The idea was to increase checkout-conversion rates, manage efficiency and reduce frauds on CoD orders.

The job seemed easy. But it was not. Taneja and his gang realised that the devil lay in details. The first hurdle was to convince a battery of die-hard sceptics, experts and funders. “How can a bunch of rookies solve what veterans failed for years?” asked scores of venture capitalists. “To fix RTO, you need loads of data. We had more than that, but still we struggle,” commented a data scientist working with one of the big ecommerce players. “Forget it. You won’t be able to crack it,” he suggested. Merchants too sounded cynical. The model looks good on paper and the intent too is sincere. “But I don’t think it will change the outcome,” he quipped.

Also read: 100 to Watch: 11 Indian companies finding solutions to real-world problems

Taneja stayed adamant, and was at his persuasive best. “Everybody can get the ingredients,” he tried to argue, conceding that access to data is the easiest part. “But only a chef knows what to make of the ingredients,” he reasoned, adding that he was trying to solve the problem at the source. He explains. A high RTO has always been perceived to be a logistics problem. ‘Change the logistics partner and fix the leaking bucket’ has been the mantra. The diagnosis, Taneja stresses, was wrong. Data, he underlines, suggested that RTO has nothing to do with logistics. “It’s a consumer-intent problem, which is an outcome of impulse purchase,” he says. So how do you gauge intent? In fact, can intent be predicted? This is what Taneja tried to do. “I wanted to be in the business of predicting consumer intent,” he underlines. The first step was to assure jittery retailers. GoKwik offered to cover all the risks involved in CoD orders. “If we get it wrong, we will refund the entire reverse logistics cost,” he promised to the merchants. Banking on an extensive set of parameters powered by AI and data science team, GoKwik rolled out its innings officially from January 2021.

So how do you gauge intent? In fact, can intent be predicted? This is what Taneja tried to do. “I wanted to be in the business of predicting consumer intent,” he underlines. The first step was to assure jittery retailers. GoKwik offered to cover all the risks involved in CoD orders. “If we get it wrong, we will refund the entire reverse logistics cost,” he promised to the merchants. Banking on an extensive set of parameters powered by AI and data science team, GoKwik rolled out its innings officially from January 2021.

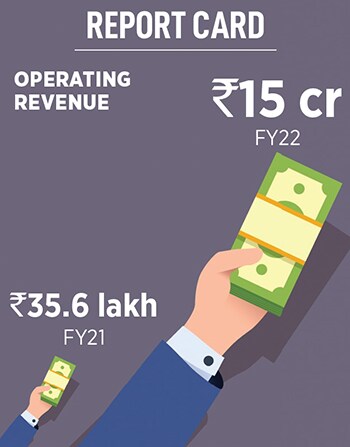

The outcome for the first truncated fiscal was far from encouraging. GoKwik’s loss was double its operating revenue: ₹76 lakh versus ₹35.6 lakh. Taneja was not disheartened. Reason: He knew the magic would come at a scale. Earlier, he underlines, the startup was able to predict with 90 percent accuracy for 1 percent people. Twelve months later, the dynamics changed. “Now, we are able to predict 90 percent accuracy for 5 percent of people,” he says. His claims are matched by the pace at which operating revenue has raced: From ₹35.6 lakh to ₹15 crore. Though the losses too have surged from ₹76 lakh to ₹11 crore in FY22, Taneja predicts that the startup is on track to hit profitability in FY24. “We are now striking a revenue run rate of ₹70 crore for FY23,” he claims.

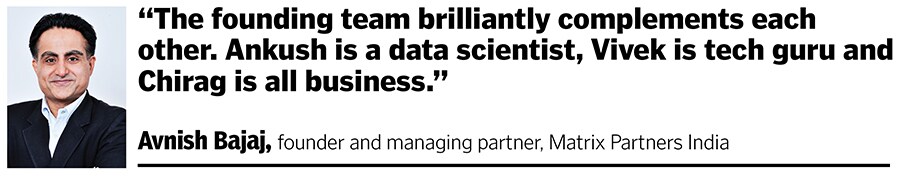

The backers are delighted with the brisk pace of growth. “We are impressed with the company’s strong start,” contends Ashish Agarwal, managing director at Sequoia India, which led GoKwik’s Series A round of funding in November last year.  GoKwik has raised $55 million so far, and counts Matrix Partners India, RTP Global and Think Investments among its other funders. GoKwik, Agarwal underlines, is one of the very few companies globally that sits beautifully at a strategic junction for ecommerce. What has worked for the team is its success in solving a problem which defied solutions for over a decade.

GoKwik has raised $55 million so far, and counts Matrix Partners India, RTP Global and Think Investments among its other funders. GoKwik, Agarwal underlines, is one of the very few companies globally that sits beautifully at a strategic junction for ecommerce. What has worked for the team is its success in solving a problem which defied solutions for over a decade.

Agarwal explains. CoD has become more acute with wider ecommerce penetration. About 70 percent of all ecommerce orders are still CoD and 25-35 percent of them are returned. “This is a huge money sink for ecommerce merchants,” he reckons. GoKwik’s first product was a return risk score coupled with an insurance solution. It assesses an order’s return risk, helping brands weed out high risk and limit payment options to prepaid for medium-risk customers. As more brands adopt GoKwik, Agarwal underlines, it deepens the platform’s network effects. “By owning checkout, GoKwik is uniquely positioned to enable merchants across payments, loyalty, fulfilment, marketing and financing,” he says.

Though GoKwik has had a hockey-stick growth, it still has a host of issues to contend with. One of the challenges emanates from building the startup remotely. The pandemic baby has over 150 employees working from across 47 cities. “We don’t have an office, and we kept on adding people,” he says. A flip side could be cultural issues among the burgeoning team. The second challenge is bringing down losses, which have bloated at a furious pace.

Taneja reckons that bottom line would fall in place as the business expands and grows even bigger in scale. “Our venture is a heavy network-effect business,” he says, adding that the venture is likely to reach an inflection point in scale by April next year.

Another challenge could be to take a calibrated step in expanding overseas. Though the global opportunity is massive—Middle East, Indonesia and a bunch of countries exhibit similar customer behaviour and problem—stabilising business in India and then hunting for greener pastures abroad would do a world of good.

Taneja, though, prefers to look at the big picture. “The opportunity with us is truly global,” he says. The flip side for most of the founders, he confesses, is the perennial-haunting question: Fail toh nahin ho jayenge (what if we fail). “For me the question is: What if we pass with flying colours,” he says, sounding thrilled with the prospect of disproportionate outcome. “It’s a long way to go. We are still at Day Zero. We need to keep building,” he signs off.