Copyright 2019, Forbesindia.com

Drones are becoming the Indian farmer's new best friend

By Naini Thaker| Sep 2, 2022

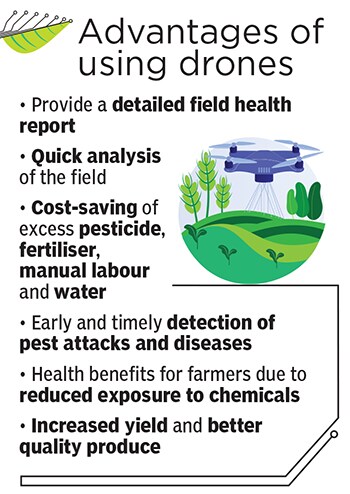

Drones help save time, cost, increase yield and productivity but a lot more needs to be done to make the most of the technology

[CAPTION]The surge in drone adoption in the agri sector has brought with it a host of benefits to farmers[/CAPTION]

[CAPTION]The surge in drone adoption in the agri sector has brought with it a host of benefits to farmers[/CAPTION]

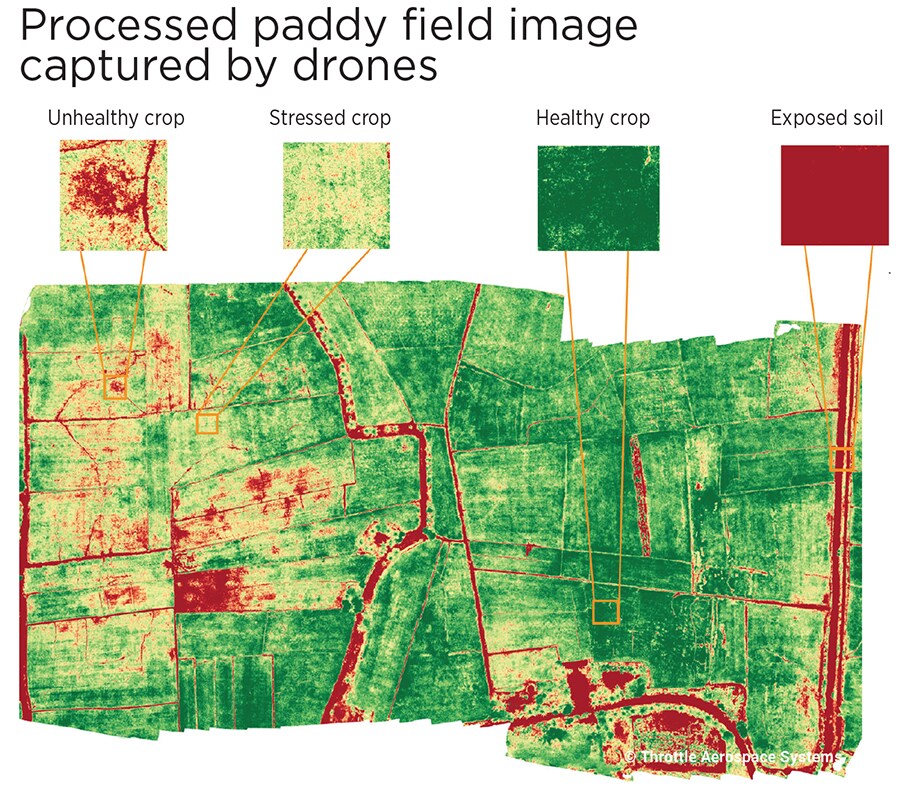

Kerala’s Kuttanad—a region covering Alappuzha, Kottayam and Pathanamthitta districts—is one of the few places in the world where farming takes place below sea level, with paddy fields 1.2 m to 3 m below sea level. In 2016, the Kerala government appointed drone manufacturer Throttle Aerospace Systems (TAS) to analyse 25 acres of paddy fields in Kuttanad, where water salinity is extremely high.

The objective, recalls Nagendran Kandasamy, founder and CEO of TAS, was, “to create a detailed field health report, along with a georeferenced map of the entire field, via our drones”. Various parameters—such as altitude, weather, wind and area to be covered—were entered into the drone. After about four hours of flying time, the drones produced near-infrared (NIR) images that mapped the field based on the health of the crop—ranging from ‘unhealthy crop’, ‘stressed crop’ to ‘healthy crop’ and ‘exposed soil’. “This [NIR] data allows one to precisely quantify the coverage, which is tough to accurately gauge with visible-range information,” adds Kandasamy.

This field information and analysis provided by TAS helped farmers estimate crop yields a lot faster, optimise plant inputs, understand water flow and quantity, and a lot more. “Manually covering this land, especially below sea level, would take a lot of time and labour, with potentially not very accurate results. With the data we’ve provided to the farmers, they can focus on the area marked in red, which needs the most attention,” he explains.

_RSS_This is only one of the many impact case studies of how valuable drones can be in agriculture. The government is also recognising this. During Budget 2022, Union Minister of Finance Nirmala Sitharaman said, “Use of ‘Kisan Drones’ will be promoted for crop assessment, digitisation of land records, spraying of insecticides and nutrients.”

During a conference on Kisan Drones in May, Minister of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare Narendra Singh Tomar announced that the government will be providing 50 percent or a maximum of Rs 5 lakh subsidy to SC-ST, small and marginal, women and farmers of Northeast states to buy drones. For others, financial assistance will be given up to 40 percent or a maximum of Rs 4 lakh.

Outside of agriculture, adoption of drones has seen a massive jump, especially since the new liberal drone policy, Drone Rules 2021. According to an estimate by the Ministry of Civil Aviation, India’s drone sector will achieve a turnover of Rs12,000-15,000 crore by 2026, from about Rs80 crore currently. There are 220 drone startups in India, with the number jumping by 34.4 percent between August 2021 and February 2022.

The drone advantage

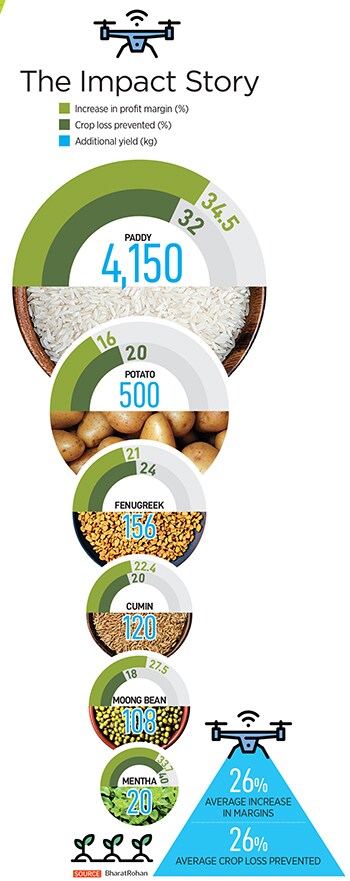

Amandeep Panwar and Rishabh Choudhary, founders of BharatRohan, realised that almost every farmer faces issues related to pest attacks and diseases on their crops. “However, those remain undetected until it reaches the economic threshold level (ETL), or until there is visible damage to the crop. Farmers apply pesticides only after the infestation crosses the economic injury level (EIL),” explains Panwar. Due to these issues, there is almost a 15 to 25 percent yield loss every year.

[CAPTION]Agnishwar Jayaprakash, founder and CEO of Garuda Aerospace[/CAPTION]

[CAPTION]Agnishwar Jayaprakash, founder and CEO of Garuda Aerospace[/CAPTION]Satyendra Babu, a 40-year-old farmer in Bidare in the Tumkur district of Karnataka, grows mango, areca nut and coconut, and has been using TAS drones for a few months. “One of the biggest issues we faced was labour. Since I started using drones for pesticide spraying, I no longer need to worry,” he explains. The cost of pesticides is also quite high. With drones, his pesticide usage has gone down significantly. “My total cost has reduced by almost 50 percent. I pay about Rs 2,500 per spray for using drones to spray pesticide on my 10 acres of land.”

Agnishwar Jayaprakash, founder and CEO of Garuda Aerospace, says, “For about 40 acres of farmland, each acre needs to be sprayed eight times a year. Farmers pay Rs400 per acre, per spray for it. This means they are spending close to Rs 20,000 crore each year.”

Abhishek Burman, co-founder and CEO of General Aeronautics, explains the real problem: “When farmers manually manage pests and disease, the efficiency is no more than 10 percent. Additionally, each spray on one acre needs 200 litres of water, which is too much wastage. Since the efficiencies are poor, farmers over-spray and reduce soil fertility.” Additionally, agrochemicals can cause multiple health issues.

Due to all these issues, the maximum residue limits (MRL)—the highest level of a pesticide residue legally tolerated—has also been getting affected. Burman adds, “A large percent of the world’s cumin is exported by India. Cumin exports have decreased by 13 percent in 2021 due to MRL standards world over. Most countries are demanding pesticide residue-free cumin.” According to FISS data, cumin exports decreased by 13 percent in 2021 to 2.216 lakh tonnes from 2.548 lakh tonnes the previous year. Using drones can lead to controlling MRLs, about 20 percent increase in food productivity, 70 percent less pesticide, 97 percent water saving and 30x efficiency. In a span of 10 to 15 minutes, a drone can cover one acre, which means a three- to four-hour manual job can be done in five minutes.

Various use cases

Kandasamy came up with the concept of TAS in 2014, when he saw someone on Huntington Beach in California, fishing with the use of drones. In 2016, after TAS did the Kerala government project, it started working heavily in the space of agriculture, where it works not only with drone service providers but also with clients such as JK Insurance.

“Crop insurance is very important. So, insurance companies use drones to cross-check crop yield, before handing out settlements to farmers,” explains Kandasamy. There are research institutes such as the University of Agricultural Sciences in Bengaluru that use TAS drones to gauge data and analytics and provide it free of cost to farmers.

Most drones in the agri space are sold to drone service providers who work with farmers, either leasing or renting them, and providing farmers with smartphones or tablets to access the software. Garuda Aerospace has been connecting with farmers directly. A drone made by an Indian manufacturer is priced at Rs 4 to Rs 5 lakh, and it costs Rs 2 to Rs 3 lakh to manufacture it. The standard industry margin is 25 to 30 percent.

Jayaprakash says, “Farmers are never going to buy the drone; they will always use it as a service.” The company has pre-booked 2,500 drones and sold 270-280 of them. Drone service providers could include rural entrepreneurs, FPOs, FPCs, collectives or associations.

For two-and-a-half years, Garuda worked on many pilot projects with the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and state agriculture universities, deploying projects in over 320 Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs). “These nodal agencies help in providing feedback and making recommendations for what the farmer wants. Through these projects we realised that every region and crop needs to be treated differently. For instance, Maharashtra has a fungus problem and Tamil Nadu has a rodent problem.” Garuda makes a 24 percent margin on every drone sold, and a 15 percent margin on every acre sprayed.

BharatRohan has two models: One where it works directly with farmers, and the other where it sells produce to clients from industries like FMCG, modern retail and exporters in domestic and international markets. “For the first one, we provide an end-to-end decision support system (DSS) for farmers. Drones mounted with hyperspectral cameras monitor crops every few days, and suggest measures in case of issues,” says Panwar. Farmers working with BharatRohan have saved Rs3,600 per acre and their yield has increased from 50 kg to 70 kg per acre. This increase has resulted in additional income of around Rs 20,000 per acre.

Similarly, Aarav Unmanned Systems (AUS) has been using RGB Mapping, data from which can help with farm boundary detection and designing piped irrigation networks. “We also work with multispectral mapping technologies to understand more about plant health. Plants reflect NIR more than any visible energy bands, and studying these wavelengths can tell us about plant health,” adds Singh.

Similarly, Aarav Unmanned Systems (AUS) has been using RGB Mapping, data from which can help with farm boundary detection and designing piped irrigation networks. “We also work with multispectral mapping technologies to understand more about plant health. Plants reflect NIR more than any visible energy bands, and studying these wavelengths can tell us about plant health,” adds Singh.Unlike other drone manufacturers, Skylark Drones focuses on the software side. It works closely with seed company Mahyco to help it estimate yield for some of their plantations. “Our software allows drones to count individual plants in the most accurate manner. Each plant is given its own unique ID and it also runs diagnostics of the plant’s health,” explains Mughilan Thiru Ramasamy, co-founder and CEO of Skylark Drones. The company is also working on pilots to spray as much as needed by each specific plant. “With agri, having a well-established network for distribution is key. This was a major challenge for us, but having a partner like Mahyco helps in providing the last-mile training and education,” he adds.

What needs to change?

On the regulatory front, there have been a lot of positive changes for the industry after the Drone Rules 2021.

However, on the tech front, it is struggling when it comes to the high costs of lithium ion and lithium polymer batteries. “The battery only comes for 500 cycles—one take-off and one landing is one cycle. One battery pair costs Rs 25,000-30,000 and there are almost no manufacturers in India; most batteries are imported,” Kandasamy explains.

Panwar of BharatRohan believes there is still a lack of accessibility to drone manufacturers in some states: “The government should identify drone companies in respective states and help local FPCs avail services and products through the subsidies, along with financing opportunities through the Agriculture investment Fund (AIF).”

A major setback for the drone sector is the lack of component manufacturers in India; even now, 30 percent of components are imported. Players like Garuda Aerospace are planning to start component manufacturing via tie-ups with large players, such as Wipro and HAL. “The government is hoping to make India the number one ecosystem for drones by 2030, but this can only happen with the right amount of technological innovation,” says Burman.

With a focus on drone adoption in the agri sector, there is a potential for over 100,000 job opportunities being created in three years. “Currently, there is a huge shortage of drone pilots and skilled talent for the design and manufacture of drones. There is a big mismatch between the supply and demand of talent in this space,” says Singh of Aarav Unmanned Systems.

One major change that drones have brought about is giving the younger generation a “dignity of labour”. Adds Jayaprakash, “Most next-generation farmers don’t want to become farmers. Drone-based solutions give them a tag of a ‘technocrat’ and they feel more respected. I think going forward this will change agriculture as we know it.”