Flush with funds: Can startups revive India's economy?

By Mansvini Kaushik, Anubhuti Matta| Aug 31, 2021

When older companies started downsizing or shutting shop during the pandemic, startups continued to gain momentum. In 2021 alone, startups have raised more than $20 billion in funding

Startups are a better bet over traditional companies as it gives employees the chance to experiment: Says Charu Gupta, Vice president, marketing and strategy planning at edtech

Startups are a better bet over traditional companies as it gives employees the chance to experiment: Says Charu Gupta, Vice president, marketing and strategy planning at edtech

startup Byju’s

For two years, Nagarjuna Cherivirala worked at a political strategy multinational company, but found little scope to make decisions or for personal development. Frustrated, he quit and decided to join a startup. “Startups, I feel, are the best platform to grow as a professional,” says the 27-year-old who, in 2019, joined Lokal, a hyperlocal regional language content application providing district-level news, jobs, and classifieds. “At Lokal, I have been actively devising strategies, taking decisions for the team, and doing much more than the scope of my role.” Today, he is the head of operations-classified business at Lokal and works with all the departments. “I get to experience every vertical, be it marketing, content management or market research.”

Charu Gupta says startups are a better bet over traditional companies as it gives employees the chance to experiment. “Even with 12 years of work experience, while looking for a job during the pandemic, I felt employers were taking candidates like me for granted. They would change the scope of work, not pay as per market standards, compromise the function or roles, and even the number of holidays,” says Gupta, who is now vice president, marketing and strategy planning at edtech startup Byju’s. “Now, working with a startup of this scale, not only do I have flexibility, but also the opportunity to learn by doing more than what is in my job description.”

_RSS_What stands out in these cases is the zeal among professionals to find growth opportunities in startups that are increasingly offering better options with roles that are more challenging and flexible. Also, during the Covid-19 pandemic, when older companies started downsizing or shutting shop, startups continued to gain momentum. In 2021 alone, startups have raised more than $20 billion in funding, and more than 20 of them turned unicorn. This not only means new business opportunities, but also the creation of jobs across various sectors.

Education is one of them. With the rise of online learning, stakeholders, including parents and teachers, have undergone a change in mindset, and have accepted the integration of technology in learning. Consequently, the sector saw user growth, attracted venture capitalist (VC) funding, and generated a host of employment opportunities. Unacademy, for instance, increased its workforce from 600 in April 2020 to 4,000 this April; upGrad grew from 500 to 2,000 during the same period; and Byju's hired more than 5,000 employees, with plans to hire up to 8,000 more.

“While some job descriptions have continued as is, a couple of roles have been altered with shifting demands,” says Pravin Prakash, chief people officer at Byju’s. “With remote working in play, the jobs of tomorrow will be talent-driven, location agnostic, and tailor-made, basis skill and specialty.”

The Indian edtech sector has seen more investments—$2.1 billion—in 2020, than in the last 10 years combined ($1.7 billion), according to reports. “This shows the immense speed at which the sector is growing,” says Mayank Kumar, co-founder and MD, upGrad. “Therefore, the edtech space, from an employment standpoint, is surely a sunrise sector and is one of the key drivers of the job market in 2021. With the rising demand for online education across geographies, we are sure to witness high employment growth in the country."

Covid-19 has also put the spotlight on health tech, with customers adapting to digital modes of treatment, and telemedicine becoming more acceptable. “The future of health care in India looks bright as more and more startups are trying to solve age-old issues in the system,” says Mudit Dandwate, CEO and co-founder of Dozee, a contactless patient monitoring and early-warning system. “We feel employment in this sector is growing at a rapid pace as there is a realisation of the need for a robust health care system. We will see significant growth in the number of jobs created and people employed in this sector.”

The health tech industry is expected to touch $5 billion by 2023, and witness a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 39 percent, according to management consulting firm Praxis and IAMAI.

Dozee, which started with two employees in 2015, now has 160, up from 30 last year. They have hired across data science, research and development (R&D), products and technology, operations, sales, business, finance and HR. “Startups are solving major problems in India in the fintech, health, logistics, education and ecommerce space,” says Dandwate. “We are doing R&D activities, expanding pan-India, and planning to install 50,000 devices in the next year. We would need to increase our workforce across India as well.”  At Niramai, which built Thermalytix, an artificial intelligence (AI)-based thermal imaging device to help detect early-stage breast cancer, the team has grown from two in January 2016, when it was founded, to 65 now; it hired 22 people last year.

At Niramai, which built Thermalytix, an artificial intelligence (AI)-based thermal imaging device to help detect early-stage breast cancer, the team has grown from two in January 2016, when it was founded, to 65 now; it hired 22 people last year.

Dr Geetha Manjunath, founder, CEO and CTO of Niramai, says the company is attracting a lot of resumes for roles in the data scientist and research engineer departments, in addition to those for business development, sales and senior CXO positions. “I believe the time has come for health care startups to scale. So, we need to keep accelerating irrespective of the pandemic or other environmental conditions, and find ways to circumvent hurdles,” she says.

The shift in consumer habits towards digital purchases has meant an unprecedented growth in the supply chain space as well. To serve this increased demand, Ecom Express, a technology-enabled logistics solutions provider added over 12,000 employees in the past year, taking the team size to 45,000 people. Owing to the transformations and changes led by investments, the startup industry is creating enormous employment opportunities, says Saurabh Deep Singla, EVP and CHRO, Ecom Express.

“For instance, we have more than 100 women working at our facility in Bilaspur town, Haryana. Some of them fund their families’ education, others pay their rent. Similarly, Tauru, a village near which our warehouse is located, was once considered to be among India’s most backward. But with employment in ecommerce logistics and warehousing cropping up there, locals are getting jobs and urban facilities in just a few years,” says Singla.

He foresees a huge requirement of logistics resources in the country. “A number of trends will drive this growth and most of these will involve the adoption of technology. Thus, while the demand for manpower will remain, the sector will also see a lot of opportunities for niche skill sets around robotics, technology, data science and analytics,” Singla adds.

Logistics company Ecom Express has opened up jobs for women in remote places, like Manipur

Logistics company Ecom Express has opened up jobs for women in remote places, like Manipur

Also born during the pandemic were six new software-as-a-service (SaaS) unicorns. A recent SaaSBOOMi study by McKinsey & Company noted that not only do Indian SaaS companies have the potential to create $1 trillion in value but also create half a million new jobs by 2030.

One budding SaaS player, Freshworks, which was founded in 2010, has scaled over the years to 13 global locations with over 4,100 employees. Despite the pandemic last year, the team has been growing, says Suman Gopalan, CHRO. Freshworks hired over 1,000 people globally and on-boarded them remotely.

“The pandemic has been a strong reason for digitisation, with businesses looking to understand their customers, and create the best possible virtual experience for them. That’s where companies like ours come in,” says Gopalan. “The pandemic has disrupted economic activity, and digital technologies have helped many businesses navigate the crisis. We believe technology holds the key to recovery through job creation, especially among startups and small businesses.”

India’s fintech market is the world’s fastest-growing, with 67 percent of the more than 2,100 fintech entities in operation being set up in the last five years. Razorpay, an online payment platform, employs more than 1,600 people; in 2020 it hired more than 500 people, and so far in 2021 it has hired more than 600. “The hiring rate is not going to slow down anytime soon,” says Chitbhanu Nagri, senior vice president, people operations, Razorpay.

The fintech industry is valued at $50-60 billion, and is expected to be worth $150-160 billion by 2025, according to a Boston Consulting Group report released in March 2021.

Nagri says that, in late 2020, there was a 10x spike in the number of applicants. “Fintech startups are increasingly becoming the preferred platform for applicants since this is one industry that is free of the pandemic-induced uncertainties in employment,” he says, adding that three in 10 job applicants in late 2020 were out of work or had a gap in employment. “While hiring, we look for a cultural fit, an entrepreneurial spirit, a consumer-centric approach, and innovative ideas and solutions,” says Nagri. “These things aren’t usually what an established company focuses on while hiring.”

The non-metro focus

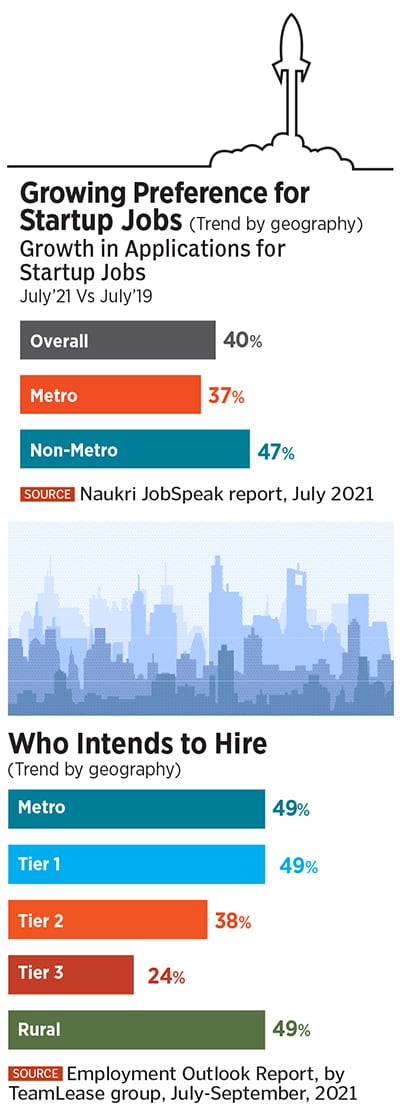

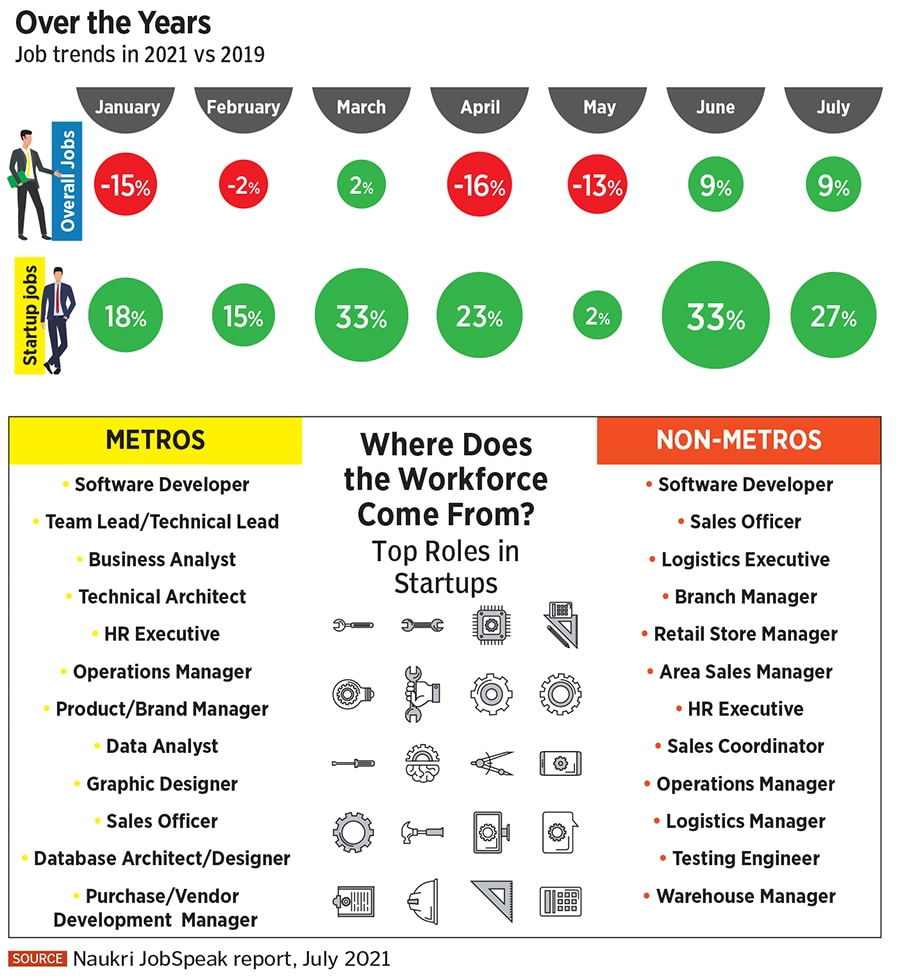

An analysis by Dun & Bradstreet indicates that the agricultural sector has recorded the highest growth in new business registrations, with 12,368 registrations in FY21 compared to 6,107 in FY20. Additionally, in July 2021, there has been a 47 percent increase in non-metro applicants for startup jobs, compared to July 2019, according to a report by Naukri.com, signalling the opening up of employment opportunities in rural areas.

For example, Lokal, founded in 2018 and catering to tier 2 and 3 cities, has witnessed a substantial rise in job seekers and providers on its platform. “Money isn’t the only thing people are looking for from jobs in small towns; the quality of the job is. There is a hunger to excel among young professionals,” says Jani Pasha, co-founder of Lokal.

Startups catering to and operating in small towns, generating employment and creating growth opportunities, have increased manifolds.

“Of late, we have witnessed a rise in startups catering to rural India. There are viable startup solutions that have been introduced by entrepreneurs. A testament to this is the growing number of agri-based and fintech startups that have taken up the challenge,” says Rituparna Chakraborty, co-founder and executive vice president of TeamLease Services, a human resource company.

Take, for instance, Meesho, a social ecommerce company that enables small businesses and individuals to start their online stores via social media. As of 2021, it on-boarded over 15 million entrepreneurs, “enabling women across India to become financially independent”, says Ashish Kumar Singh, CHRO. He says that not only did the business grow rapidly, but they also launched a mini startup called Farmiso, dedicated to reselling fresh farm produce. “Meesho and Farmiso have empowered people in many rural pockets to run their own businesses online. Our goal is to democratise internet commerce, and help small, medium, and individual business owners become financially stable.”

The gig culture

According to a TeamLease report, the gig economy can serve up to 90 million jobs in India’s non-farm sectors, with a potential to add 1.25 percent to the GDP over the long term.

Urban Company, a home service provider, has more than 32,000 professionals, and more than 1,300 full-time staff. “We are scaling our services across cities and categories, and hiring more professionals to fuel our growth,” says Neha Mathur, senior vice president, human resources. “Some of our most critical charters in both business teams and technology are led by high-performing women. The aim is to build a diverse organisation that is representative of our marketplace.”

While gig jobs provide more freedom and discretion for professionals, there are multiple issues like low wages, lack of social security, working conditions, and employee rights that need active governmental intervention. Arun Singh, global chief economist, Dun and Bradstreet, believes that if steps are taken to actively address these concerns, the gig economy could be a significant driver of growth for India. “By exploiting economies of scale, digital platforms can match demand and supply in the most cost-effective manner. This translates to lower unit costs for platforms and higher unit pay for workers. India has also built a strong public digital infrastructure, which is a key component of the gig ecosystem.”

Will startups help the economy?

India is the world’s third largest startup hub, and despite the pandemic, the total number of business registrations in FY21 reached a record high, according to Dun & Bradstreet’s analysis. The birth rate of new businesses was 11.6 percent in FY21, up from 10.2 percent in FY20.

“These new businesses helped absorb some of the workforce that was displaced by the pandemic, and are therefore important to economic revival. Startups account for a disproportionate share of economic growth,” says Singh of Dun & Bradstreet.

The July 2021 Naukri JobSpeak report indicates a similar trend of continued hiring activity across the board. “The growth of jobs in non-metros is very aggressive. Compared to H1 of 2019, openings in non-metro cities have grown by 24 percent in non-metros, and 15 percent in metros. The overall hiring activity in India indicates a strong revival of economic growth and a sustained recovery from the impact of Covid-19,” says Pawan Goyal, chief business officer, Naukri.com.

Kumar of upGrad agrees. “The hiring spree at startups has a direct correlation with the country’s GDP and will help the economy revive. They are responsible for creating more jobs, thus accelerating employment.”

Startups, however, have high mortality and only some will survive and grow in the long term. “But this mortality rate cannot be a case against resurgence. Some startups may not sustain themselves in the long run, but the country needs to go through this process,” says Chakraborty of TeamLease. “Although the country has not been able to create an organisation of the stature of Google and Facebook, the momentum should not be lost.”