Copyright 2019, Forbesindia.com

How Kurkure kept its crunch for 20 years

By Rajiv Singh| Oct 26, 2020

PepsiCo India's first homegrown brand has safeguarded its positioning in the extruded snacks market for over two decades, but will there be twist in the tale?

Bhagyashree S Navare, senior marketing manager at PepsiCo India. Photo: Amit Verma

March 2007. Gurugram.

Bhagyashree S Navare was sipping on her evening tea. A pack of Kurkure lay next to the teapot, along with some assorted cookies. After a hectic week at work, the senior marketing manager at PepsiCo India was looking forward to her chai time, and me-time, on Friday. She opened the pack, took a sip of masala tea, and started munching on Kurkure. Within a minute, though, she paused. A message that hit her mobile inbox said rival ITC had rolled out a couple of snacking labels under Bingo, including a brand called Tedhe Medhe. Come Monday, the marketing executive dropped a message to the entire team: “Pull up your socks. Life is getting real now,” recalls Navare, now associate director and category head of Kurkure and Cheetos.

A year later, life was getting interesting, and challenging, for Joy Chauhan too. The assistant vice president with the then creative agency J Walter Thompson (JWT) in Gurugram had his task cut out: Kurkure—the first homegrown brand of PepsiCo India launched in late 1999—needed a reboot.

Kurkure, which had lorded over the extruded snack market in India for almost a decade, was facing its first tough fight from big boy ITC, which was hyper aggressively pushing Tedhe Medhe across the country. The fledgling challenger had ample tailwinds: Deep pockets and extensive distribution footprint of the parent company ITC, and a strategic launch time targeted to topple a market leader that was probably fighting brand fatigue.

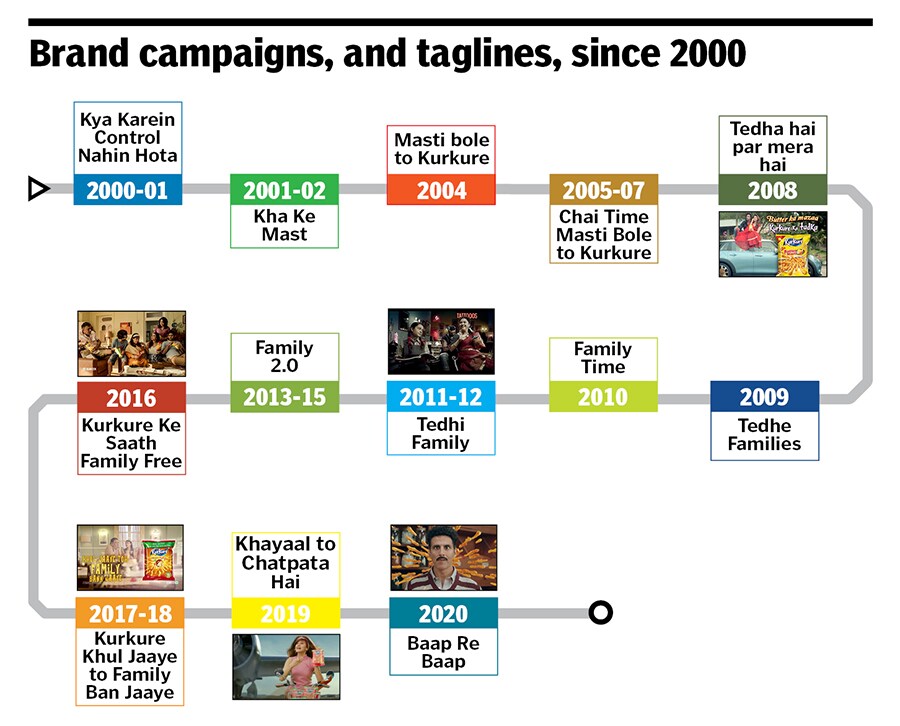

Graphic: Pradeep Belhe; Images: PepsiCo India

The absence of a fitting response from Kurkure was a big challenge, one that Chauhan didn’t take lightly. His creative team brainstormed for over two weeks, but nothing came of it. One afternoon, three members from his core team suddenly went missing from the office. A fuming Chauhan just couldn’t locate them. Early evening, one of them called him. “Tell me your take on this line,” the excited, slightly tipsy voice on the other side of the call asked Chauhan, who froze for a minute. He realised that he had been struggling for this breakthrough for weeks, and it had finally come in a just few seconds.

Chauhan recollects how his voice quivered with excitement as he asked his three colleagues to come back to office immediately. ‘Tedha hai par mera hai’ was what his teammate had told him over the phone. And Chauhan knew it was just what Kurkure needed to take its fight, and positioning, to the next leg of growth.

Using tedha could have backfired as the rival brand Tedhe Medhe already owned the word. But the risk meant little to Chauhan as he was convinced it would work. PepsiCo also came on board, and the Kurkure family survived the first big twist in its story.

Cut to 2020. Over two decades into the journey, Kurkure has not only managed to survive and navigate twists and turns, but it has also grown manifold. For the fiscal ended March 2020, the data for which was filed recently, PepsiCo India saw a dip in beverage revenue, which dragged the overall revenue to Rs5,264 crore compared to Rs6,257 in the previous fiscal. The bright side of the picture was the foods business. “Revenue grew due to strong growth in [the] Kurkure portfolio, Lay’s and Doritos,” the company claimed in its media release this month.

Cut to 2020. Over two decades into the journey, Kurkure has not only managed to survive and navigate twists and turns, but it has also grown manifold. For the fiscal ended March 2020, the data for which was filed recently, PepsiCo India saw a dip in beverage revenue, which dragged the overall revenue to Rs5,264 crore compared to Rs6,257 in the previous fiscal. The bright side of the picture was the foods business. “Revenue grew due to strong growth in [the] Kurkure portfolio, Lay’s and Doritos,” the company claimed in its media release this month.Kurkure, the first homegrown brand of PepsiCo India to clock over Rs1,000 crore in sales a few years back, has grown in size over the years. In its third quarter earnings released early this month, Ramon Laguarta, chairman and CEO of the global foods and beverages major, mentioned “high single-digit growth in India”. Analysts reckon that PepsiCo’s growth in India is largely due to the food portfolio led by Lay’s and Kurkure.

PepsiCo India declined to share the present revenue of Kurkure. Dilen Gandhi, senior director and category head (foods) at PepsiCo India, however, says that playing to its strengths has worked for the brand. “Playing by my rules, I may win sometimes, and may lose sometimes,” Gandhi explains. “But playing by somebody else’s rules, one will definitely lose. We stayed true to the core.”

Navare, who has seen the growth of Kurkure since its birth, explains the core. “There are three pillars of the brand,” she underlines. "The first is delightfully breaking codes; second is staying inclusive; and the last is having a relevant social context for families."

“Put the three together, and you get a brand that has delivered a twist in every tale,” she smiles. A quirky take on Indian families was how the marketing and advertising journey started in 2000, when Kurkure rolled out the first campaign with a tagline ‘kya karein, control nahin hota (can’t control, what to do).’ Though the narrative was built around the ‘power’ the mother-in-law of the house wielded, the humorous depiction made it entertaining for the entire family. The brand managed to break the social code. For the next four years, the focus remained on saas-bahu banter, and in 2004 Kurkure owned the plank of a brand rooted in fun (masti) and family time.

A need was subsequently felt for the brand to occupy a particular time in a family’s day. They zeroed-in on tea-time. The idea was simple: In the early 2000s, more Indian families were becoming nuclear, and even in joint families, the time spent together was shrinking. “Snacks were largely being consumed during tea time,” contends Navare. The brand, she adds, rolled a campaign ‘chai time masti bole to Kurkure.’ Actor Juhi Chawla was roped in as the face of the brand in 2005.

Three years later, the ‘tedha hai par mera hai’ campaign with Chawla in 2008 proved to be a turning point for the brand. It acknowledged and celebrated the idea of imperfection in a family. “The campaign touched an emotional chord with consumers. A popular brand changed into a loved brand,” reckons Ashita Aggarwal, marketing professor at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. “The messaging of “it’s perfect to be imperfect” made the brand sublime,” she adds.

_RSS_Like any family drama, Kurkure faced another twist in the tale in 2008: The plastic controversy. A rumour that the snack contained plastic proved to be an existential crisis. Sales took a beating and consumers turned apprehensive. PepsiCo went into damage control mode: From field trips to plants and countering rumours on social media to talking directly to consumers, the brand did everything it could to manage the crisis. “The plastic controversy,” recalls Gandhi, “made us better and smarter.” The brand started to talk about the ingredients that go into making the product.

The move worked, Chauhan explained, as the consumers got to know the brand more closely. “There are mythical brands that can’t be explained,” says Chauhan, managing partner (Delhi) at Wunderman Thompson. Chyawanprash, he underlines, is one such mythical brand. “Nobody knows what is inside. But the product claims to have been in existence for ages,” he says. By decoding what is inside the product, Kurkure had the advantage of not being such a brand, thereby earning back its place in Indian households

After the plastic twist, came the challenge of various lookalikes: Chutkure, Hurhure, Kurkare, Karkare... At one point, around 2013, there were hundreds of them. The problem, Gandhi recalls, was not with competition, which is always good for business. “The fight was not legitimate. They were either blatant copycats or fakes,” he says. Apart from legal recourse to fight fakes, the brand rolled out a campaign to educate consumers. With “Kuch bhi crunchy milega toh khaoge kya? (Will you eat anything that is crunchy?), the brand exhorted consumers to buy their Rs5 pack, which was introduced to fight low-priced local brands that had flooded the segment because of the low entry barrier.

After the plastic twist, came the challenge of various lookalikes: Chutkure, Hurhure, Kurkare, Karkare... At one point, around 2013, there were hundreds of them. The problem, Gandhi recalls, was not with competition, which is always good for business. “The fight was not legitimate. They were either blatant copycats or fakes,” he says. Apart from legal recourse to fight fakes, the brand rolled out a campaign to educate consumers. With “Kuch bhi crunchy milega toh khaoge kya? (Will you eat anything that is crunchy?), the brand exhorted consumers to buy their Rs5 pack, which was introduced to fight low-priced local brands that had flooded the segment because of the low entry barrier.The category leader also had to fight against local genuine rivals who were lured into the category because of the massive success of Kurkure: An estimated 3,000 brands sprung up between 2009 and 2012. The fight was also coming from regional players with heft such as Balaji Foods, Yellow Diamond, DFM Foods, Haldiram's and Bikanerwala. Not to forget ITC’s Tedhe Medhe.

PepsiCo India stepped on the innovation pedal to fight the challengers. “They rolled out savoury flavours and gave it a pan-India appeal through regionalisation and localisation,” says KS Narayanan, a food and beverage expert. What came next, and continues still now, is a battery of flavours for different parts of the country: While masala munch, chilli chatka, green chutney style and puffcorn became bestsellers in North India, the South got hooked to naughty tomato and Hyderabadi hungama.

The fight, though, took a toll on Kurkure, which reportedly slipped from its dominating position of over 50 percent value market share in 2014 to 28 percent by March ended 2019. Analysts, citing Nielsen numbers, say the brand has clawed back to mid-30s in value market share. Close on the heels, though, is Tedhe Medhe, which is over 20 percent, explain analysts requesting anonymity.

Back in Gurugram, Navare is not worried. The mantra that has worked out for the brand, she points out, will continue to work: Focussing on one’s strengths. “We are good at our game, we will keep winning,” she says, munching on another piece of savoury snack from the Kurkure pack. The crunch is still intact.